Chinese success will smash the Aussie economy

At the recent World Economic Forum’s (WEF) annual meeting at Tianjin, China, Chinese Premier Li Qiang pledged that China will become a “consumption powerhouse” capable of fuelling domestic and global growth.

“This will make China a mega-sized consumption powerhouse, on top of being a manufacturing powerhouse,” Li said

“We are on track to become a high-income country supported by robust consumption upgrades,” he added.

This narrative being talked up by the Chinese government is nothing new, they have been talking about the transformation of it’s industrial and construction focused economy to one more focused on consumer consumption and services for over two decades.

So far their level of success in achieving this goal is somewhere between minimal and non-existent depending on your chosen metric.

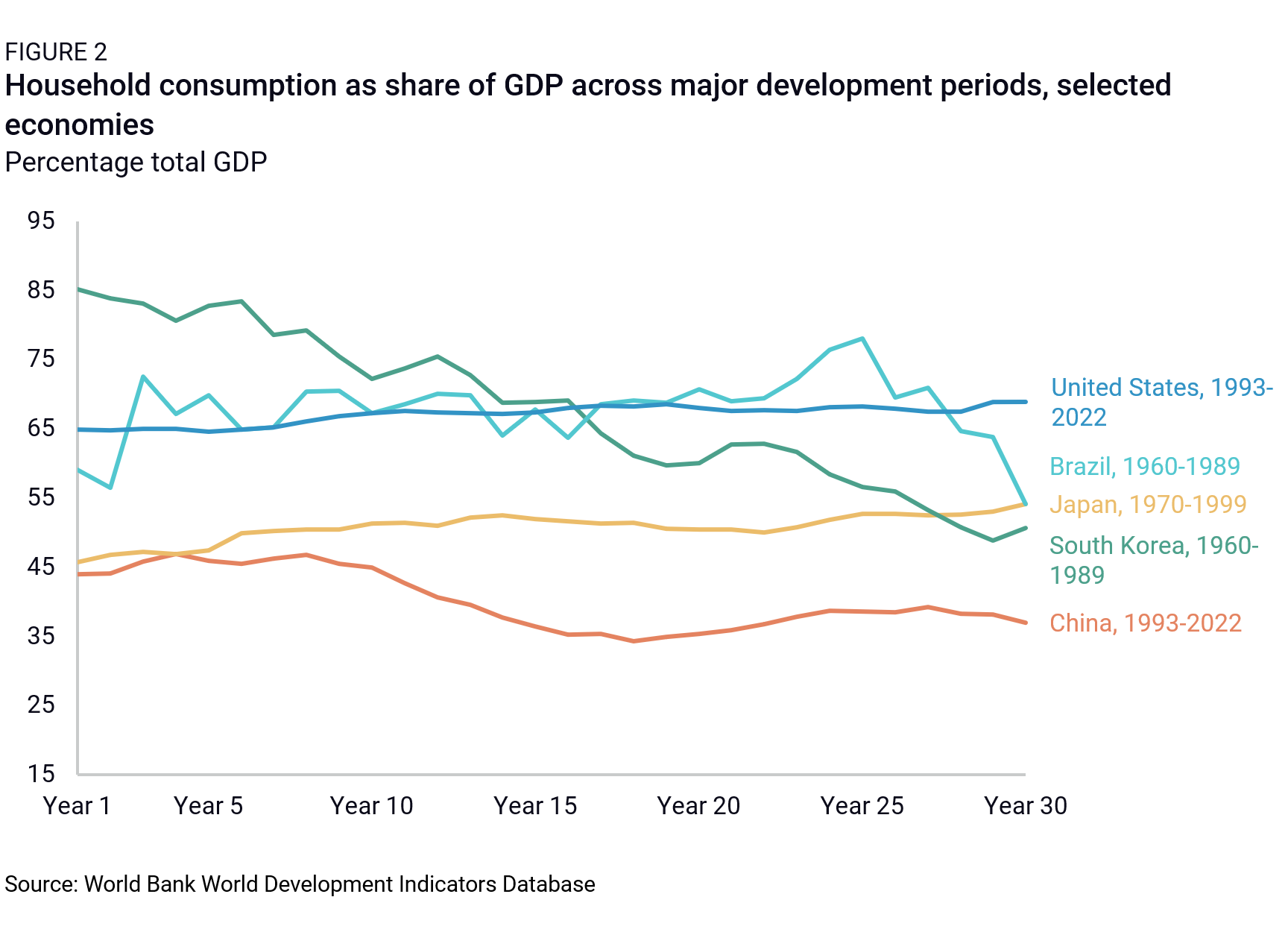

Overall, the household consumption share of GDP is not far from all-time lows and is significantly below other industrialised economies at the same stage in their development.

Source: Rhodium Group

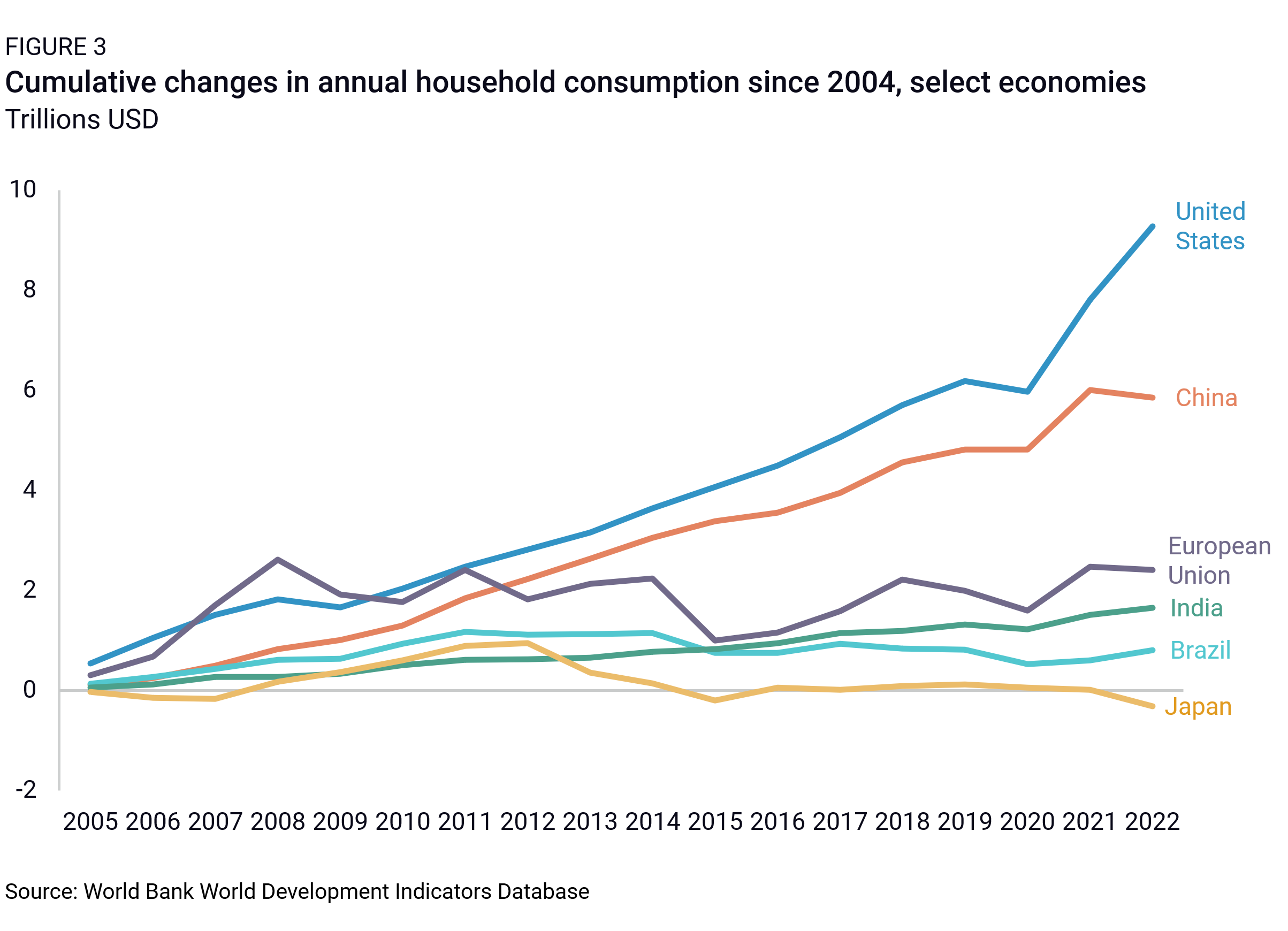

This is not to say that Chinese household consumption is not growing; it most certainly is, but it’s not growing significantly faster than other parts of the economy, which is necessary to begin the shift toward a more consumer- and services-focused economy.

Source: Rhodium Group

Part of the issue is that Chinese households are absolutely prolific savers and investors of their incomes, with household savings consuming 31.7% of net income in aggregate terms in 2023. This is almost six times higher than the rate of household savings seen in Australia.

While it’s beneficial for Chinese households in aggregate to have this enormous war chest of capital, it inevitably contributes to the share of GDP as a proportion of household income staying significantly lower than in other industrialised economies.

But what if that were to change and the Chinese economy genuinely committed to pursuing the long and challenging path to becoming a consumer economy? This could be driven by several different motives, from the desire for a more self-sufficient economy less reliant on external demand to by necessity, as industrial overcapacity, rising trade barriers, and a slowing global economy all begin to bite.

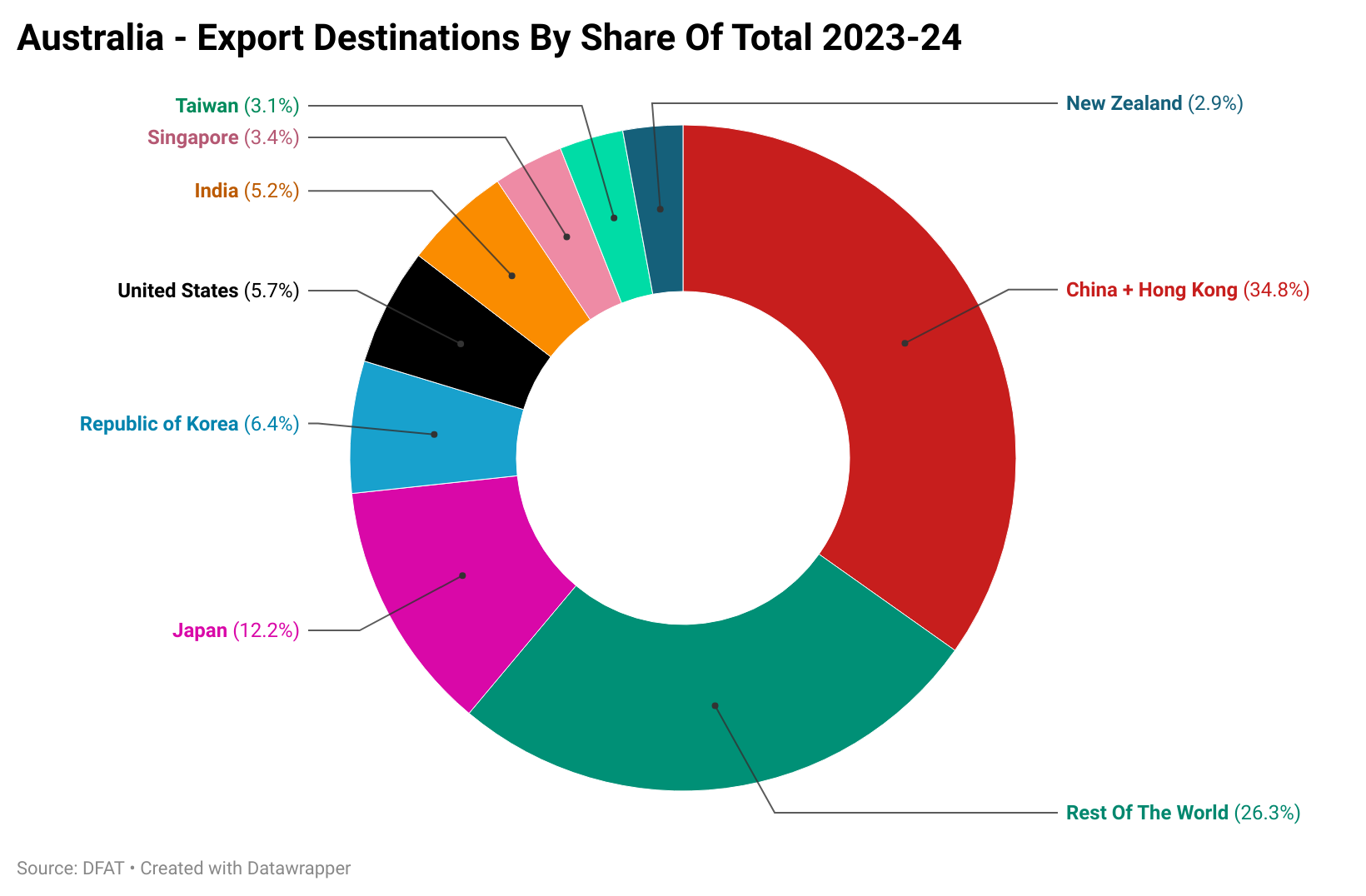

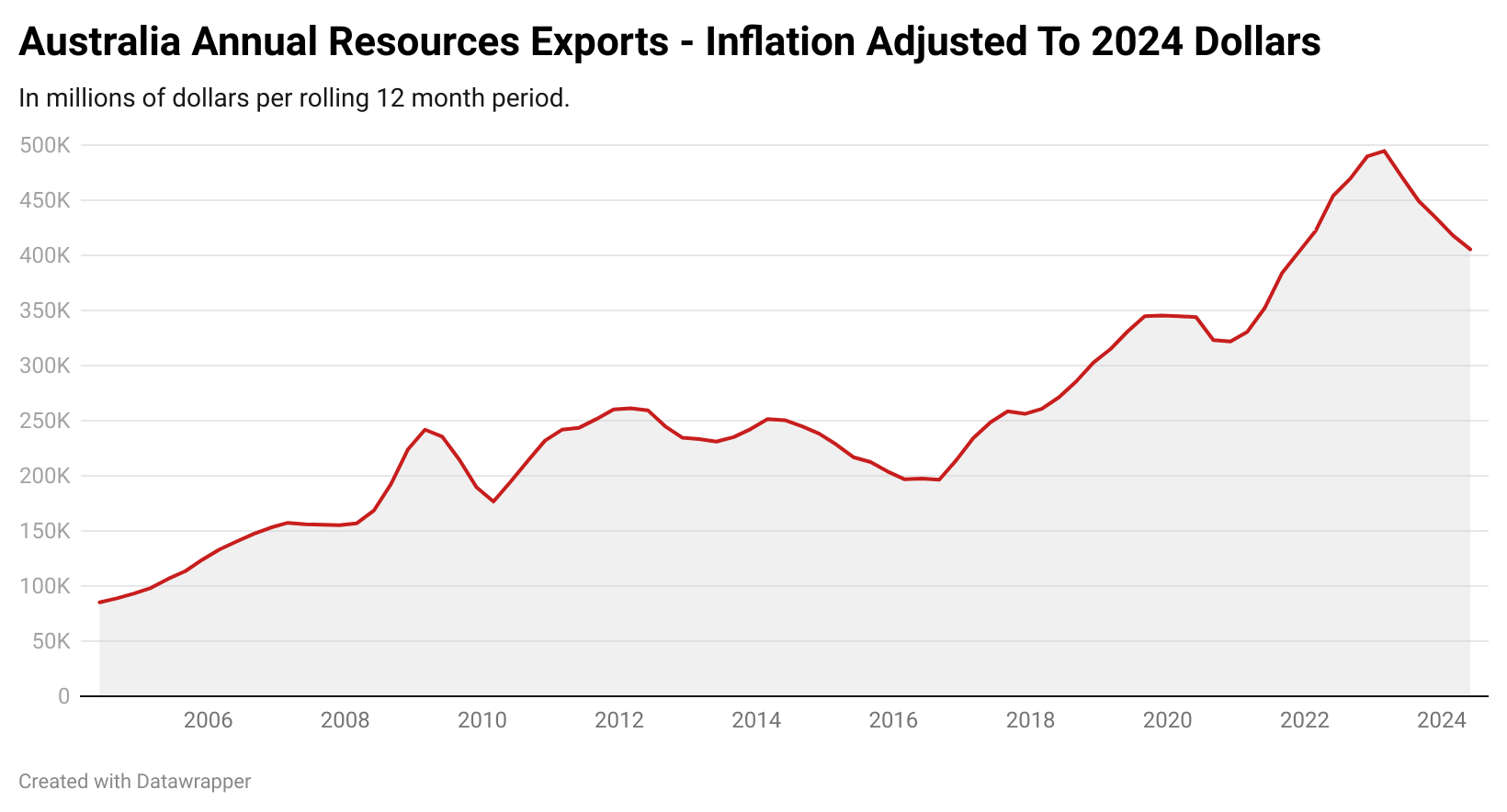

Australia is often seen as a proxy for exposure to the Chinese economy, with the success of China’s industrial and construction-focused economy being Australia’s success, at least for the coffers of the state and federal Treasuries.

But if Chinese government policy were to shift much of its focus and its resources away from the construction and manufacturing sectors and towards domestic consumption, that could leave Australia in a remarkably challenging position.

We have arguably already seen a microcosm of this sort of shift in the various subsidies provided to households to purchase appliances or vehicles to drive an expansion of domestic demand.

If the Chinese government did move to create a sustained and ongoing shift toward a consumer economy via structural income transfers from SOEs to households, lower reliance on infrastructure and construction spending would shrink the need for resources on the proverbial roads to nowhere.

That would leave Australia’s heavily China-focused commodity exports in an extremely challenging position, with no other nation in the world, even combined, able to replace the level of demand a dramatic shift in the nature of the Chinese economy would create.

Australian policymakers have long said their prayers at the altar of Chinese prosperity, hoping that the demand for commodities would last as long as the mythos contained within the narrative of the ‘Asian Century’.

Ultimately, they should be careful what they wish for, because if one day China’s government gets the type of prosperity it truly wants, it will be a net hit to Australia’s economy, not a help.