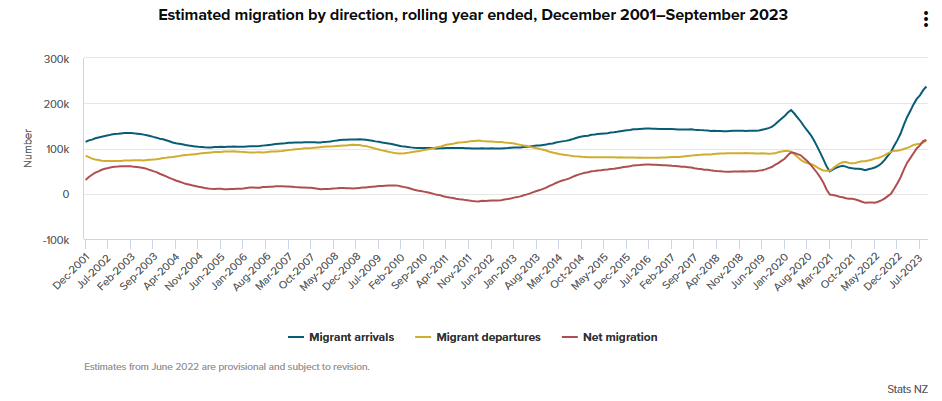

Like Australia and Canada, New Zealand is experiencing a record post-pandemic immigration boom, with net overseas migration a hitting an all-time high 118,800 in the year to September:

Source: Statistics New Zealand

Independent economist Tony Alexander noted last month that this 2.3% boost to New Zealand’s population “means upward pressure on rents and house prices because these people need about 43,000 extra houses to live in”.

David Hargreaves at Interest.co.nz is concerned that “rampant migration and an enlivened housing market could undermine efforts to get the economy on a sound footing”, as well as hamper the Reserve Bank with its inflation-fighting efforts:

“Are we going to keep expanding our population at this rate? And what happens if we do?”

“This for me is the ticking timebomb as we look towards the dawning of 2024. This for me is the number one issue by a mile for this country in the coming year and beyond”.

“The largely unknown factor is the extent to which the demand side of the migration ledger – be it for housing, infrastructure, services and you name it – will have adverse impacts on the economy, not least potentially through inflation”.

“The Reserve Bank, as controller in chief of inflation, had appeared sanguine, but then suddenly dropped that in its November Monetary Policy Statement in which every second word appeared to be either ‘migration’ or ‘population’.

“Clearly it is now getting worried about its inflation plans being swept away in the migration flood”.

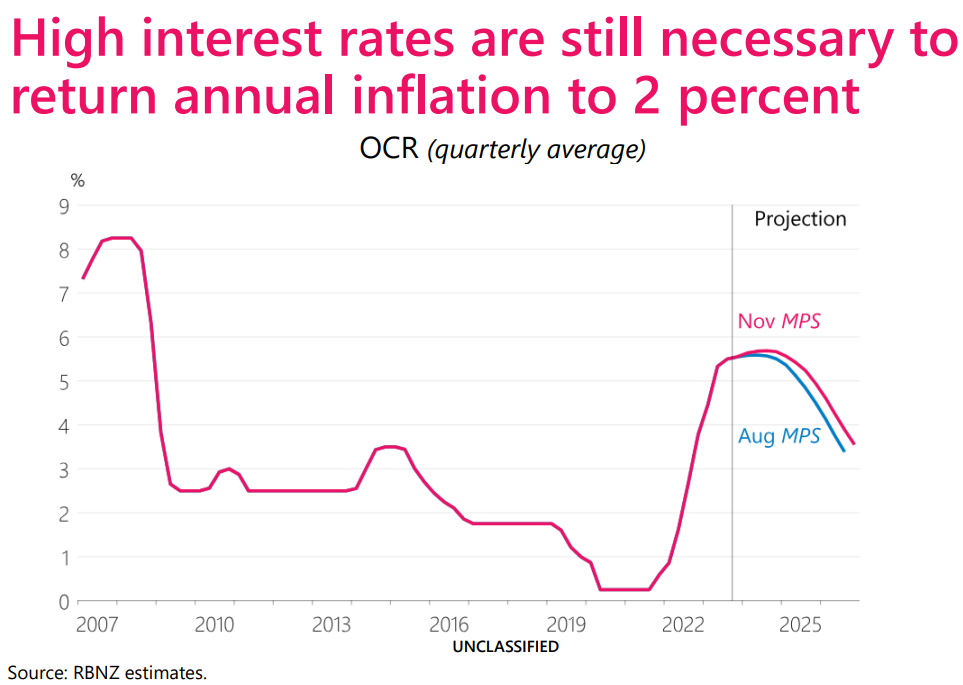

Indeed, this month’s Monetary Policy Statement from the Reserve Bank flagged that it will need to keep rates restrictive for longer amid persistently strong demand, caused in no small part by the record net overseas migration:

The Reserve Bank explicitly noted that “demand growth has eased, but by less than anticipated over the first half of 2023 in part due to strong population growth”.

“The OCR will need to stay restrictive, so demand growth remains subdued, and inflation returns to the 1% to 3% target range”:

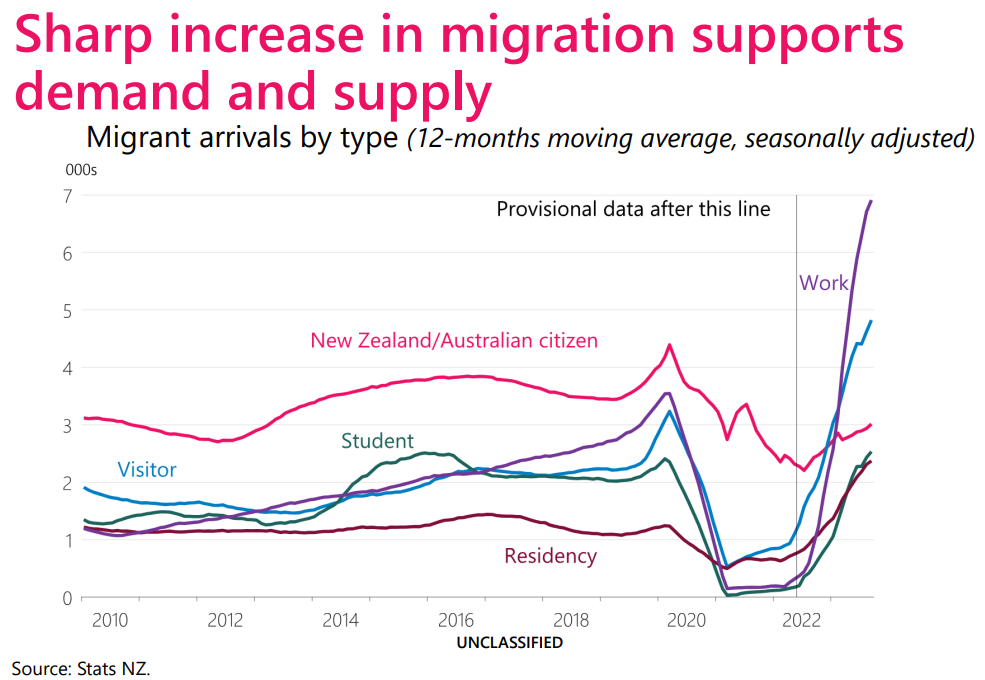

“The effects on aggregate demand are becoming apparent. This is increasing the risk of inflation remaining above target”.

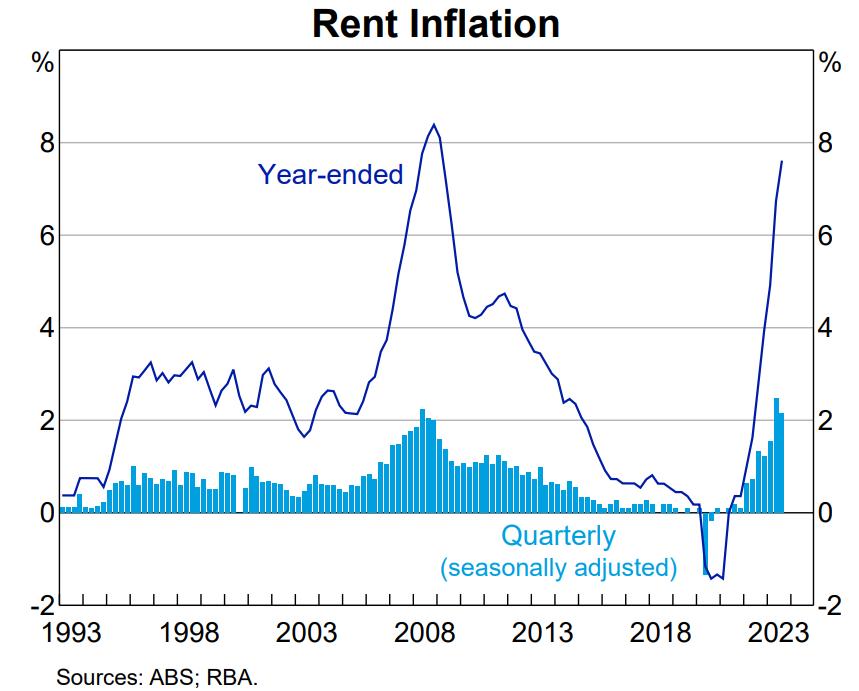

“Strong population growth has contributed to an increase in housing rents”.

“Rent increases, and any increases in construction costs in response to greater housing requirements, affect inflation directly, as rental prices and construction costs are accounted for in the consumer price index”.

“House price increases affect inflationary pressures indirectly, via higher household wealth and an associated increase in consumption”.

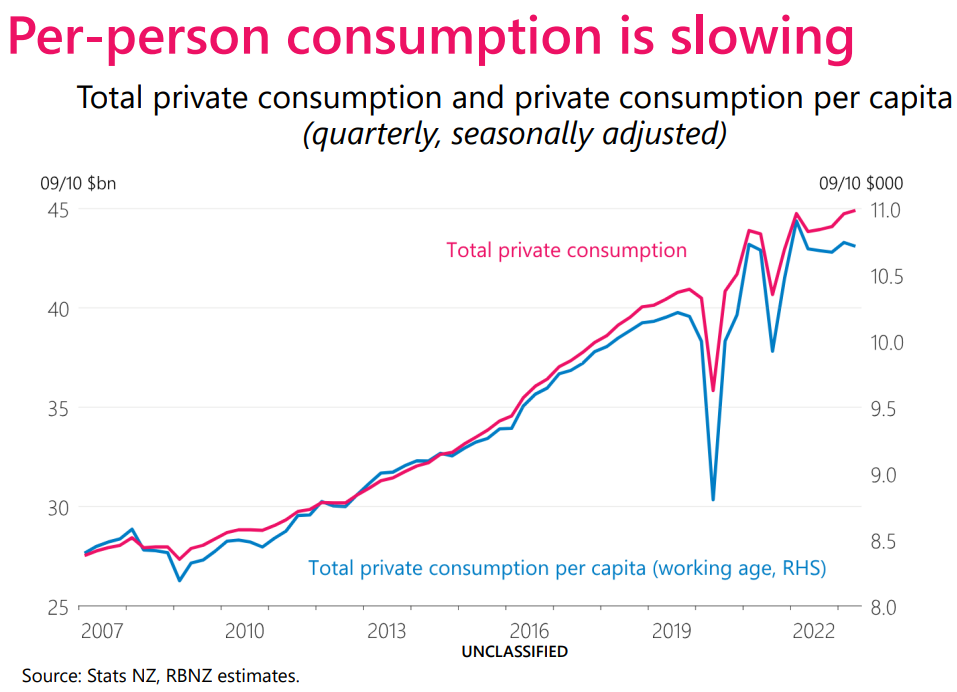

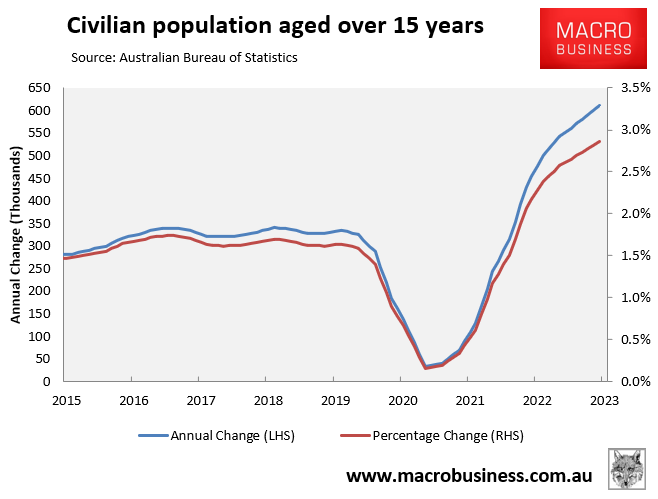

Australia’s Reserve Bank is in a similar predicament, with record growth in the number of households via immigration more than offsetting cutbacks in spending by individual households:

Accordingly, Australia’s aggregate demand has continued to grow in the face of aggressive monetary tightening and cutbacks in per capita spending.

The record migration flows have also pushed rent inflation higher, which is directly contributing to Australia’s stubbornly high overall CPI inflation:

Growing aggregate demand through record population growth inevitably means that both Reserve Banks must retaliate with higher interest rates to temper said demand growth.

Effectively, we have got immigration policies in both countries working at cross-purposes with the central banks’ restrictive monetary policies.

It is a lose-lose situation for workers in both countries, who suffer from falling real wages while their essential rent and mortgage costs are driven to the moon.