In recent weeks the issue of AI has been on the Albanese government’s agenda, as the run-up to the government’s “roundtable” on productivity continues.

Treasurer Jim Chalmers has thrown his weight behind soft-touch regulation of AI, emphasising that the government’s priority is how it can be used to boost productivity rather than establishing guardrails for its usage.

For better or worse, AI is going to impact Australia’s labour market in the coming years, particularly once it reaches its implementation tipping point amongst business owners.

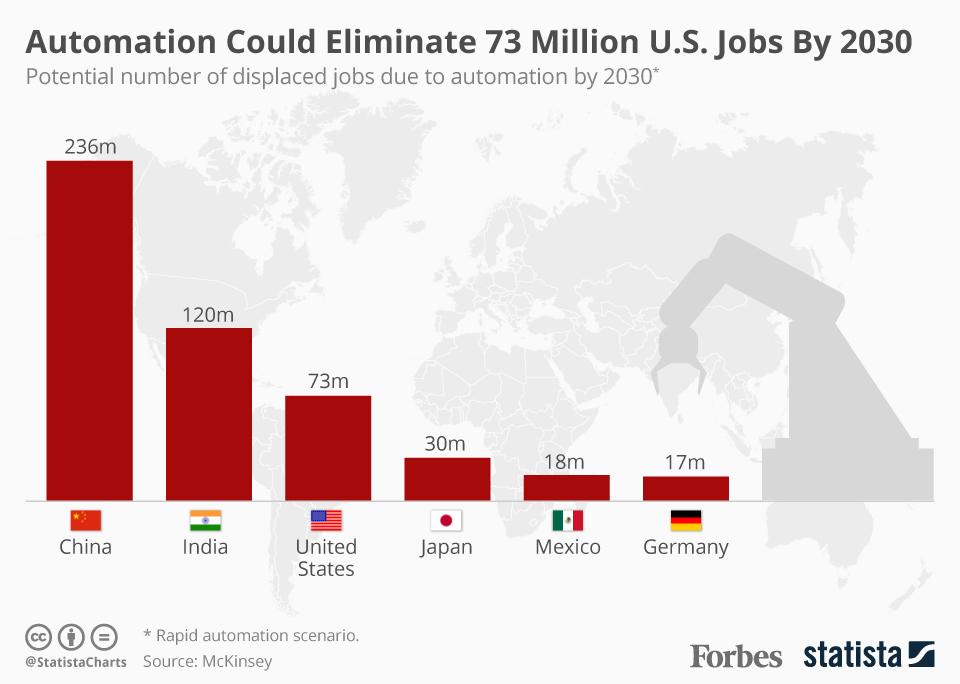

According to a report from consulting firm McKinsey, it is projected that by 2030, up to 30% of current U.S. jobs could be automated using AI, with up to 60% significantly altered by AI tools.

While there is skepticism that the implementation of AI will be so impactful so swiftly (which I share), the reality is that if AI is able to have even half that impact by 2030, the impact on the labour market would be sizable.

Industrial Revolution Employment Shifts

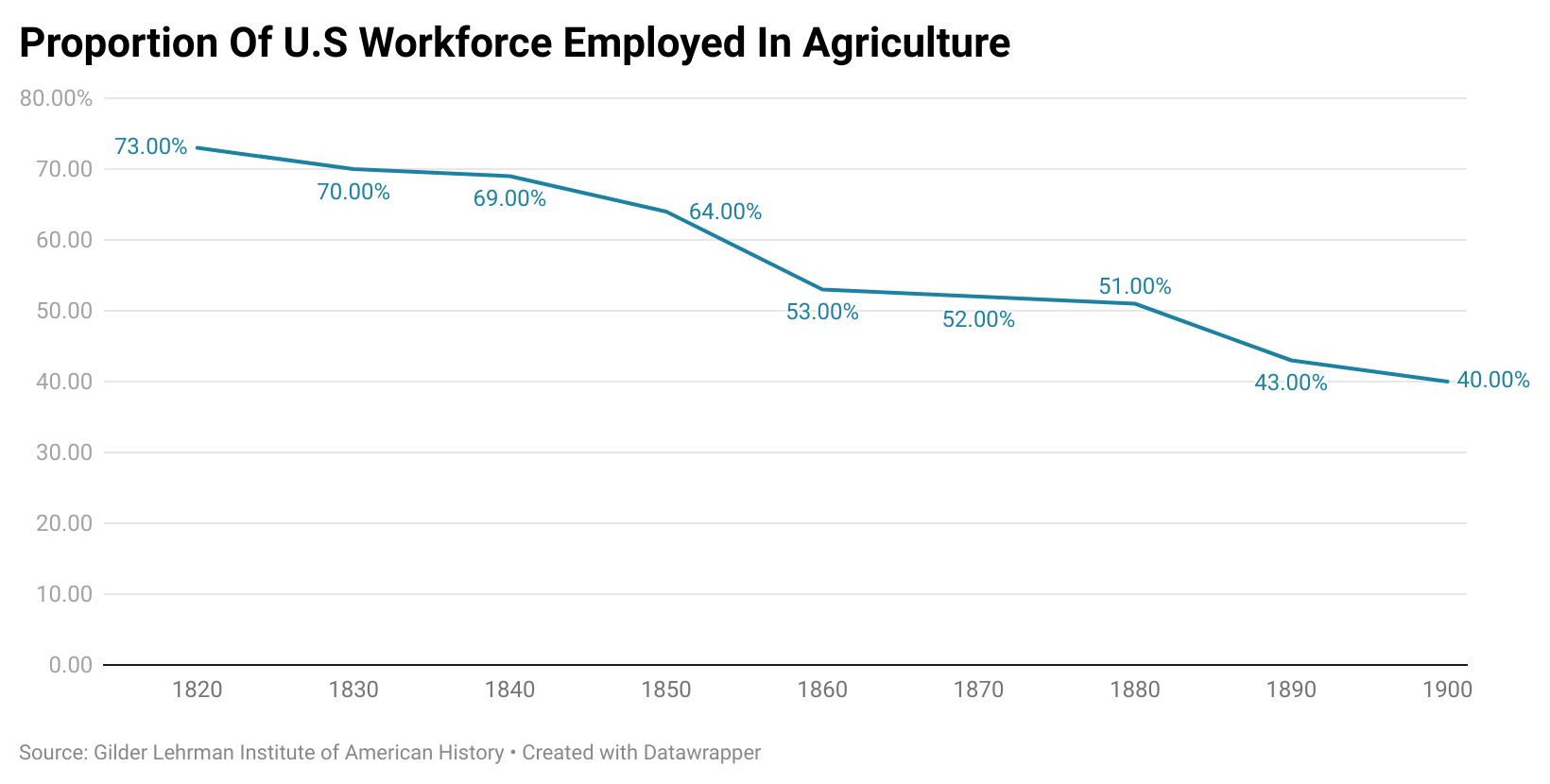

Some have put forward the Industrial Revolution in the 19th and early 20th century as an example of how dramatic technological progress need not be a negative for workers as a whole.

But there are several major divergences between the claimed potential of an AI rollout and the Industrial Revolution.

The Industrial Revolution took place over more than a century, with the impact on the labour market occurring gradually at an aggregate level.

For example, in the United States between 1860 and 1900, the proportion of the labour force employed in agriculture declined from 53% to 40%.

While this represents a seismic shift in the source of employment, it occurred relatively gradually and the still labour intensive new industries provided plenty of new job opportunities in time.

Technological Propagation

Another important difference between AI and the Industrial Revolution is that one is largely software for the overwhelming majority of businesses, costing less than the office’s monthly budgets for coffee.

At the other end of the spectrum, the Industrial Revolution was entirely based on hardware, which had high costs and required a significant ongoing financial commitment to keep the new machinery maintained.

For example, in Britain in 1830, a threshing machine (which separates grain seeds from stalks and husks) cost roughly 5 times the annual full-time wage of a farmer or more. The propagation of threshing machines in the 1820’s in Britain would eventually culminate in the ‘Swing Riots’ in 1830, which would prompt concerns in the British government of a full-blown uprising.

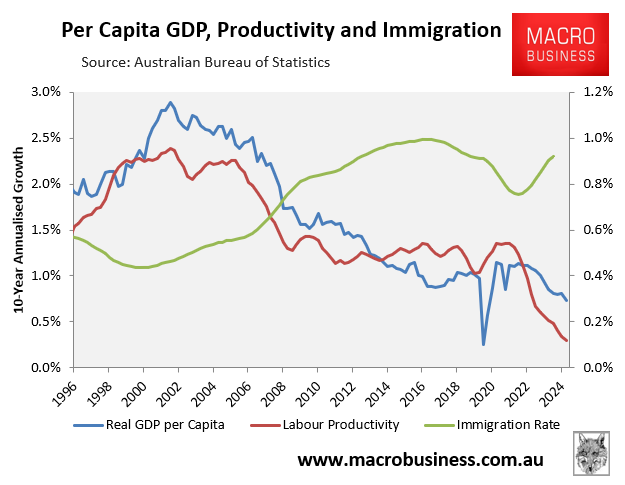

Australian economy more vulnerable than most

As we know, Australia runs an immigration-led, labour market expansion economic model. The most obvious feature of this model is that it is disproductive via capital shallowing. That is, the Aussie economy tends to displace technology with poor, imported people.

Needless to say, if AI proves to be disruptive for entry-level employment, this model will be more severely impaired than more traditional business investment-led growth.

Indeed, given Canberra’s only policy response to any economic shock appears to be to increase immigration, in part to support overblown house prices, successful AI will put Treasury in quite a pickle.

The Takeaway

While there is scepticism that AI will create the level of labour market disruption on the timeline that the likes of McKinsey project, it doesn’t need to have anything like that impact to have a profound impact on the labour market in Australia and around the world.

If it renders even 5% of the workforce more or less unemployable due to a lack of the required innate talents and skills to adapt to this new employment landscape, the impact on everything from government budgets to politics would in time be highly significant.

That seems to be one of the vital takeaways of the entire AI debate. It doesn’t need to fully realize its projected potential impact on the labour market; even a fraction of that could still be enough to quite literally decimate the ranks of Australia’s workforce and threaten its economic model (which would be no bad thing).