When the Reserve Bank Governor Philip Lowe first began raising interest rates in May 2022, the question in the minds of many commentators and economists was, when will they be cut again?

What followed was the largest and swiftest relative rise in interest rates in Australia’s history.

But then the Reserve Bank did something that only a handful of people were expecting: they kept rates higher for longer than almost any other major monetary policy cycle since records began in 1959.

Fast forward to February 2025, and rates were finally cut by 0.25%, followed by a further 0.25% cut in May.

The consensus was it was full steam ahead for rate cuts from here, with near certainty in the media and among commentators that rates would be cut in July.

Property portal Domain was so certain of a rate cut that a post was made on its Facebook page noting: “With property prices forecast to accelerate” and a graphic that the RBA had indeed cut rates by 0.25%.

It was not to be.

The RBA Board, by a result of 6 to 3, voted to hold rates where they were, to wait and see how inflation performed in the second quarter CPI print.

Despite it being fairly regularly talked up by some when it produced a favourable result, Bullock also noted that the Monthly CPI is too volatile and not necessarily reflective of what’s going on.

Which leads us to the big question of the day: what factors could have contributed to Bullock and the rest of the RBA voting to keep rates where they are?

Much of it comes down to what I like to call ‘Burnout Economics’, which is a term I coined back in 2021.

In short, it describes a situation where a central bank like the RBA has its foot on the brake, attempting to control inflation, but at the same time, fiscal policymakers have their foot mashed hard on the accelerator.

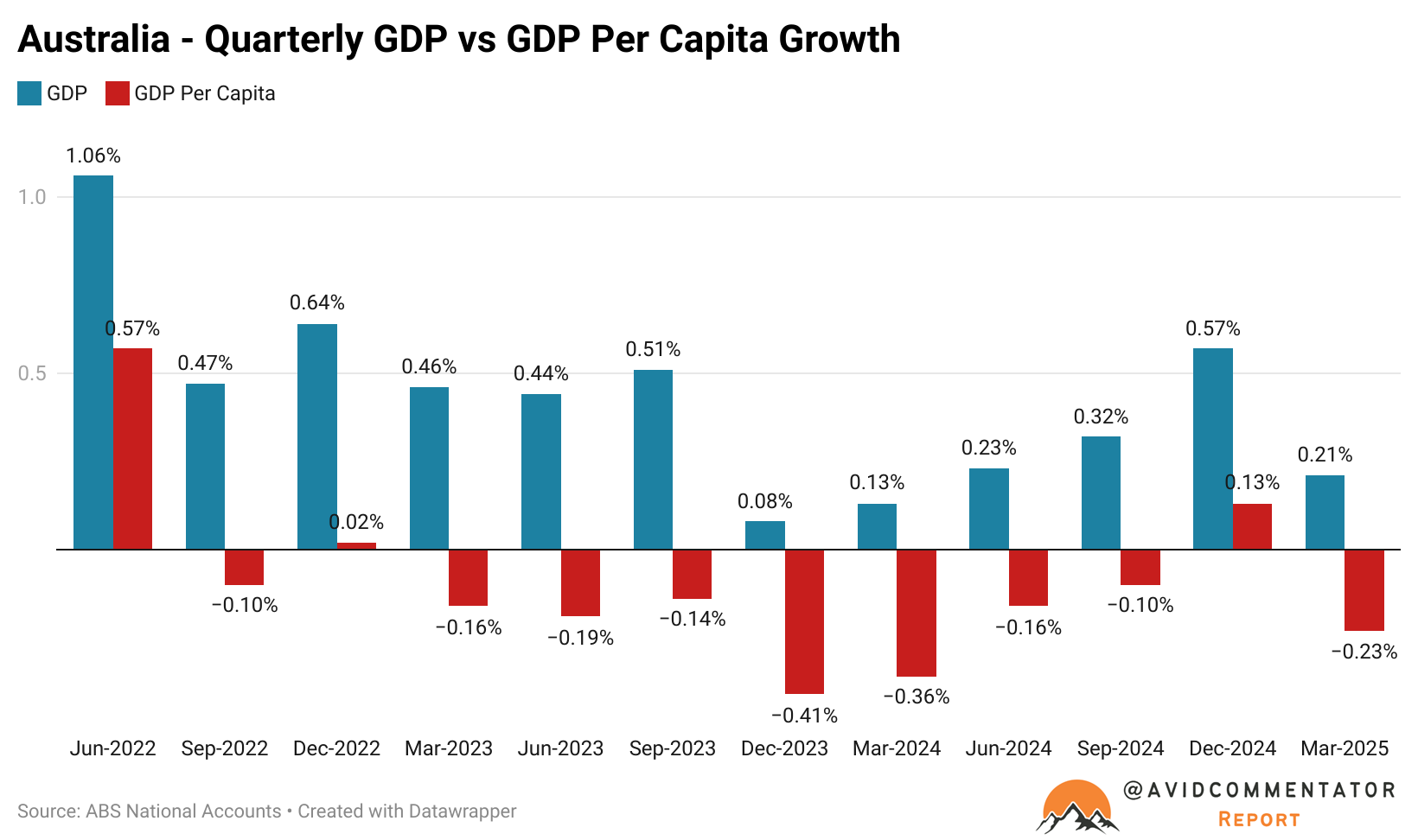

The net result: a whole lot of smoke, a whole lot of noise, and not a lot of forward momentum.

Which pretty much describes the current state of the Australian economy.

The ironic thing is that actions of various levels of government to support the economy and the labour market have resulted in a set of circumstances where the path forward for interest rates is much less certain than it otherwise would have been.

If the economy had dipped more seriously into contraction due to lower migration or if there was slightly higher unemployment due to less non-market job creation, then yesterday’s rate meeting would have been a lock for a cut, and there probably would have been more cuts prior.

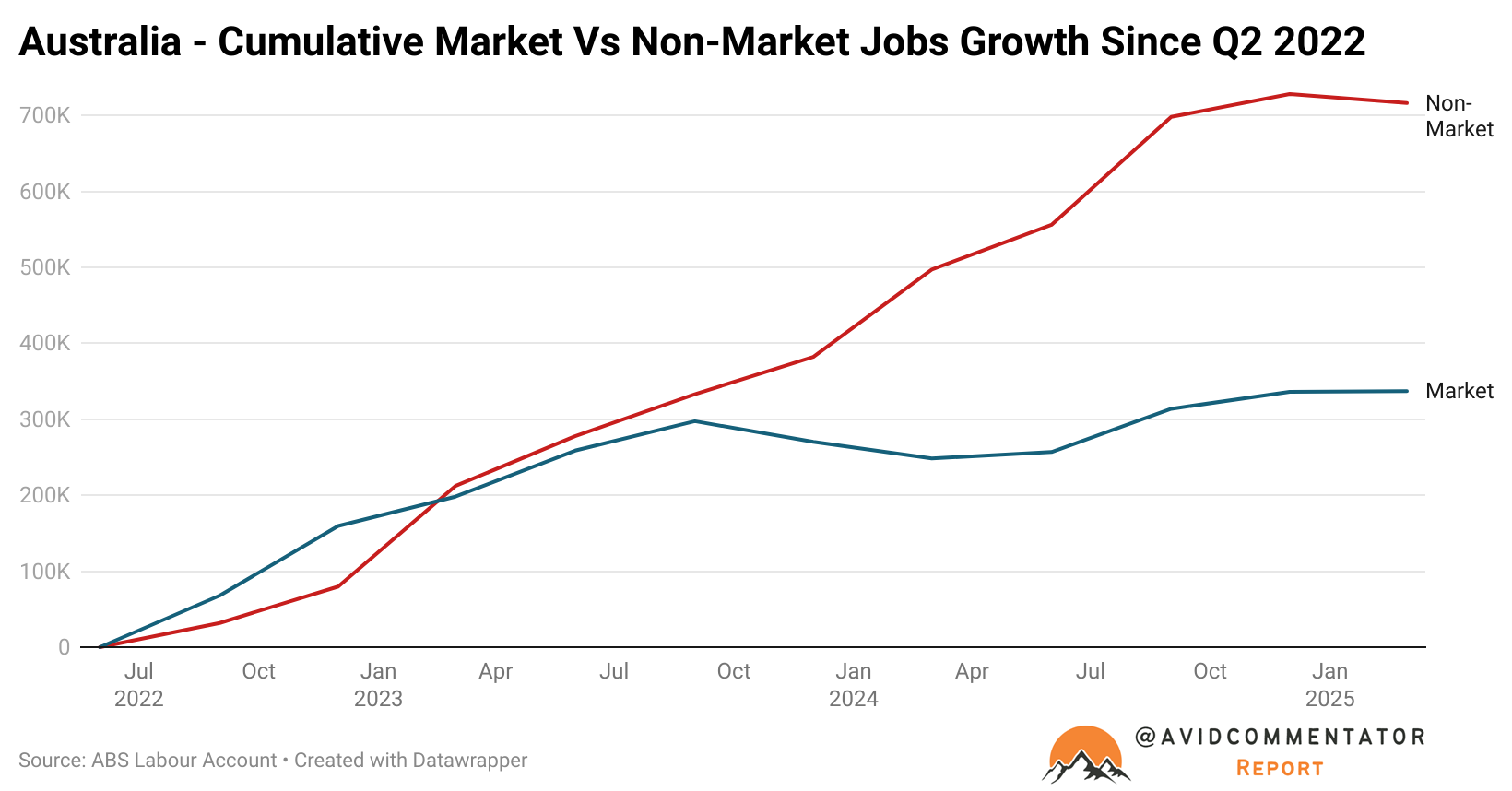

In reality, job creation in generally taxpayer-funded industries has taken the wheel and is now driving the overwhelming majority of employment growth since late 2023.

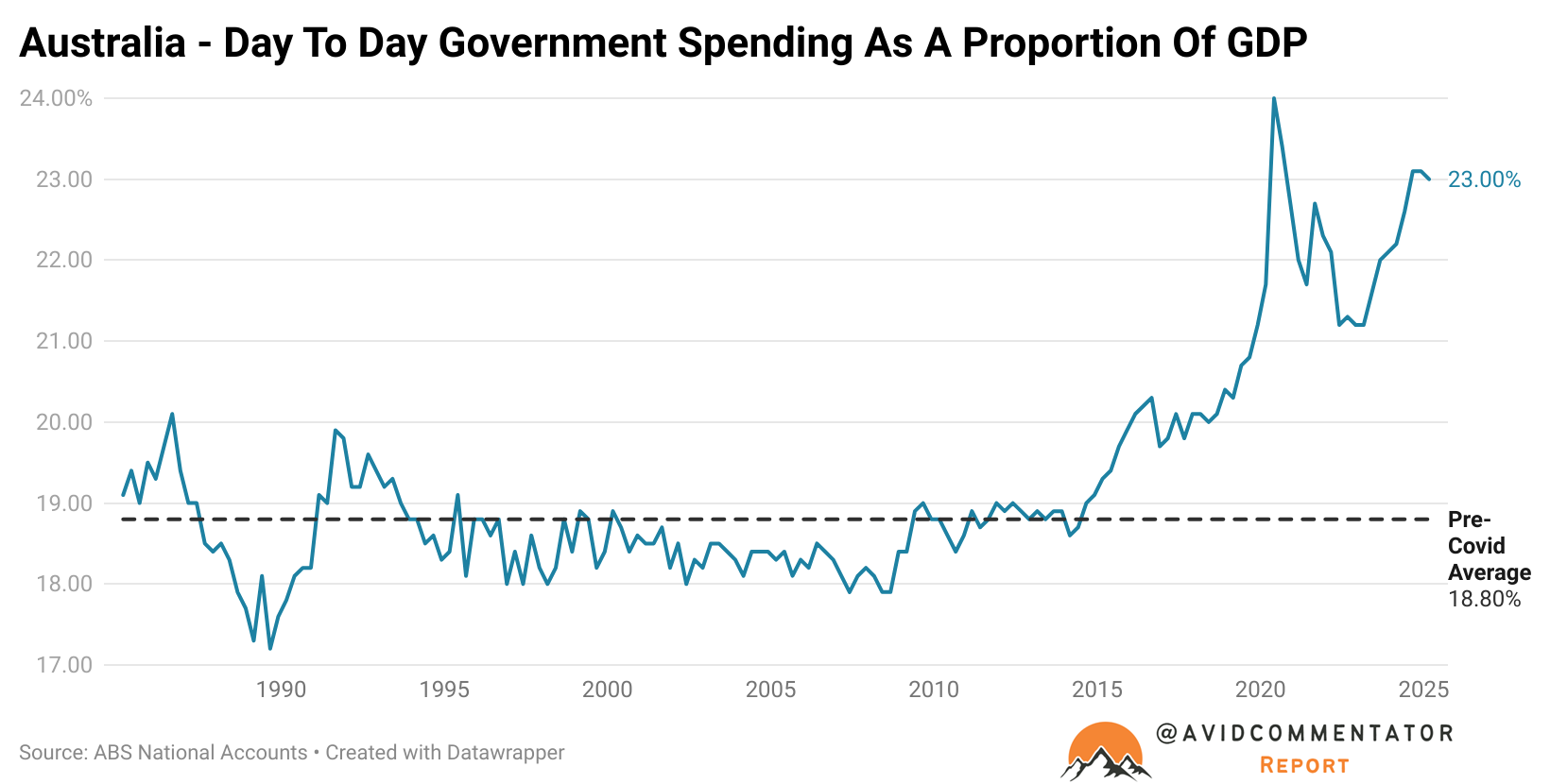

Meanwhile, the total level of economic activity resulting directly from day to day government government is near all-time highs and far above what is normal for the Australian economy.

In a lot of ways, the recent journey of interest rates has been more of the making of the government than the RBA. Despite the fact that it has kept inflation higher than it otherwise would have been, the Albanese government has pursued a strategy of attempting to mitigate the impact of tighter monetary policy on the economy.

While Burnout Economics has serious costs, whether they be to living standards or government coffers, we appear to live in a nation where the government will attempt to avoid economic downside at an aggregate level and, by extension, threats to the housing market, despite those costs.