In the history of the U.S economy, every now and then there is a major shift in the balance of forces impacting the path of both growth and economic policy.

While the coverage of this most recent shift has so far flown under the radar, it represents a major demographic alteration to the U.S. labour market akin to the impact of Baby Boomers entering the workplace en masse in the late 1960s and 1970s.

It comes down to two major factors: the slowing in the growth of the domestically born U.S. labour force and the significant reduction in the rate of immigration into the U.S.

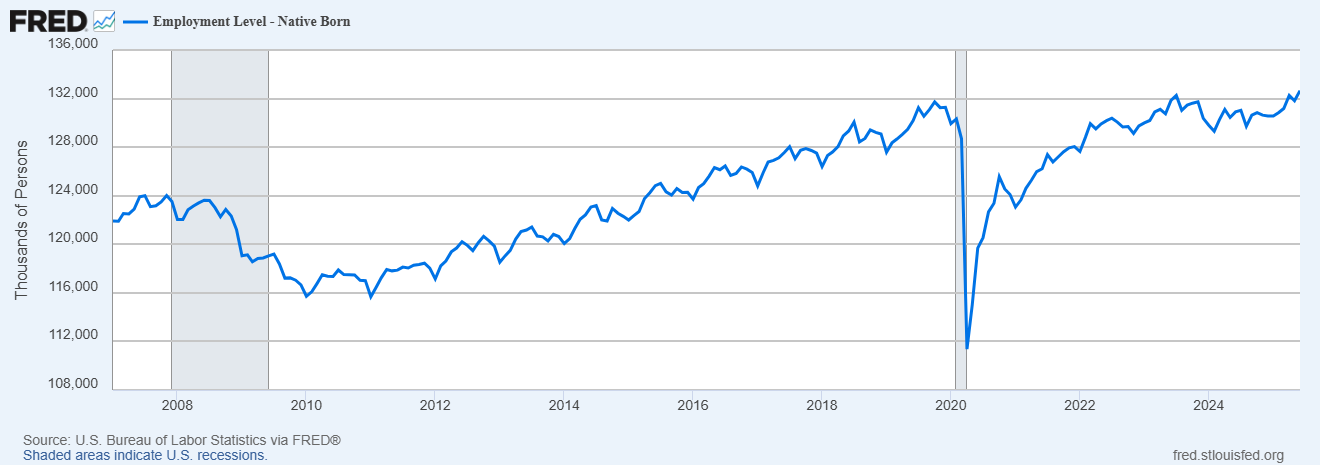

In the more than five years since the pre-pandemic high for native U.S. born employment levels in October 2019, cumulative growth on this metric has grown by a total of 931,000 or by 0.7%.

Meanwhile, U.S. migration rates were already low compared with most of Europe and a small fraction of Australia’s, yet the data suggests that they will be further curtailed in net terms.

According to the economists from the from the Brooking’s Institution, Wendy Edelberg, Tara Watson, and Stan Veuger:

“For the year as a whole, we think it’s likely (immigration) will be negative”

“It certainly would be the first time in more than 50 years.”

The impact of this shift on the U.S. labour market will be seismic.

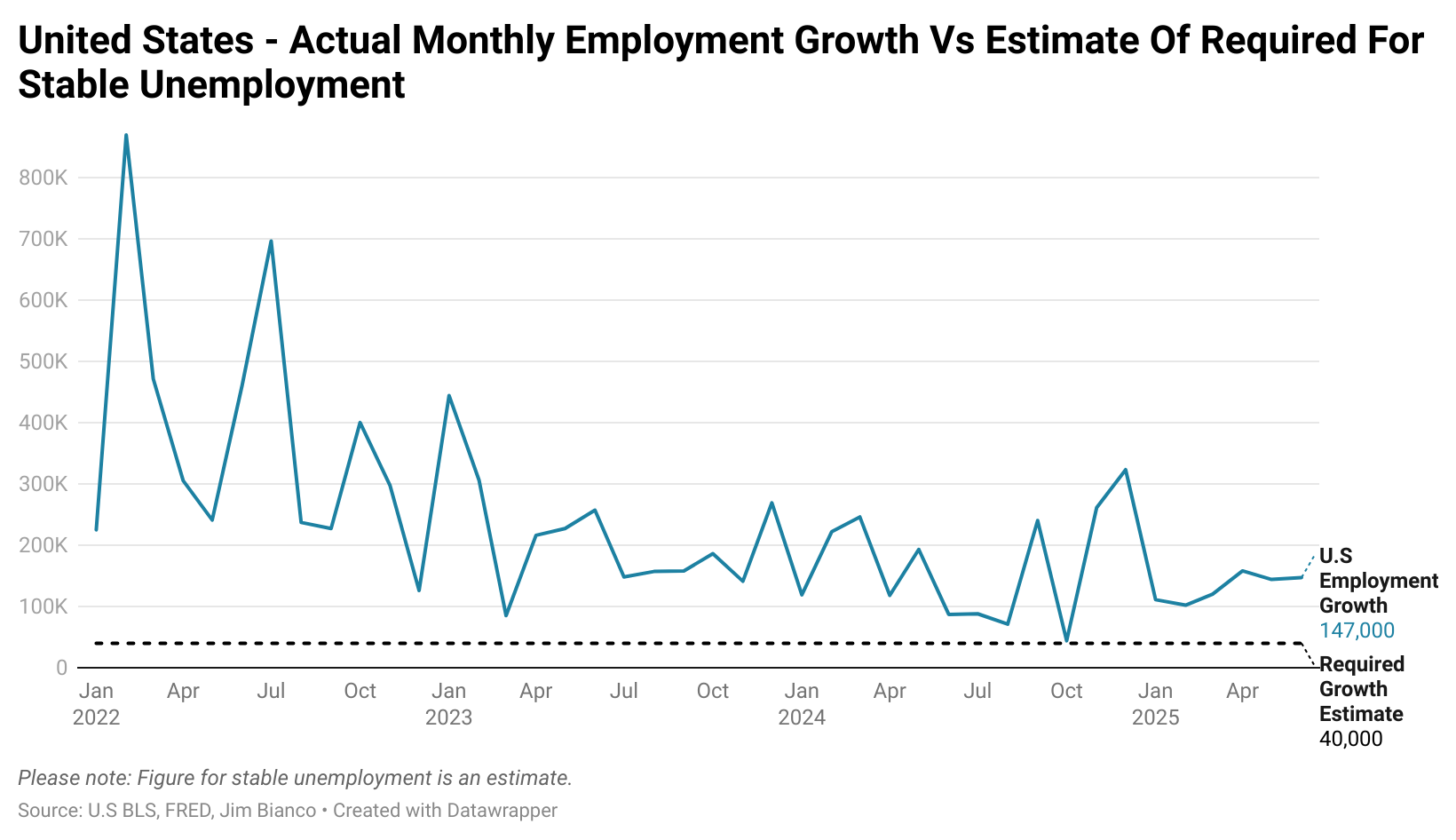

In the words of Macro Strategist Jim Bianco in a recent Twitter post:

“Slowing immigration, increased deportations, and the continuing low fertility rate (for decades), means population growth has really slowed.

This has lead some estimates that the economy now only needs to create 20k to 40k jobs a month to meet the now lower population growth.

So yes, 74k private sector jobs is slowing. But it’s more than enough to meet the economy’s needs. The bond market reacted appropriately given this reality.”

In short, if U.S. labour force growth is reduced to the degree that is anticipated, the U.S. economy would not see rising levels of unemployment even if month after month were a continuous repeat of the single worst post-pandemic monthly result.

This leaves American workers with a much greater economic buffer in aggregate, where far more can go wrong before there is a significant rise in unemployment.

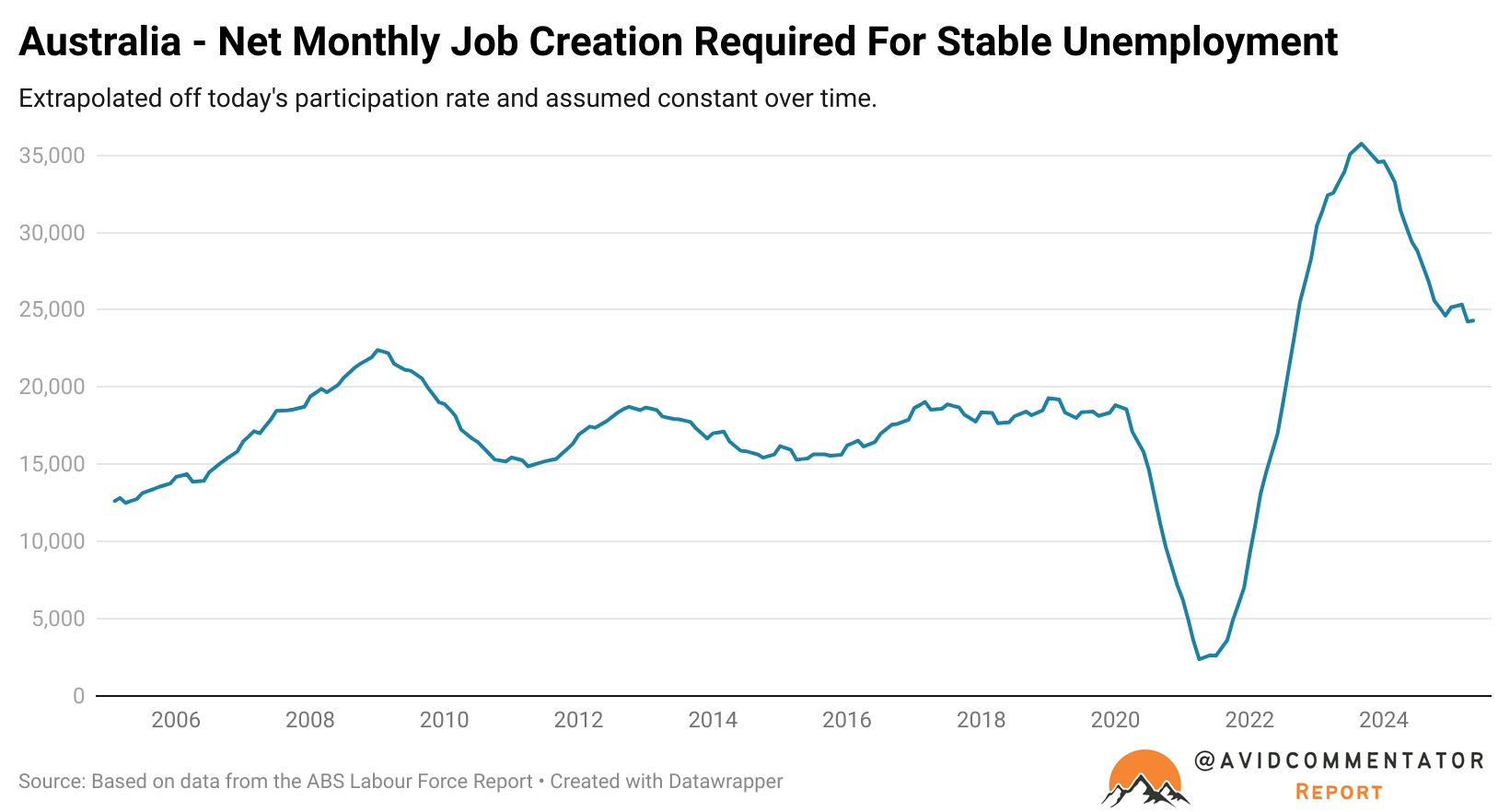

This is more or less the complete opposite of how settings in Australia currently stand.

If we take the upper end of the estimate put forward by Jim Bianco, the U.S. economy only needs to create jobs equivalent to 0.0235% of the total workforce each month to keep unemployment stable.

If we then apply the same metric to the Australian labour market based on a constant participation rate and the 12-month rolling rate of working age population growth, monthly employment growth of 0.159% of the labour force is required each month.

This leaves the Australian economy needing roughly 6.8 times the amount of jobs growth per capita as the U.S to keep the unemployment rate stable.

Given concerns about the impact of AI on the labour market and slowing levels of wage growth, there are questions about whether Australia is pursuing the right strategy given the circumstances.

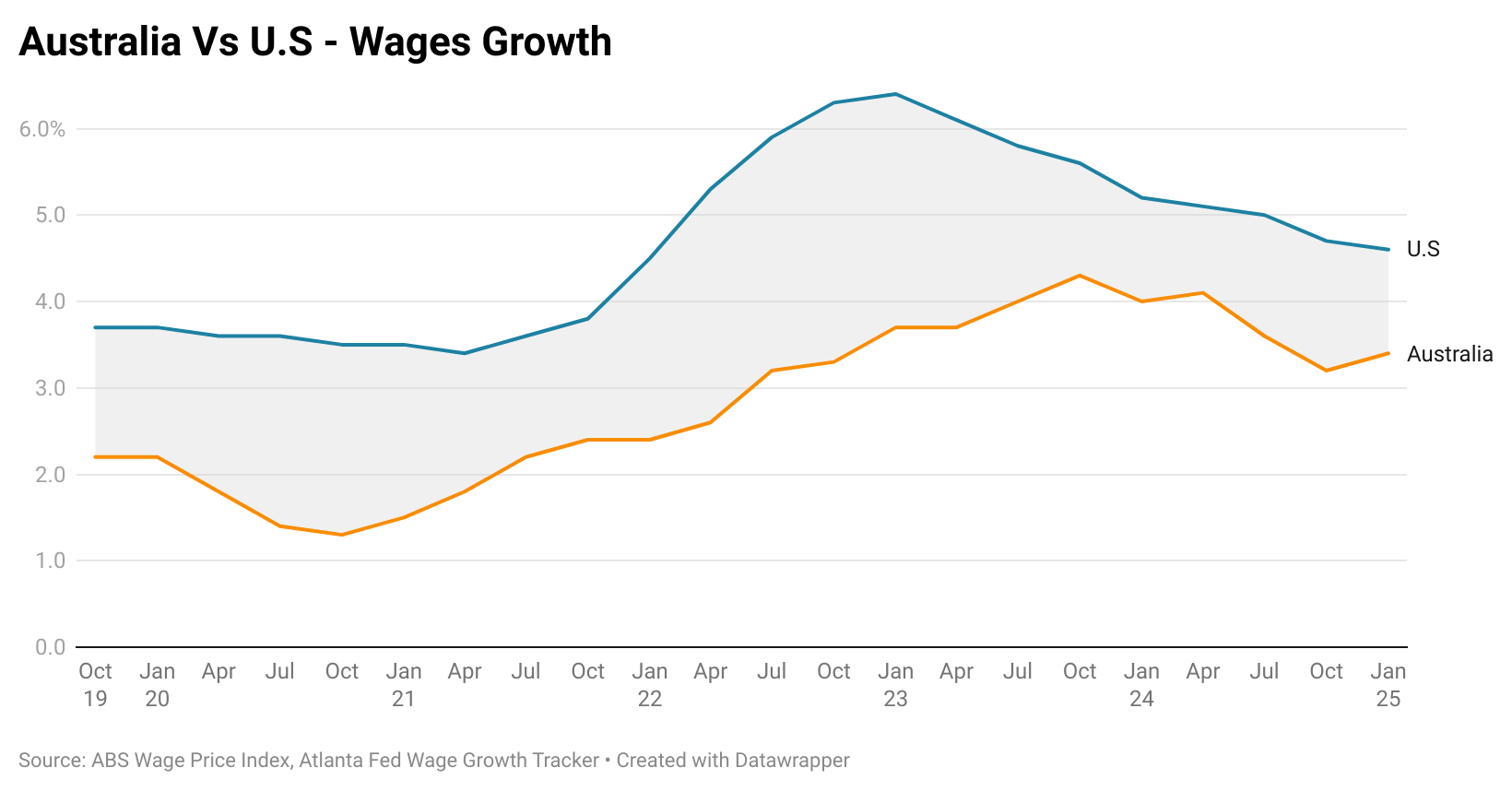

While less migration will mean less growth potential in terms of headline GDP for the U.S. economy, on the other hand, it will mean a comparatively tighter labour market and better wage growth prospects and higher productivity than would otherwise exist.

On the other side of the coin, the fact that U.S. jobs growth can slow to a relative crawl without a rise in unemployment means the U.S Federal Reserve with plenty of room to maneuver and can potentially continue to wait and see.

This is a much more youth-friendly macro mix, as housing values are stable while real wages climb.