If there is one country that has come to embody the absolute failure of developed world policymakers to address existential economic and social issues, it is South Korea.

Despite it’s status as one of the most technologically advanced economies in the world and one of only a relative handful to reach developed world status outside of the Western world and a select few oil rich nations, South Korea is effectively in the process of committing civilizational suicide.

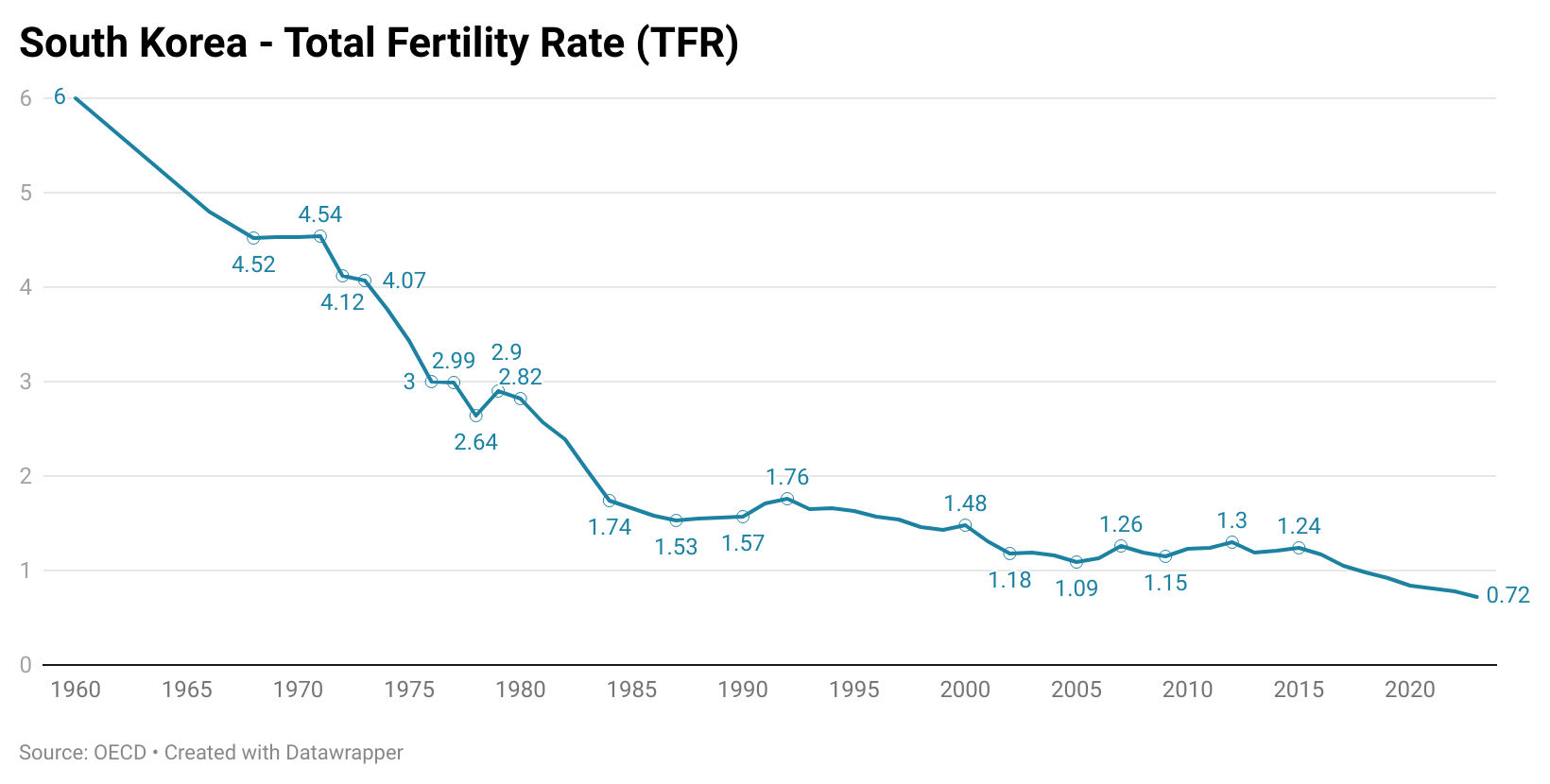

The total fertility rate or TFR for South Korea in 2024 was the lowest in the world. With an average of just 0.75 babies being born across a woman’s lifetime, roughly 1/3 of the required 2.1 for a population to sustain itself at the current level in the long term.

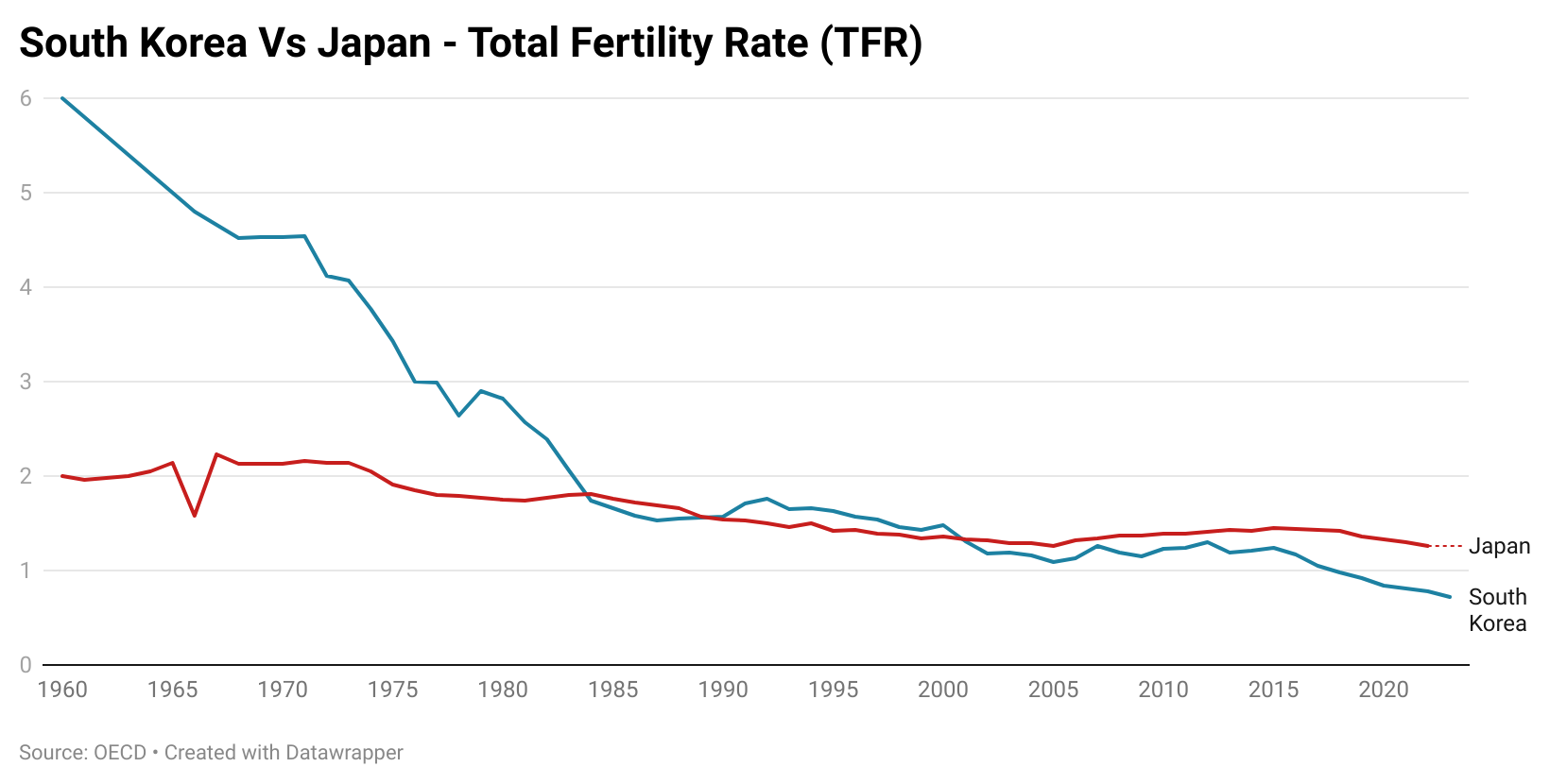

But let’s bring the demographic decline champion in the broader collective consciousness into the equation, Japan.

Despite Japan’s reputation for demographic decline, which began decades before South Korea’s, Japan’s TFR is 53.3% higher. Still an extremely concerning level, but a relative world away from the world beating collapse occurring just across the Sea of Japan.

The factors influencing this dramatic deterioration are legion. Issues with work/life balance are extremely common, as are patriarchal perspectives on the role and treatment of women in society.

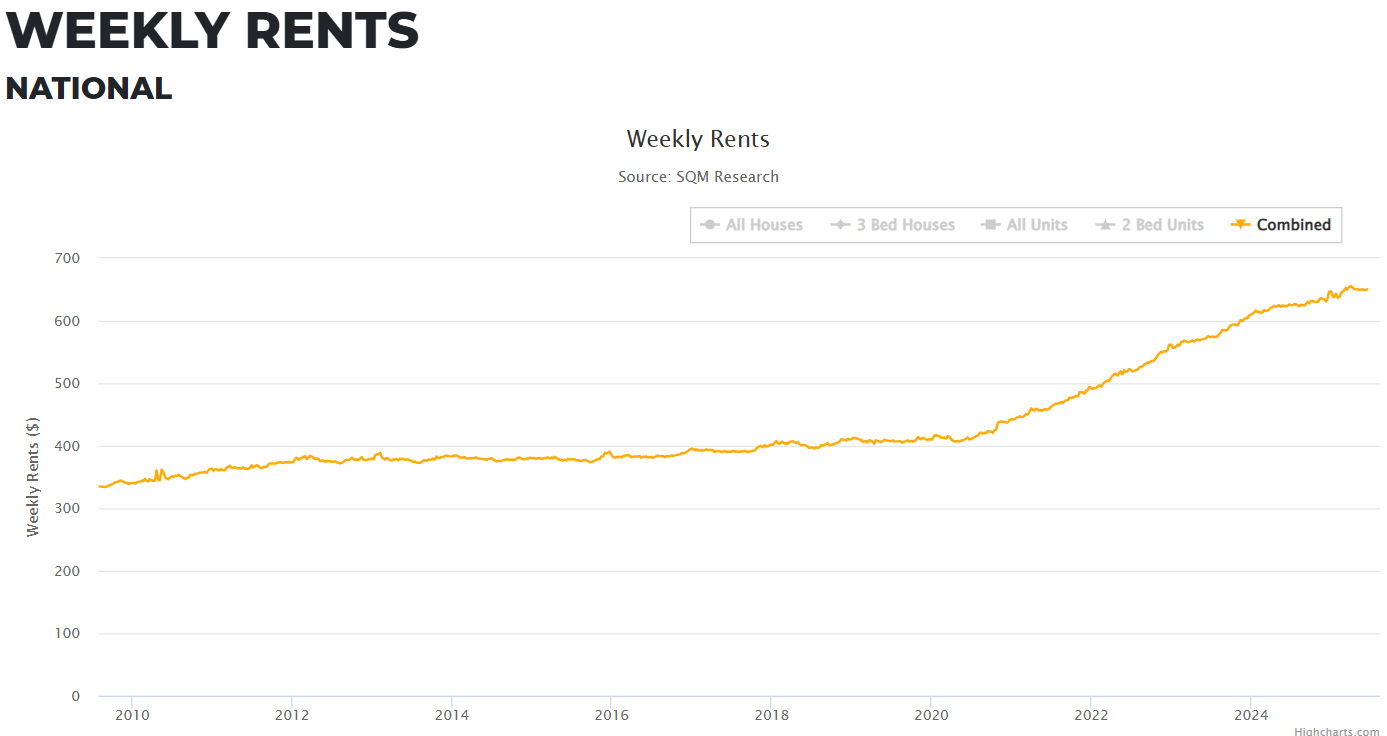

On the economics side of things, South Korean academia has concluded in multiple studies that one of the major drivers of the fall in fertility rates is the cost of housing.

According to a study from the Korea Research Institute for Human Settlements, for each 10% rise in annual housing prices the total fertility rate would decline by 0.02. Meanwhile a 10% annual rise in rents would drive a decline of 0.0247.

Considering that the effect is compounded over time, the impact over a long term time horizon is highly significant.

This echoes the findings of several reports by HSBC, which Leith covered a few weeks ago.

To very briefly recap:

Research from HSBC shows that “a 10% increase in house prices leads to a 1.3% drop in birth rates, and an even sharper fall among renters”.

The issues that the people of South Korea have with the drive to further propagate their society are abundantly clear, but the efforts of policymakers to counter these various issues has been far too limited. And in a trend that will shock pretty much none of you, the government continues to pander the interests of existing stakeholders, despite the severe demographic and eventual economic damage it will inflict on South Korea as a nation.

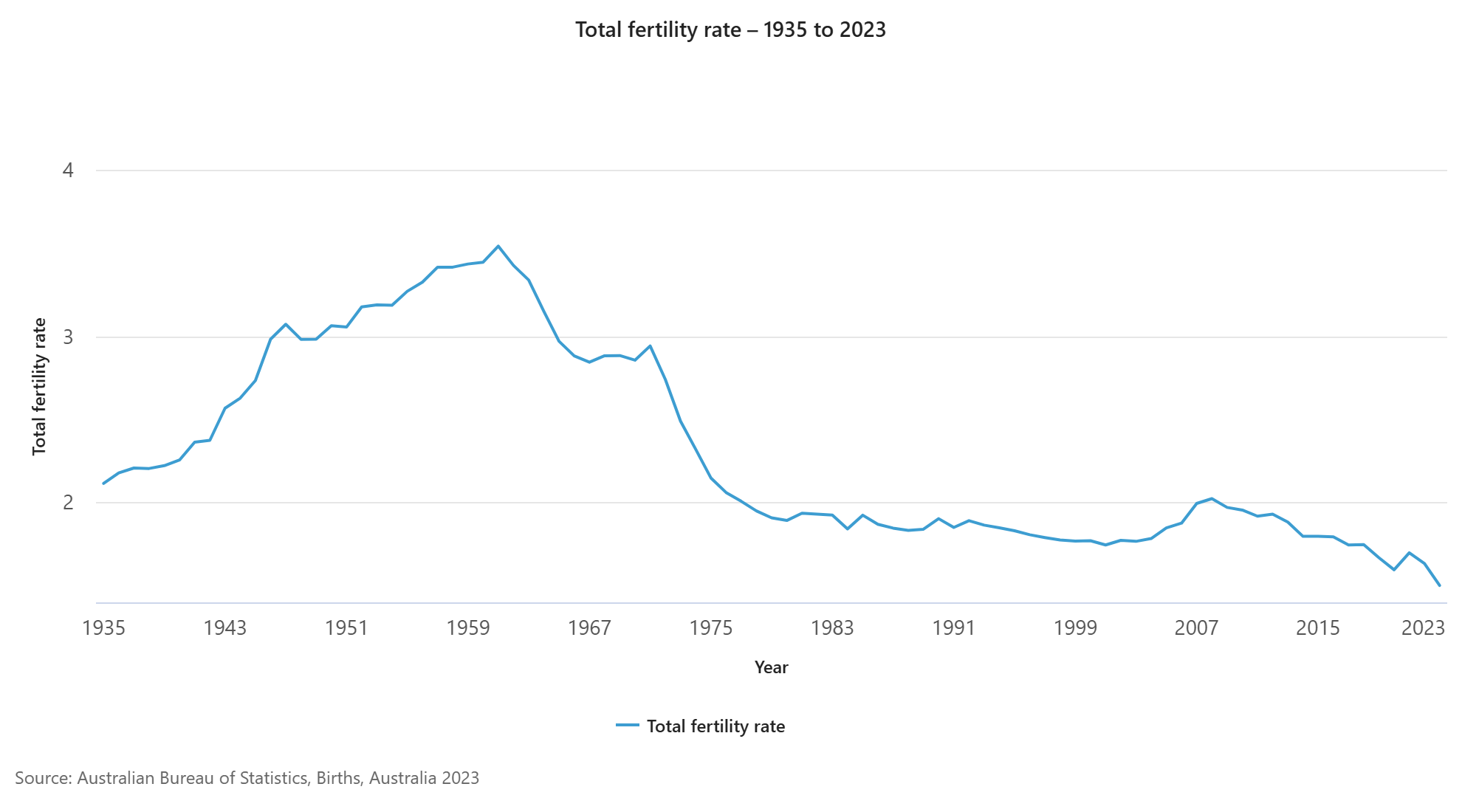

Meanwhile, Australia’s fertility rate in 2023 was 1.5, roughly double that of South Korea, but the downward trend is clear.

While the barriers to entry into the housing market have got higher and higher over time, the fall in Australia’s fertility rate was arguably partially mitigated by relatively low levels of rental price growth between 2012 and 2020.

But with the surge in rents from late 2020 onwards, compounded by the rental availability crisis, that particular pillar of support has seemingly been removed.

With both sides of the major party political divide committed to a strategy that will at best deliver affordable housing at a national level some time in the 2040s even if housing prices were to flatline, Australia’s fertility rate appears set to continue to trend down for the foreseeable future.

It was once said that turning Japanese (referencing that nation’s lost decade) was the threat, but the data reveals the risk of an arguably much worse fate, our nation’s demographics turning Korean.