I’ve just returned from a week at the beach with my family (it was lovely, thanks for asking). One thing that stands out as a key function of parenting in the Summer beach environment is making sure your child avoids sunburn.

This got me thinking about a world without sunscreen. This cheap little cream enables us to withstand sun exposure like super-humans, avoid painful sunburn, and partake in activities that would be out of the question in a ‘no sunscreen’ world.

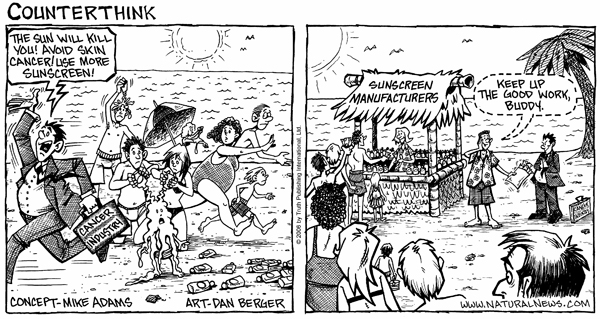

Since sunscreen allows us to tolerate so much more exposure to the sun, is it actually contributing in some way to increased incidence of skin cancer? Are the net health benefits of sunscreen actually much lower, or even negative, because of our change in behaviour? How big is the sunscreen rebound effect?

There seems to be some acceptance of the sunscreen rebound effect. This article, for example, states that sunburn may even protect against melanoma – by keeping people out of the sun.

Again here:

The Australian experience provides the first clue. The rise in melanoma has been exceptionally high in Queensland where the medical establishment has long and vigorously promoted the use of sunscreens. Queensland now has more incidences of melanoma per capita than any other place. Worldwide, the greatest rise in melanoma has been experienced in countries where chemical sunscreens have been heavily promoted.

And here:

sunscreen use tends to prolong the amount of time people spend in the sun while they are on vacation—and that only sunburn modifies the behavior of sun-seekers

And here:

Sunscreens suppress natural warnings of overexposure to the sun and allow excessive exposure to wavelengths ofsunlight which they do not block. Because sunscreens create a false sense of security, more effective measures to reduce sunlight exposure, such as limiting time spent in the sun or use of hats and clothing, may be ignored.

My experience suggests that all of these statements are true to some degree.

If everything was held constant – time in the sun, covered clothing, etc (notice the decline in hat wearing in the past few decades?) – then sunscreen may be quite effective at preventing skin cancer. But humans have a tendency to adjust their behaviour to take maximum advantage of such innovations. In some circles it is known as the Peltzman effect, in others, this behaviour is known as risk compensation. Certainly the effect is real, we just don’t have the evidence to know how large the net health benefit from sunscreen really is.

Due to the plethora of uncontrollable variable in any longitudinal study, I’m not sure that we will ever have definitive statistical evidence for this.

Surprisingly, high rates of skin cancer is a very uniquely Australian problem. The map below shows that Australia stands in a category of its own in terms of melanoma rates. One reason could be that we are one of the few tropical countries full of fair skinned Europeans, living an outdoors life style. I also have suspicions that tanning salons are the cause of high melanoma rates for Icelandic women.

Given the importance of skin cancer to the health of Australians, the net health benefits of the current strategy of sunscreen promotion should be assessed in light of the predictable behavioural adjustments we are likely to make.

Tips, suggestions, comments and requests to rumplestatskin@gmail.com + follow me on Twitter@rumplestatskin