The Albanese government is reportedly avoiding a hard cap on foreign student numbers to avoid long-term damage to education exports.

International students are the largest contributor to the politically sensitive net overseas migration number and are contributing to the rental crisis.

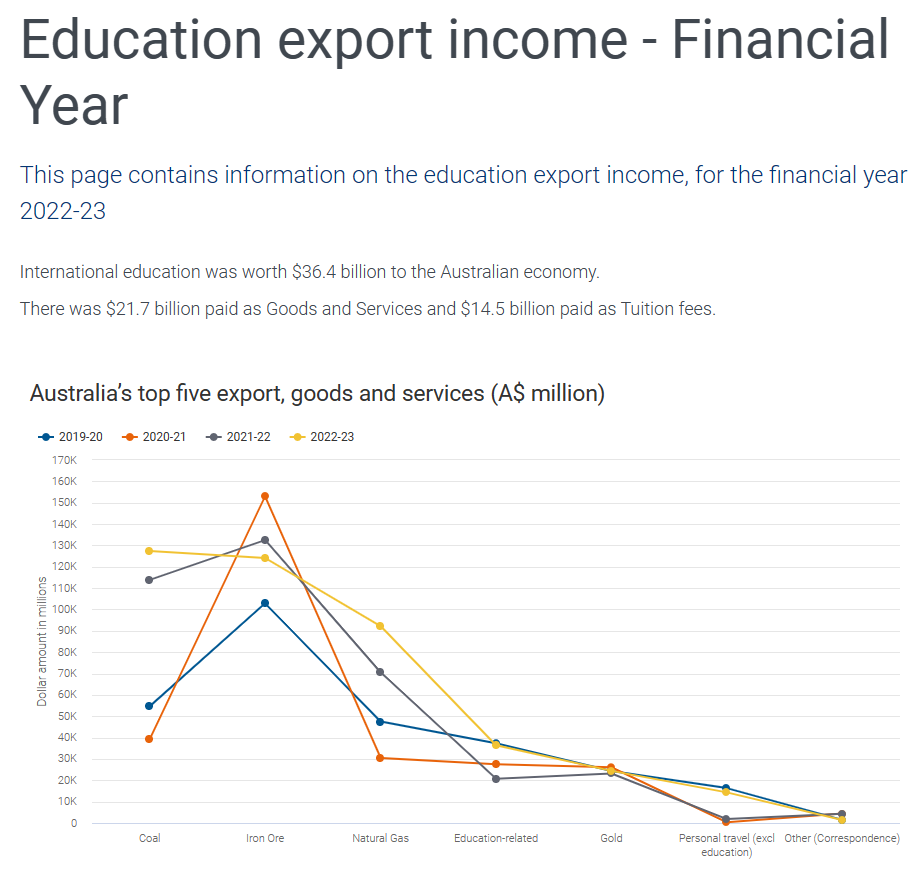

However, the government is also concerned about harming what it claims is the country’s second-largest export market after commodities.

“It would be cutting off our nose to spite our face”, one source said.

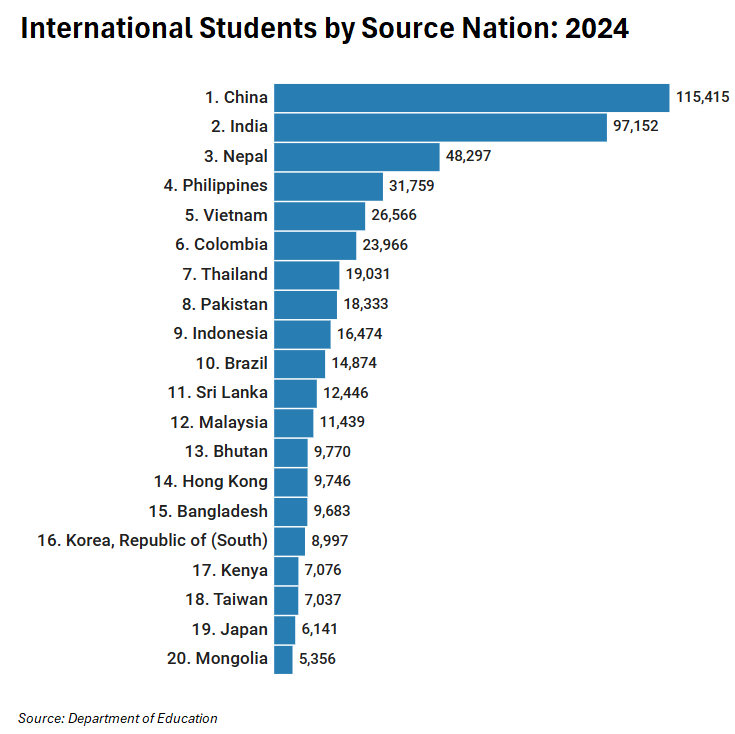

The government is also sensitive to the politics of alienating voters in the large Chinese and Indian communities, whose countries of origin have been the most lucrative source of foreign students.

Sources close to the government suggest that “the concept of sustainable management or measured growth is a style of cap, just more generous”.

The $710 visa application fee for foreign students is expected to be dramatically increased in the upcoming budget, with speculation that it could be as high as $2100.

Other options include requiring universities to build more student accommodation in return for “measured growth” in overseas students.

Treasurer Jim Chalmers and Education Minister Jason Clare have reportedly argued internally in favour of “sustainably” managing student numbers rather than through a hard cap.

The notion that the federal government should tread lightly because international education is a major export industry is demonstrably false.

International education is a people-importing industry, not a genuine export industry.

The ABS export figures are fake because they count all expenditures by foreign students in Australia as exports, even if the money used to pay for those expenditures is earned working in Australia.

Most student visa holders are from low-income countries and begin working in Australia immediately to cover their living and tuition costs.

As explained by Associate Professor Salvatore Babones in his recent book, “Australia’s universities, can they reform”:

“In reality, everyone (except perhaps the government and the universities) knew that many international students pay for their courses out of the proceeds of their work in-country, often working excessive hours under exploitative conditions, in violation of their visa terms”.

“This situation is especially common among South Asian students, and is reflected in the steep fall-off in South Asian student numbers when teaching moved online”.

“With prospective students unable to rely on employment income in Australia to support their studies, new commencements of Indian students at Australian higher education providers fell 65% between 2019 and 2021; for Nepali students, the decline was 37%; for Pakistanis, 45%; for Sri Lankans, 54%”.

“These countries are simply too poor to send large cohorts of international students to Australian universities based on family resources alone”.

“For many South Asian students, a student visa is a very expensive but thinly disguised work visa”.

This is why we have read so many stories about international students struggling to make ends meet and relying on charities and food banks, as well as pleas for more public assistance for overseas students.

Many ‘students’ have also registered at low-cost private colleges with the intention of permanently living and working in Australia.

The inaccurate measurement of education exports gives the impression that the industry is a large earner for Australia.

The reality is that the vast bulk of this “export” money is generated within Australia in low-skilled and low-paying vocations such as driving Uber.

Moreover, the falsity of the education export number has increased as Australia’s international student numbers have shifted away from Chinese students, who are wealthier and less likely to work, to poorer students from South Asia.

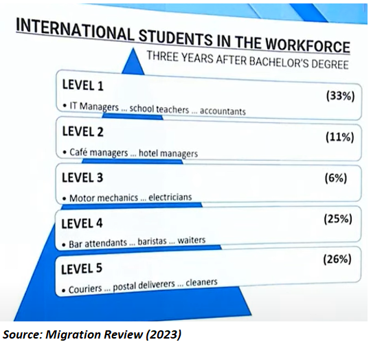

Labor’s Migration Review revealed that more than half (51%) of international student graduates with bachelor’s degrees were working in low-skilled jobs three years after graduation:

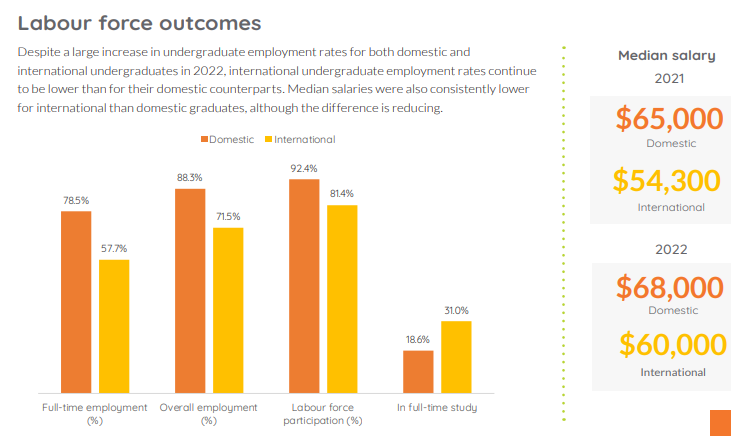

These findings are supported by the latest Graduate Outcomes Survey (GOS), which shows that international employment rates, participation rates and median salaries are well below those of domestic graduates:

Source: Graduate Outcomes Survey (2022)

It is a sad indictment on Australia’s universities that they are producing so many international graduates that work in low-skilled and low-paid jobs. It is also one of the drivers of Australia’s low productivity.

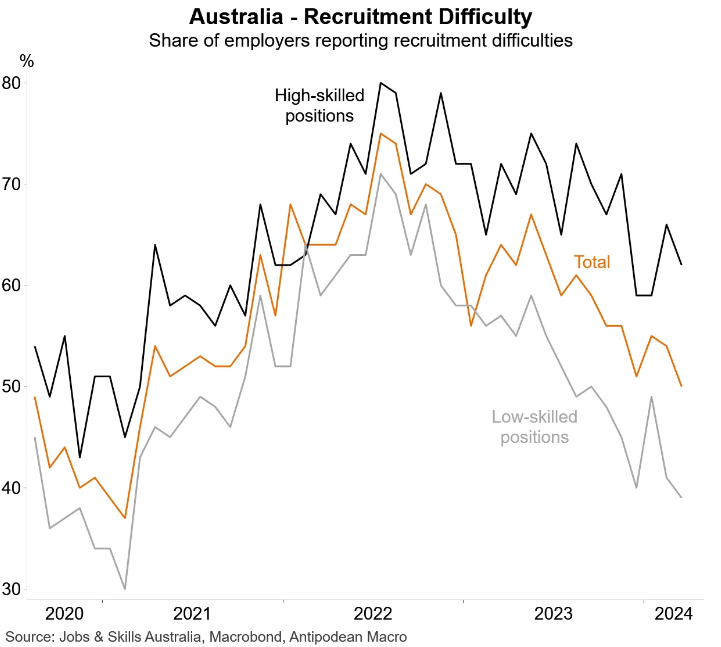

Indeed, the tsunami of international students has helped to oversupply the economy with low-skilled workers, driving up youth unemployment:

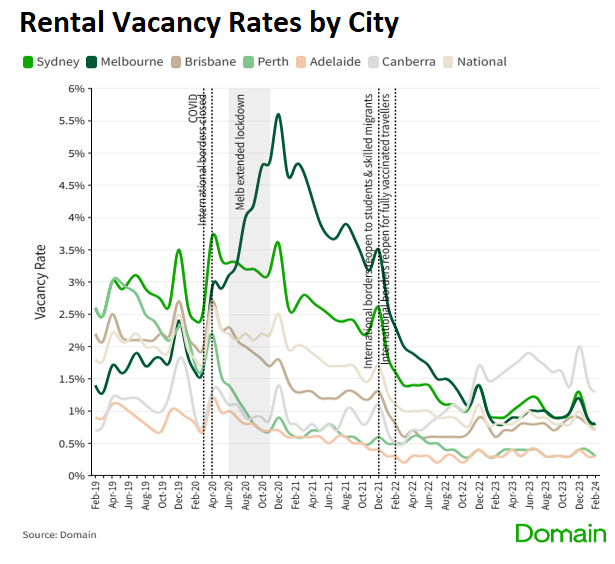

The tidal wave of students has also helped drive rental vacancy rates to record lows, which is significantly harming younger and poorer Australians:

International education was never a true “export”. It is the primary channel for Australia’s immigration Ponzi scheme, which raises housing costs, overburdens infrastructure, and reduces wages, lowering overall living standards.

If Labor was serious about cracking down on the international education sector, it would:

- Raise financial barriers to entry (i.e., how much funds a student must have available before arriving in Australia).

- Significantly increase entrance requirements (e.g. English language proficiency and academic testing).

- Raise pedagogical standards.

- Abolish group assignments.

- Cut the clear link between studying, working, and permanent residency.

- Require universities to provide on-campus accommodation to international students in proportion to their enrolments.

Instead, the Albanese government went the other way last year, signing two migration agreements with India that, among other things, promise:

- Five-year student visas for Indians, with no caps on the numbers that can study in Australia.

- Indian graduates of Australian tertiary institutions on a student visa can apply to work without visa sponsorship for up to eight years.

- Australia will recognise Indian vocational and university graduates to be “holding the comparable AQF qualification” for the purposes of admission to higher education and general employment.

These migration pacts will make Australia an even more attractive destination and will likely increase the flow of lower-skilled Indians seeking work and residency in Australia.

Would you like fries with that?