How do first home buyers afford anything?

Of all the narratives that exist within the realm of Australian housing and economics, one of the most hotly debated is “If housing is so expensive, how are people buying into the market?”

Today, we’re going to take a data-driven deep dive into how Australians continue to enter the housing market for the first time.

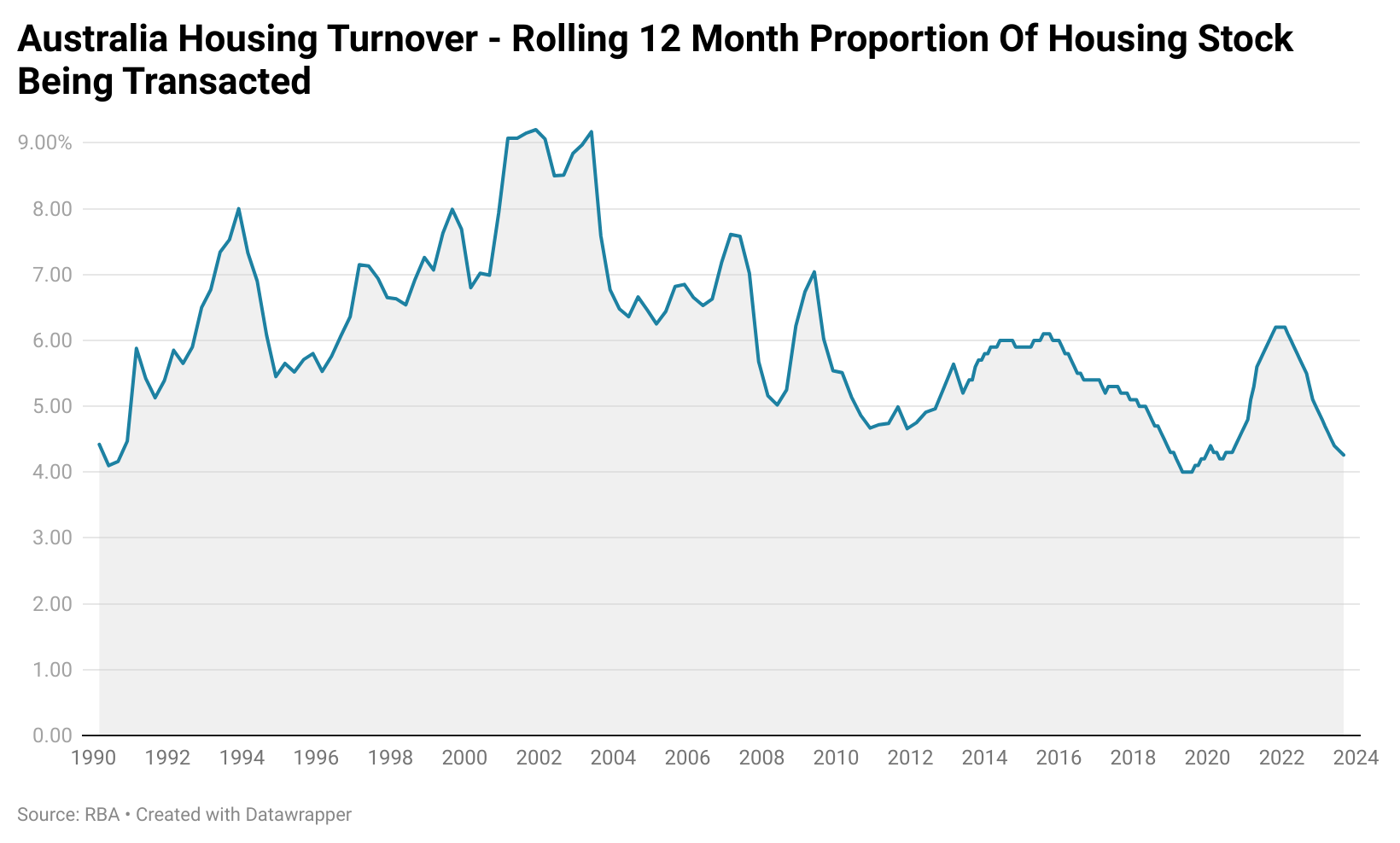

Part of the puzzle is that people aren’t buying homes in the numbers they did in decades past.

Today, the national housing turnover rate is approximately 4.6%, compared to a peak of 9.1% recorded in 2001. The current figure has more in common with the rate of housing turnover seen following the 1990 recession than with more normal conditions. Given that this era held the highest level of Australian unemployment since the Great Depression, it serves to illustrate how badly normal housing market conditions have been damaged by significantly higher prices.

Due to the much higher cost of property relative to incomes now compared with the era of peak transactions, it’s perhaps unsurprising that transaction volumes have fallen so dramatically.

A Relative Handful

A Relative Handful

In previous generations, embarking on the journey of home ownership was done as a single person or as part of a couple, with only a relative few doing so with the support of parents, other family members or friends.

Today could scarcely be more different, with those purchasing with some form of assistance now in the majority.

“If we assume the majority are first-home buyers, it would imply about 75 per cent of first-home buyers were receiving some form of family assistance,”

-Jarden Australia Chief Economist Carlos Cacho

According to investment and advisory group Jarden Australia, 15 per cent of borrowers are receiving an average of $92,000 from parents.

This is an enormous jump from the average level of support on offer in 2010. According to figures from research firm Digital Finance Analytics, in 2010 the average level of assistance from the Bank of Mum and Dad was $23,500, with only 6% of first-time home buyers receiving help.

It’s Albo’s Housing Market

At the recent federal election, the Albanese government took a policy that would effectively allow most first home buyers a government-backed loan with just a 5% deposit.

This marks the major expansion of the existing schemes, first implemented by the Morrison government and later expanded under the current government.

Government organisation Housing Australia provides the mechanism for banks to write government-backed mortgages for first home buyers with as little as a 2% to 5% deposit, depending on a household’s circumstances.

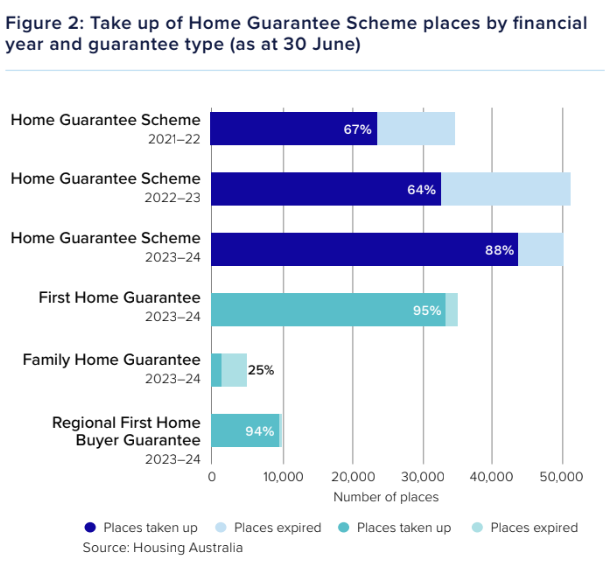

It was introduced in October 2019 by the Morrison government, providing 10,000 places annually.

Over time, the scheme has grown larger and larger, with the First Home Guarantee providing 35,000 places in 2023-24 and the Regional First Home Guarantee providing a further 10,000 places.

According to the most recent figures from Housing Australia, over 1 in 3 first home buyers who purchased a home in the last 12 months did so with support from one of its programs. Notably, this is down from almost 40% in the previous year’s figures.

The Takeaway

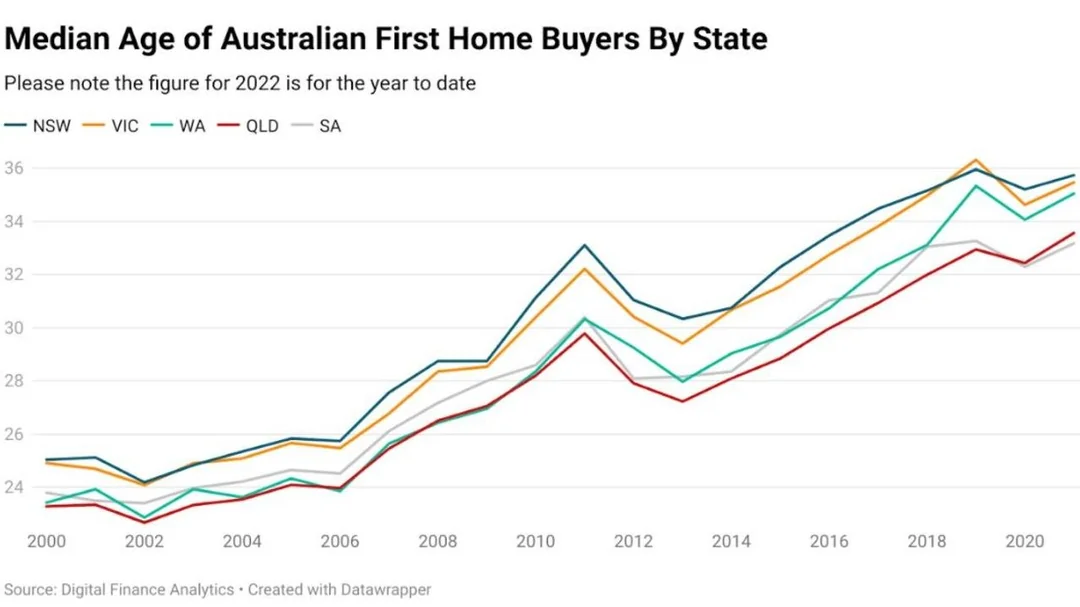

Despite the median first home buyer getting older and older over time, the proportion of first home buyers getting into the market organically without some form of parental or government assistance continues to dwindle.

With the Albanese government set to drive that proportion even higher with its government-backed mortgage scheme and its shared equity program, the future of Australian homeownership appears to be one that will be increasingly defined not by how hard one has worked, but by to what degree one has help from the government or family.

In a vacuum, government and parental assistance are not bad things. Preferential access to loans for first home buyers helped to work wonders on the nation’s home ownership for over a decade in post-war Australia.

But in a market where it’s just the source of more petrol to pour on an already roaring fire, which is heavily fuelled by high levels of migration and far higher than historic levels of investor demand, it’s likely to simply boost housing prices higher, leaving even more people reliant on assistance to achieve a home of their own.