The Australian’s Robert Gottliebsen has outlined a bunch of supply-side impediments that are driving the nation’s housing crisis.

Gotti cited Brickworks CEO, Lindsay Partridge, who contends that the nation’s immigration policy should focus more on attracting tradespeople, because there is a shortage of workers who can build houses.

Gotti also argued that action is needed to speed up the process of approving housing developments, given that it can take 6-9 months to have a development application approved.

Likewise, state government infrastructure projects are absorbing tradespeople and skilled professionals such as architects who could have been contributing to the nation’s housing supply.

“We need local media to highlight the real culprits [of the housing crisis]”, Gotti claims. “Currently, that simply does not happen”.

In a similar vein, Robert Harley celebrated this week’s AFR Housing Summit claiming that a consensus has been achieved that the key to affordability is delivering more supply:

“The Albanese team is the first federal government in decades to focus on housing supply… the broader issues of planning, infrastructure delivery, construction bottlenecks, and the less understood constraints of finance”.

“The key issues, stressed by speaker after speaker at the Financial Review Property Summit, are the challenges of planning, construction and finance”.

“Planning is not just about zoning, but about all the costs and delays”.

“Construction is not just about prices but also capacity constraints. Master Builders Australia chief executive Denita Wawn points out that her industry would need 500,000 new entrants to meet the Albanese government’s targets”.

Robert Harley conveniently failed to mention Shane Oliver’s seminal statement at the AFR Housing Summit explaining that Australia’s chronic housing shortage has been caused by the large increase in immigration levels from 2005.

Therefore, the solution to the housing crisis, according to Oliver, is to lower immigration to a level where supply can realistically catch up:

“If you go back to the early post-1990s recession, immigration levels were about 120,000 per annum. Then they jumped up to 250,000 to 260,000 per annum”.

“So you really got 150,000 extra population through that period”.

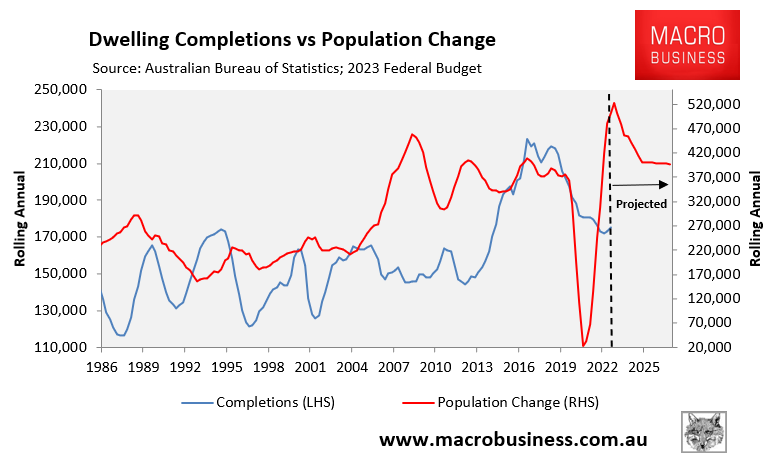

“But if you look at the completions of dwellings, it didn’t really jump up until we had the apartment building boom briefly from 2015 to 2018”.

“And that’s the real issue here. We pump people into the economy and then we all go ‘surprise, surprise’, house prices are expensive. We’ve got a housing affordability problem”.

“Of course we’re going to have that problem. I think we do need to calibrate those immigration levels to the ability of the property market to supply new property and to allow each year for that cumulative undersupply to be whittled away”.

The next chart illustrates Shane Oliver’s claims:

Clearly, the projected 1.5 million net overseas migration over five years projected in the May federal budget will make Australia’s housing crisis worse. There is simply no way that Australia can ever build enough homes to keep pace with such strong demand.

When it comes to Australia’s housing crisis, the federal government’s extreme immigration policy clearly takes the lion’s share of the blame.

It is time for media commentators to accept this reality and to demand lower, sustainable levels of immigration.