The housing crisis persists in a significant portion of the nation, and neither the Albanese government nor state governments appear to be making the necessary policy changes to tackle the housing deficit effectively.

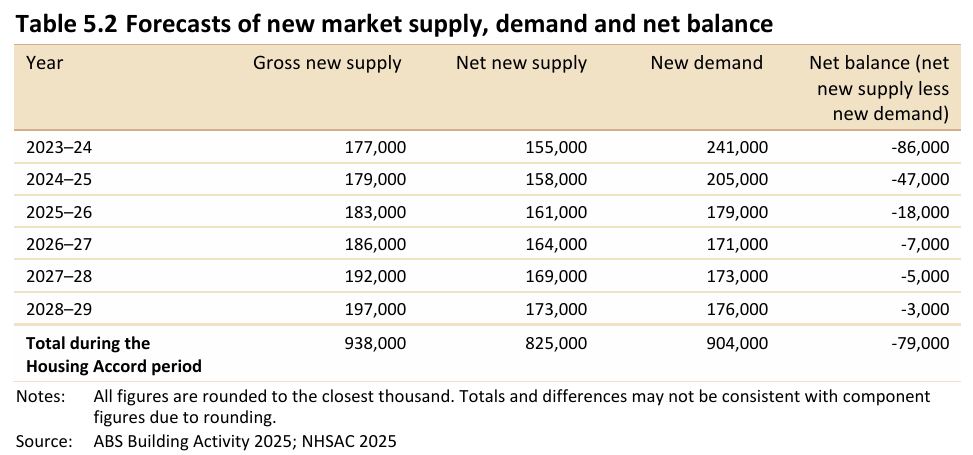

According to figures from the Albanese government’s National Housing Supply and Affordability Council (NHSAC), the housing deficit is projected to increase annually until at least 2029, marking the end of the forecast period.

However, there is more to it than simply dividing the level of population growth by the size of the average household.

Changes in how existing individuals and households choose to live or redevelop homes also need to be considered.

According to figures from the Housing Industry Association (HIA), between 100,000 and 120,000 new homes will be required, assuming zero population growth, average economic conditions, wealth creation, and demographics consistent with long-term averages.

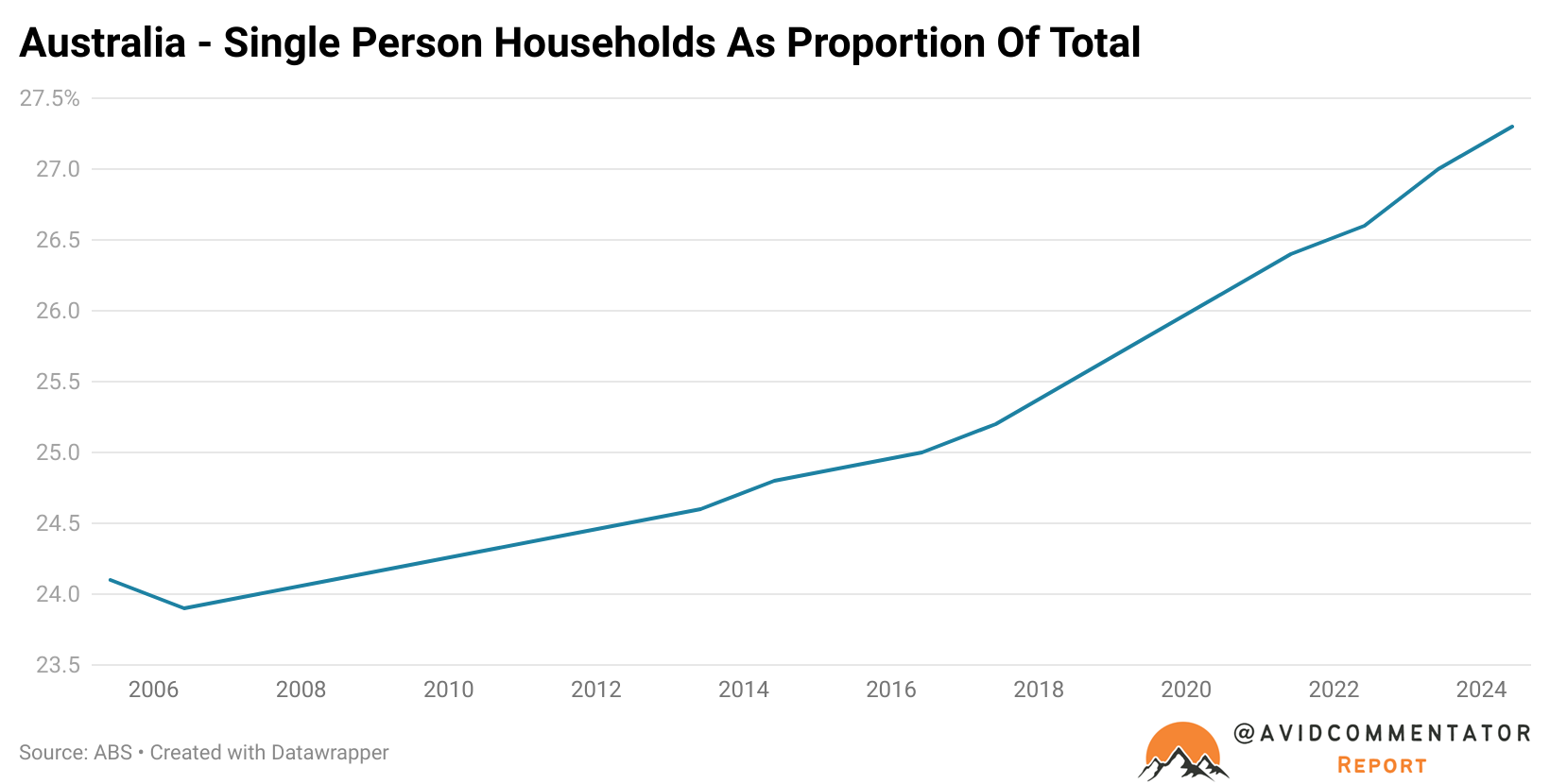

One of the best illustrations of this is the proportion of occupied homes that are inhabited by single-person households.

Since the start of the annual collection of data on this metric, it has risen from 24.1% of households in 2005 to 27.3% in 2024.

If we were able to magically reduce this figure back to its 2005 level and integrate these individuals into households at the average rate of occupancy by adults, it would result in a reduction of total demand for homes by over 174,000.

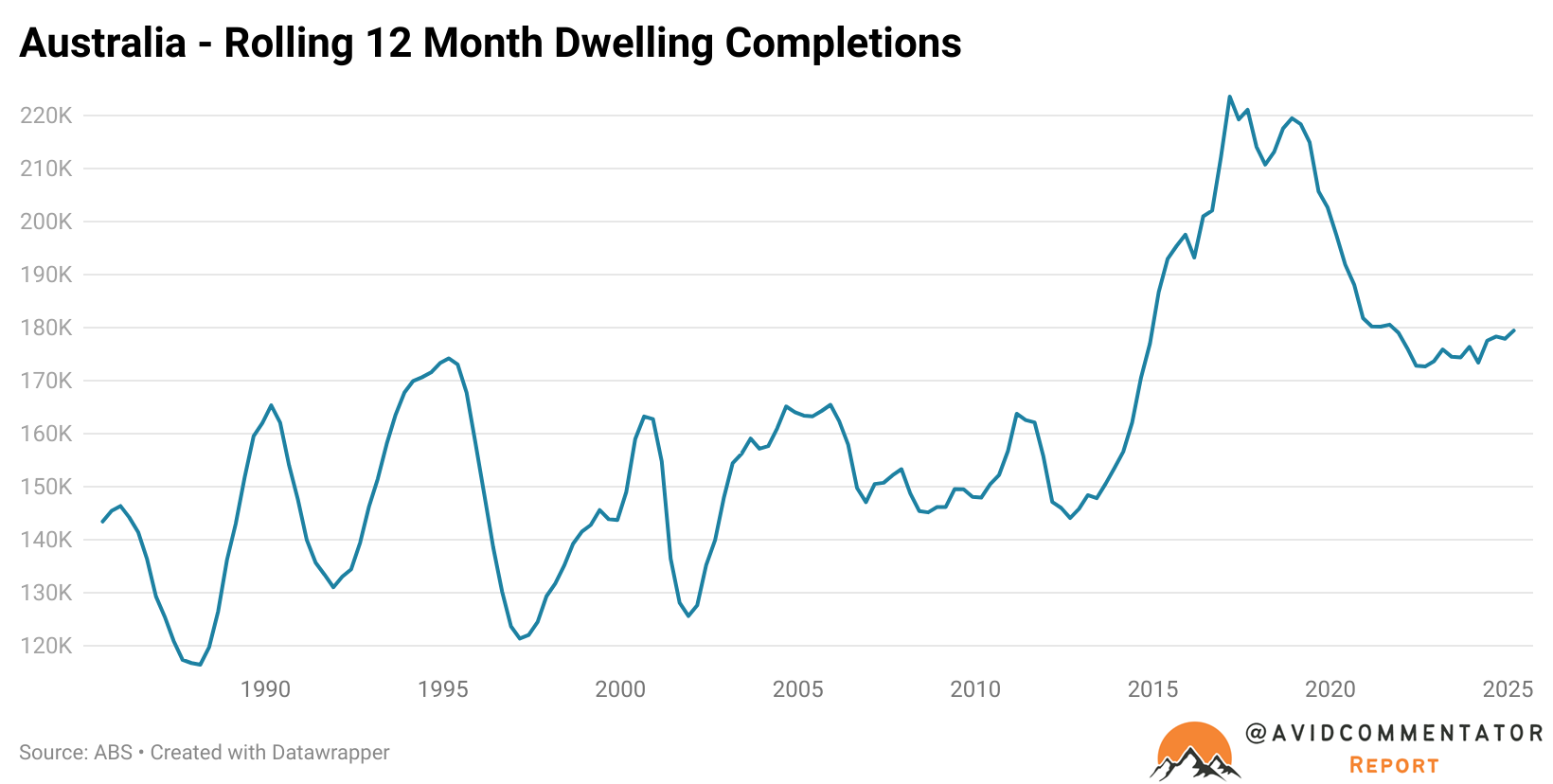

This is roughly in line with the total number of dwelling completions observed over the last 12 months of data from the ABS.

However, given that somewhere between 10% and 15% of dwelling completions do not contribute to housing supply in net terms due to demolitions, the impact of this demand reduction would be even more significant than the headline number suggests.

These developments are ironic when considered in light of high levels of migration and the broader pro-migration narrative.

As the population ages and the existing population demands significantly more homes, policymakers should pause to consider the impact of these ongoing demographic shifts before deciding on the right level of migration for Australia.

It would be easy for an observer to conclude that the overwhelming majority of Australians have a roof over their heads; therefore, whatever housing shortage exists is mild.

But this is not about securing the latest and greatest toy for your kids or a sought-after gift for a partner; it’s about an absolutely foundational element of the hierarchy of needs: shelter.

People can and do make whatever compromises are necessary to keep a roof over their heads, which can, at the extreme, involve living in conditions not fit for human habitation or staying in a home where they feel or are demonstrably unsafe.

Ultimately, the failings of policymakers at all levels will continue to echo throughout Australian society for decades to come, whether it be in the form of the housing deficit, the economic drag from high housing costs, or the deep social costs that come from forcing people to live in homes they desperately need not be in.