Australian freedom is under attack

When the word freedom comes to mind in our collective consciousness, it can be interpreted in a number of different ways. It can be an expression of one’s ability to share their ideas or views freely, or it can relate to one’s capability to go about one’s day unimpeded by a Draconian state.

But there is another definition of freedom, one that is especially relevant in present-day Australia, that impacts the overwhelming majority of us in some capacity: the ability to live our lives the way we choose if we work hard enough.

Once upon a time, a single average full-time wage was enough to buy a house and support a family, with any additional income in the form of a second earner being a significant boon and a second full-time earner offering a huge leg up to living standards versus other households.

In present-day Australia, a second earner is now all but a requirement for a household on a single average full-time wage to buy a house.

This shift is summed up quite nicely by marketing expert Rory Sutherland:

The creation of the double inome household was one of those changes which went from being an option to an obligation. The principal beneficiaries were government who could had twice as many people to tax. Property owners because now you needed two salaries to buy a house….And the unit of the household, the family, lost 35 hours of discretionary leisure every week with no commensurate increase in living standards because the money got soaked up by property prices and by taxation.

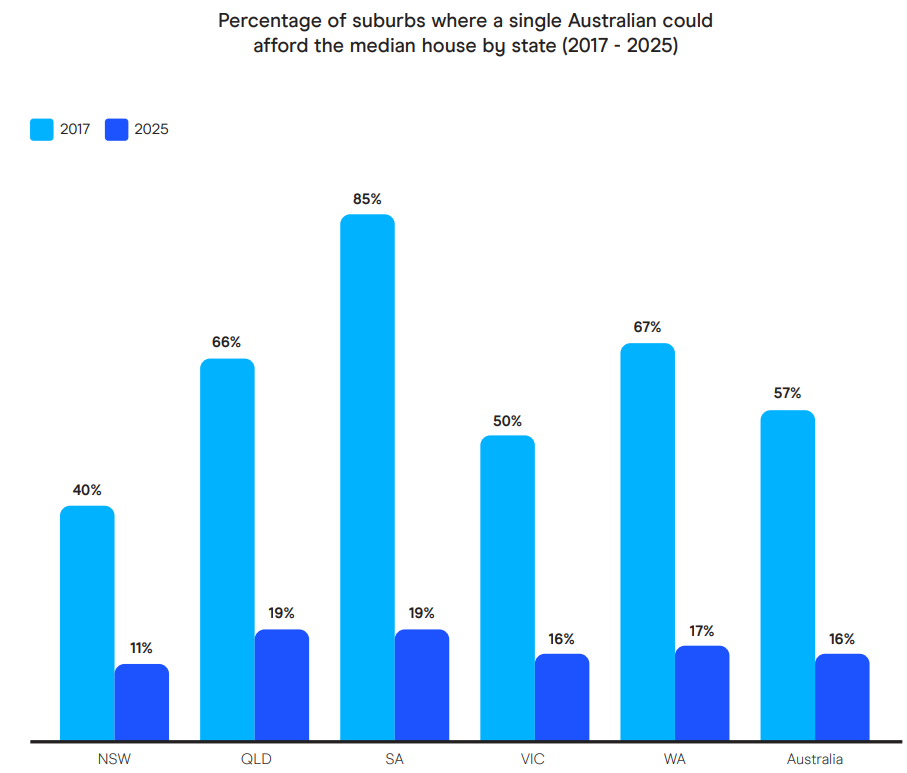

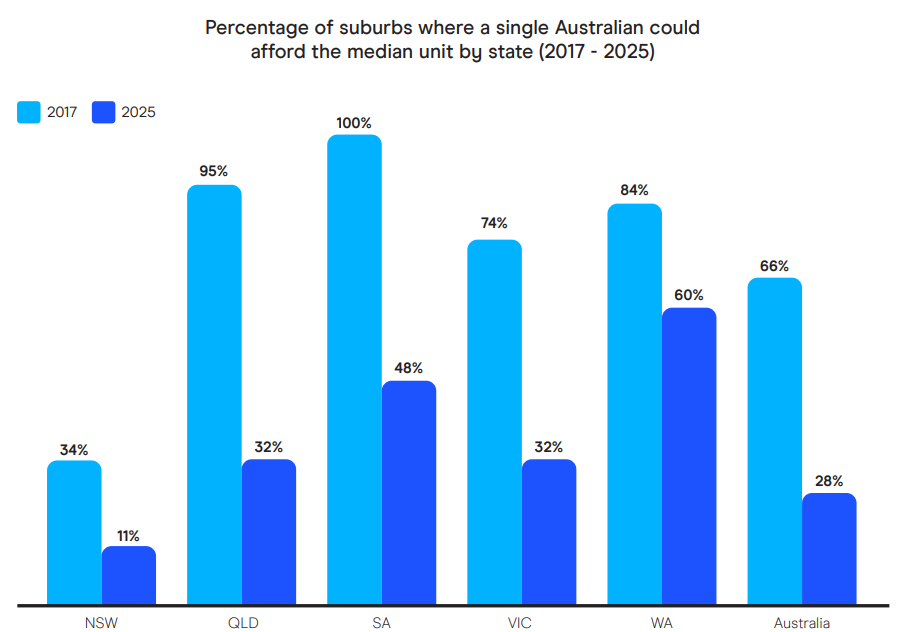

According to figures from Finder.com.au First Home Buyer Report, a single person attempting to buy the median house can only do so in 16% of suburbs Australia-wide. If the focus is shifted from houses to units, things do improve, but not by as much as one might think, with only 28% of suburbs Australia-wide being affordable.

Source: Finder First Home Buyer Report 2025

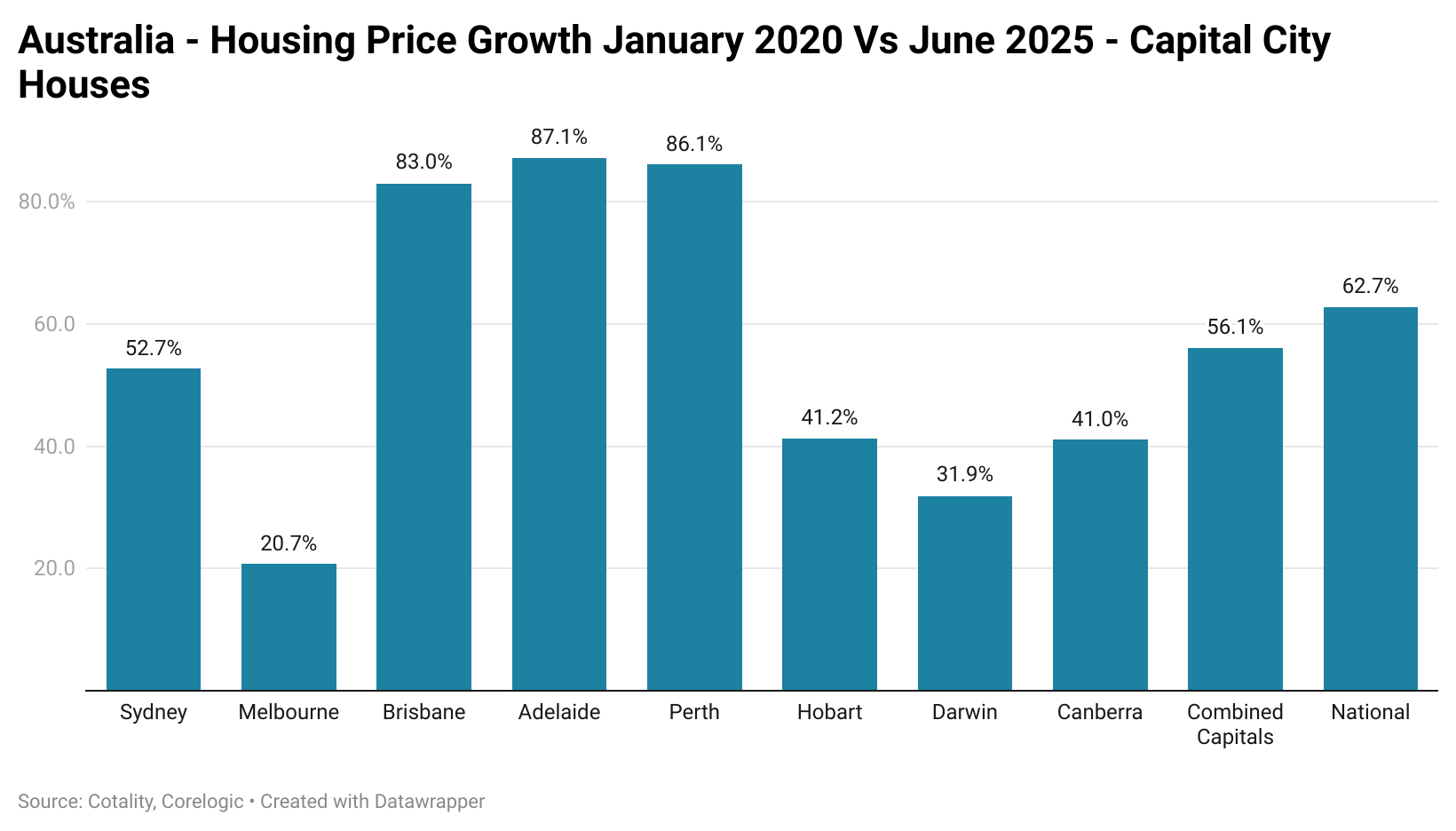

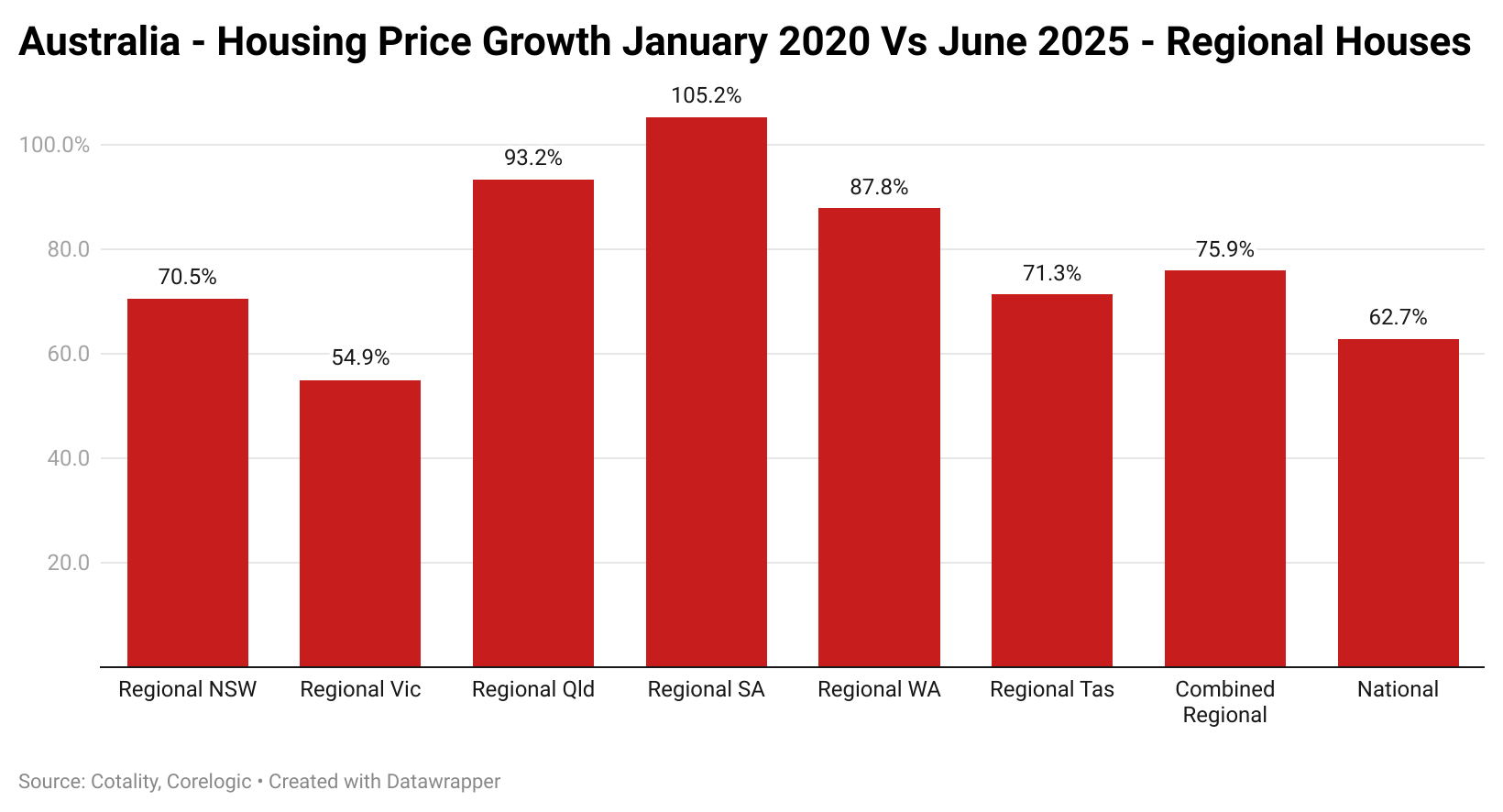

Looking at the numbers on the level of price growth seen across much of the nation since the onset of the pandemic, it’s clear why affordability has deteriorated so dramatically.

For better or worse, in the modern world, one’s level of freedom in how one lives can be heavily derived from housing costs. If housing costs are affordable or perhaps even cheap, then the freedom of choice to potentially have a parent spend more time at home with a young child in the formative years becomes more possible.

It can also grant the scope to dedicate one’s time to other pursuits, such as a small business, which can, in time, contribute to greater productivity at a national aggregate level.

Australia’s policymakers have been crimping this freedom for over two decades.