On Monday, former Realestate.com.au Director of Economic Research and now independent property analyst Cameron Kusher posted on X (Twitter) that in his view the family home should be included in the pension assets test and that rather than older demographics being provided with additional incentives to downsize, “it’s time for the sticks rather than carrots”.

The tweet prompted a wide range of responses, from strong levels of support to heavy opposition.

Kusher went on to say:

“Lots of comments on this post with plenty in support and the older cohort dead against it. I would be willing to accept removing stamp duty on all transactions and replacing it with an ongoing land value tax to help enable downsizing.”

Removing stamp duty in favour of a broad-based land tax is an increasingly popular idea, but it’s not without its issues.

To put the potential risks into perspective, a little story time.

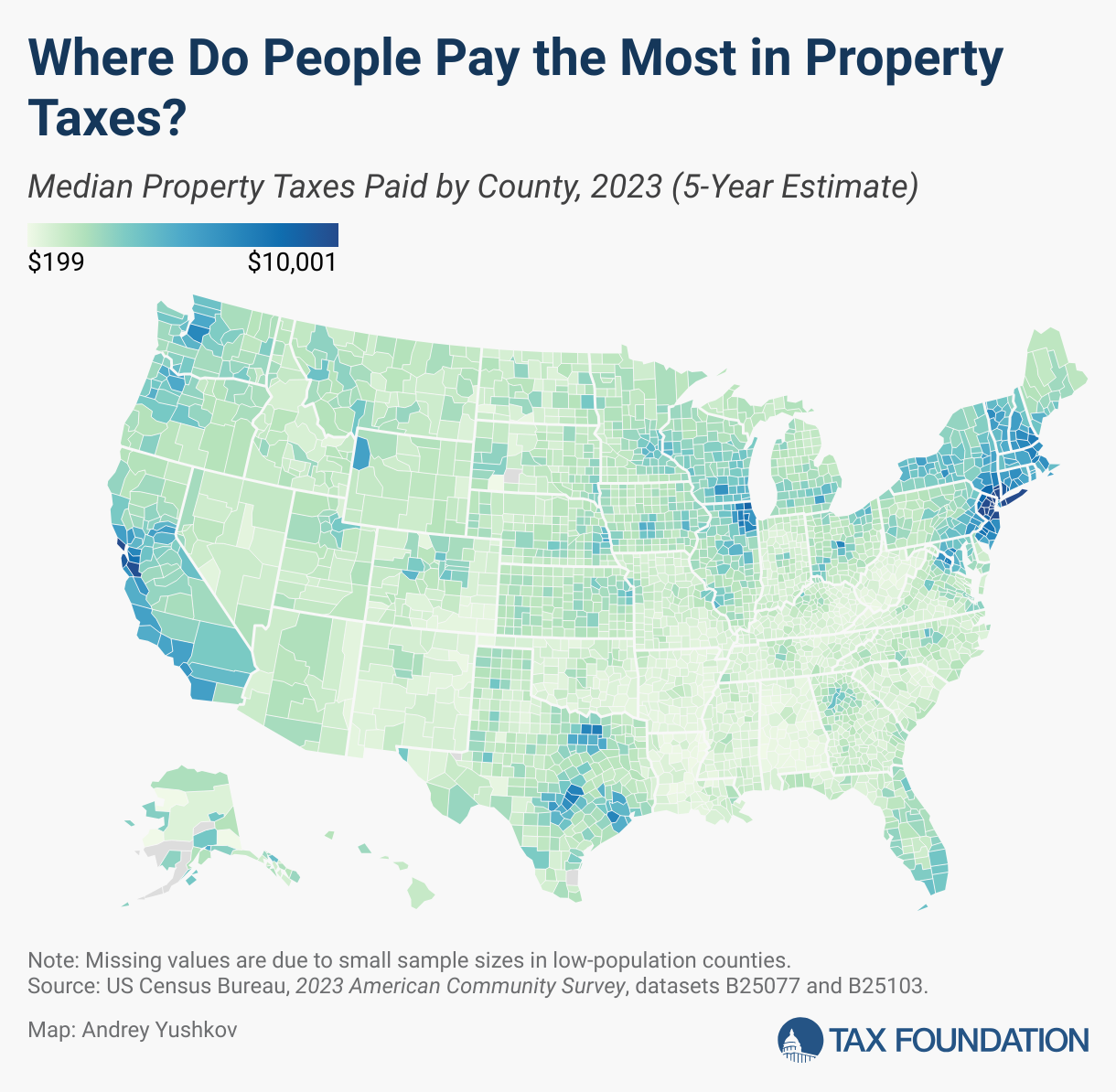

A family friend is a retired health worker in Rochester, New York (about 1.5 hours East of Niagara Falls), she lives in a normal home, which is a bit above the average for the area but still less than half the national median. Their property taxes are over $7,000 USD per year.

At the median nationally, Realtor.com puts the average annual property tax at $3,500 USD per year.

The disparity is largely due to the challenging budgetary environment facing New York counties and the state more broadly, which holds significantly more debt than the average.

Playing The Reverse Card

For the longest time, rising property prices have been a celebrated part of Australian life, but if a land tax were to be applied like in the United States and elsewhere, it would mean that rising property prices would mean rising taxes.

Meanwhile, for retirees, a scenario in which stamp duty was no longer a factor would, in theory, give them greater options to downsize, but it would also mean a sizable tax bill each year.

In the U.S., the average rate of annual property taxes consumes approximately 14.6% of the average annual Social Security payment for retired workers.

For people in states and/or counties with less than stellar fiscal management skills, it can rise to consume well over 1/3 of an individual’s social security payment.

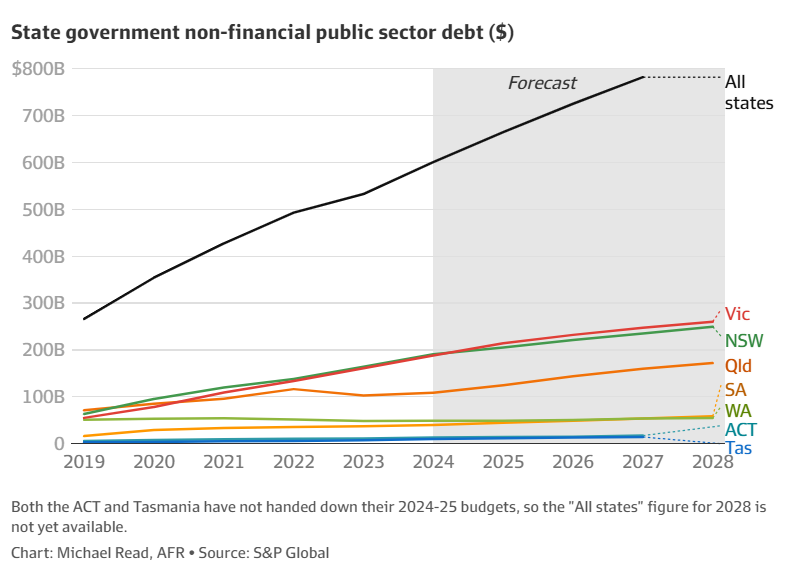

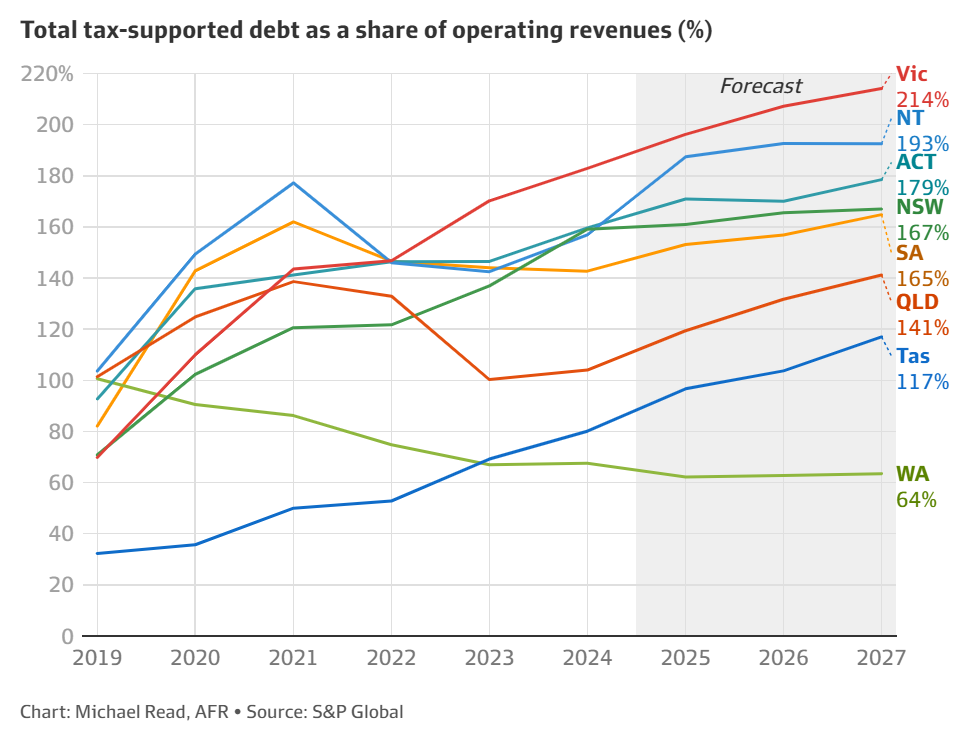

With debt loads rising rapidly in several Australian states and state governments increasingly looking to find increased revenues, it’s not hard to imagine a state in fiscal difficulty using land taxes to attempt to repair their budget position, in much the same way as has occurred in New York and other U.S states.

Kusher is correct that the status quo is untenable, but I suspect that even if the political will were there to make a change, the level of downsizing is unlikely to see a major increase. He goes on to rightly note:

You’re also going to have to find a way to increase density in a lot of areas to give downzisers some more options to move to as they shift from family homes.

Given the cost of townhouses and apartments desirable for downsizers accustomed to a spacious family home, it’s unlikely the nation will see a shift toward significantly more prevalent downsizing.

Ultimately, it comes down to demand for family homes, and they certainly don’t grow on trees. As younger demographics have families and older demographics overwhelmingly stay put, the level of migration needs to be heavily considered in this context.

There are only so many family homes and fewer still in deeply desirable areas. If the current status quo continues, demand for these homes will continue to outstrip supply, with consequences for our society and our economy that will echo for decades to come.