A year of record population growth and falling rates of construction have delivered one of the worst housing crises on record.

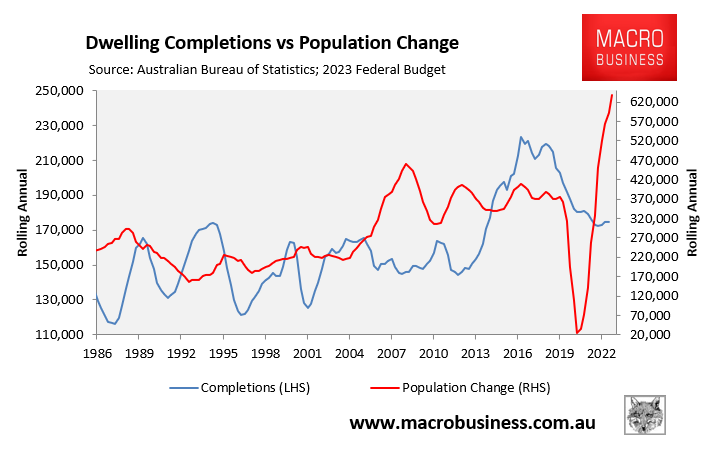

In the 2022-23 financial year, Australia’s population grew by a record 624,000 against only 174,000 dwelling completions.

While population growth is expected to moderate to around 500,000 in 2024 (i.e. the second highest level in history), the forward-looking indicators also point to a further slowing in dwelling construction, which will mean the shortfall in housing will continue to worsen.

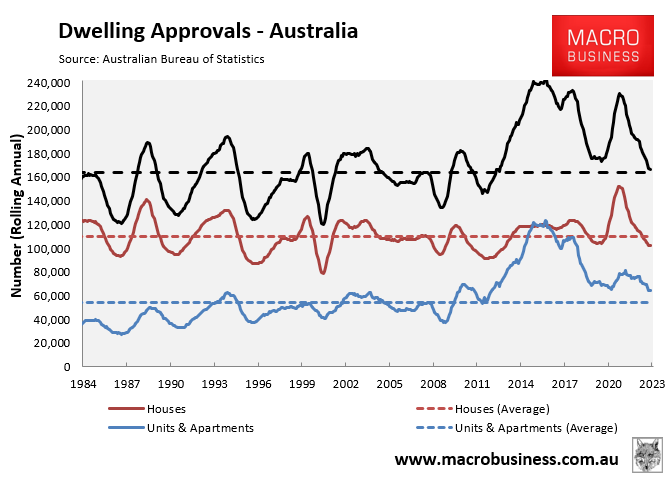

Annual dwelling approvals fell to a decade low in October to only 164,000:

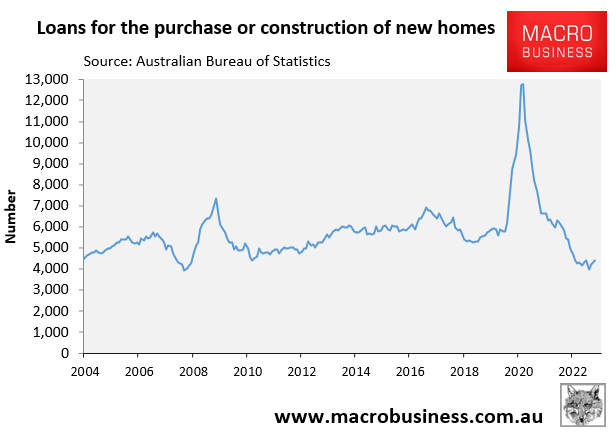

New home sales and the number of loans for the purchase or construction of a new home have also fallen to around decade lows:

Therefore, the housing shortfall is destined to worsen in 2024, completely obliterating the Albanese government’s delusional target of building 240,000 homes a year for five consecutive years (a level that has never been achieved before).

Benni Aroni, the developer of Melbourne’s Eureka Tower, told The AFR that while the need for housing remains strong, “the problem is that we just can’t make a feasibility work. And we can’t make a feasibility work because we haven’t [got] stability of cost and the cost of finance. And neither of those is going anywhere south in the next 12 to 24 months”.

The cost of building a new home continues to rise, albeit at a slower pace, and this has both tempered buyer demand made construction unviable.

Prices for key materials used in new home construction have soared since before the pandemic. For example, terracotta tiles have risen 62% since December 2019, timber windows have lifted 61%, and reinforcing steel has climbed 59%, reports The AFR.

Add a shortages of builders, insolvencies, and higher financing costs (interest rates) into the mix and there is simply no way that enough homes can be built to meet historically high immigration-driven demand.

This is why analysts like Jarden economist Carlos Cacho believe the Albanese government’s 1.2 million homes target over five years is delusional, citing barriers such as the 30% rise in construction costs and the 30% reduction in borrowing capacity.

“Despite housing prices picking up again, despite the chronic undersupply of housing, you haven’t seen a pick-up of sales,” he said. “On our numbers, we expect housing starts in calendar year 2024 to slow to about 155,000, which would be the lowest since 2012”, Cacho said.

“Something doesn’t seem to stack up. While new supply is badly needed, higher interest rates and construction cost means many potential buyers cannot afford new housing. Including land, we estimate new house costs are up 26 per cent since December 2019”.

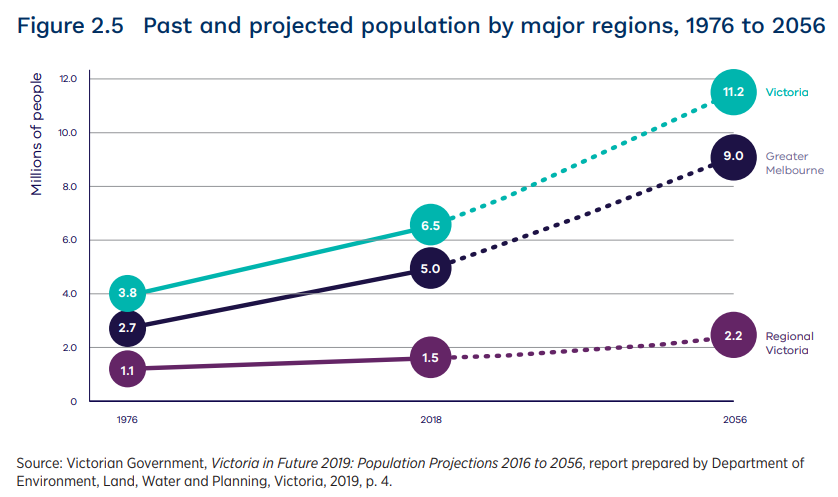

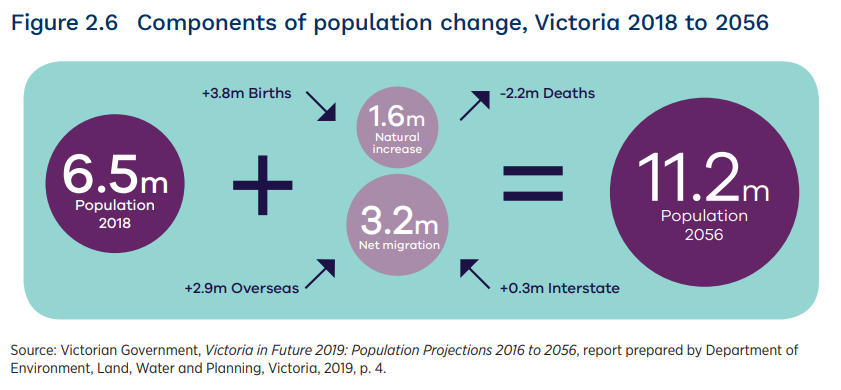

Meanwhile, the Victorian Government – which has trumped Albo with an even more delusional target of building 80,000 homes a year for 10 straight years – continues to gaslight that it is a supply problem rather than an excessive immigration problem:

“The Victorian government, which has its own goal of building 80,000 new homes annually for the next 10 years, said “bold” targets were necessary to meet population growth projections. Melbourne is expected to grow to 9 million people – the size of London – by 2050, up from 4.8 million today”.

“The status quo is not an option, and admiring the problem will only make it worse,” a Victorian government spokesman said. “Unless we take bold and decisive action now, Victorians will be paying the price for generations to come”.

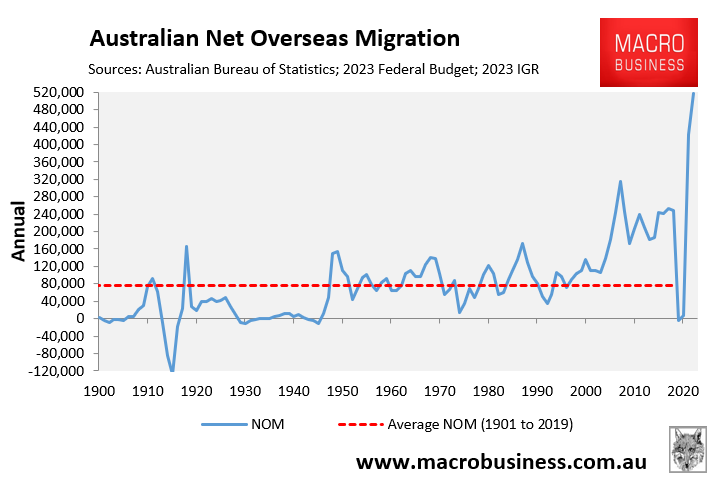

Melbourne would only grow to the “size of London by 2050” because of the federal government’s extreme immigration policy:

If the federal government simply reduced net overseas migration to the historical average of around 100,000 people a year:

Then our cities wouldn’t grow like cancer cells and we wouldn’t experience chronic housing shortages.

It’s the extreme immigration, stupid!