Gavkal with the note. It is hard to see this being anything but heavily disruptive to Chinese construction.

China Evergrande Group, the giant property developer whose financial travails have weighed on markets for two years now, is threatening to wreak even more damage to China’s real-estate sector and the broader economy.

The company has admitted the debt restructuring plan proposed in March is no longer feasible, and disclosed that its chairman under criminal investigation and that regulators are not allowing it to issue new debt. Even after that avalanche of bad news, there could be more to come: local media have reported that several other current and former executives, including its former CEO and CFO, have been questioned about alleged illegal fundraising.

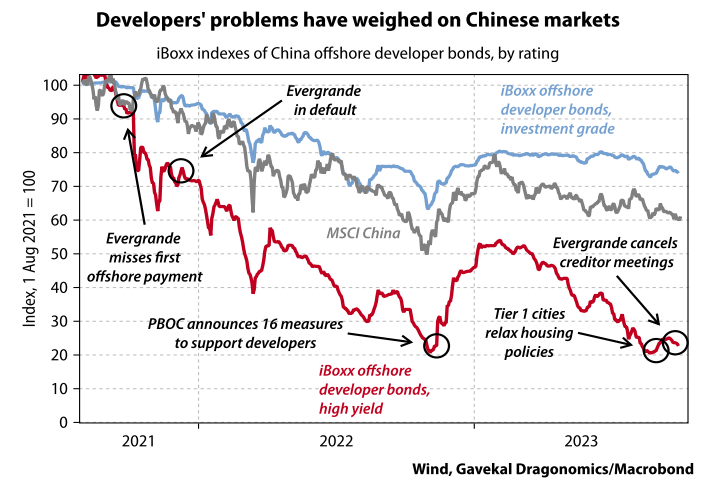

These recent events clearly increase the probability that Evergrande will face liquidation, which some offshore creditors are in fact pursuing. At the least, an orderly restructuring of what was once China’s largest property developer seems increasingly difficult to achieve. The implications of Evergrande’s troubles are broader than its direct creditors, as the recent pullbacks in equity and offshore bond prices attest. Investors have at least three reasons to be concerned about how the Evergrande situation plays out.

First, the chances of a government policy error that disrupts markets and the economy have increased. In mid-August, Evergrande’s primary onshore unit disclosed that it was under investigation by securities regulators for possible violations of rules on information disclosure. It was not until late September that Evergrande’s offshore-listed entity disclosed that, because it was under investigation, it could not issue new debt, which meant it could not complete its restructuring plan.

It’s not clear whether regulators deliberately torpedoed Evergrande’s restructuring, or whether that was an unintended consequence. But the probe does show regulators are not afraid of risking turmoil in the offshore markets. It does not mean that financial regulators are generally taking an aggressive stance and trying to drive property developers out of business; they have contained chaos in the onshore bond markets amid repeated developer defaults. Still, mistakes are always possible, and developers’ fragile finances make the flow of events difficult to predict or control.

Second, there is potential for additional damage to housing-market sentiment, which is already jittery. Housing sales have been stuck at depressed levels since April, and have not yet convincingly recovered despite policy changes that make finance for homebuyers much cheaper and more widely available.

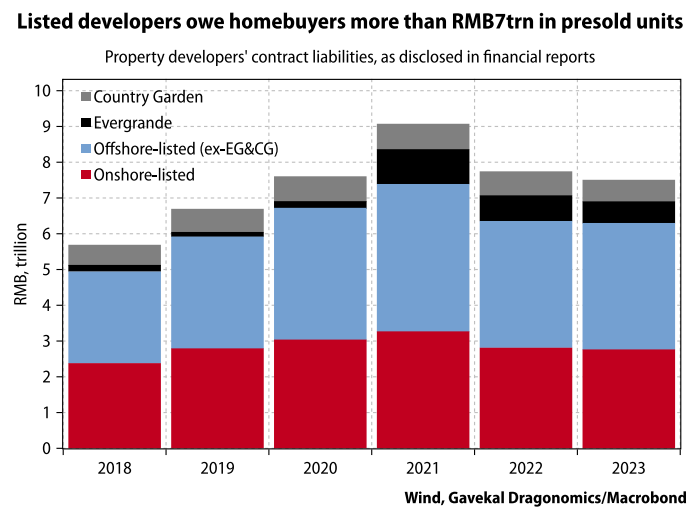

Evergrande’s highly publicized financial problems helped spark the collapse in property sales back in mid2021, as homebuyers started to worry it and other developers would not be around to complete the unfinished housing they had paid for in advance. Since then, Evergrande has claimed it is back on track delivering projects, but if it has to stop work once again, that could spook homebuyers.

The government has told banks to provide financing to ensure unfinished housing gets completed, but it’s not clear the funding available is sufficient to solve the problem. Evergrande reported contract liabilities (i.e., payments made in advance from buyers) of RMB604bn in its interim 2023 report, equivalent to around 600,000 units; Country Garden has another RMB603bn.

In total, offshore- and onshore-listed developers owe households RMB7.5trn in unfinished units, according to their 2023 interim reports. Developer troubles still have the potential to undo the tentative stabilization in housing sales since August.

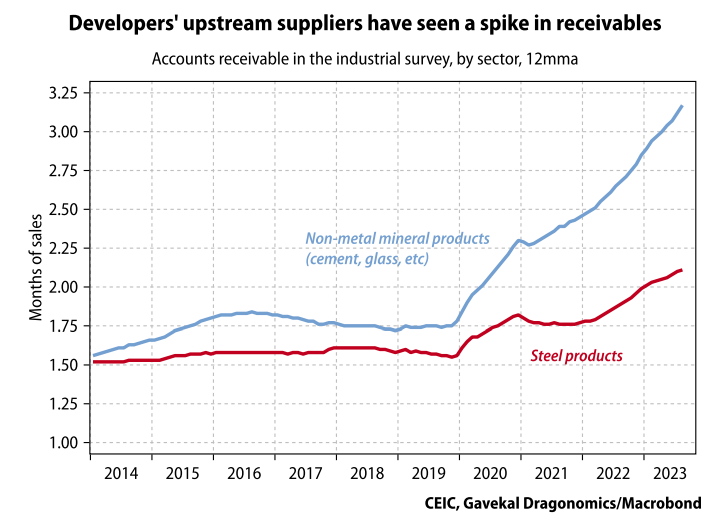

Third, the financial stress of property developers is spilling onto other companies as developers delay or default on payments to their suppliers. China’s listed developers collectively owe RMB3.4trn to in trade payables to their suppliers as of midyear 2023. Evergrande alone accounts for RMB602bn of those liabilities, and 81% of its trade payables are associated with invoices more than a year old.

As Evergrande has just RMB4bn of cash in the bank, it’s hard to imagine those payables will get paid in the near future. If its suppliers have to write off those bills, the hit to their balance sheets would be equivalent to about 0.5% of GDP.

The situation of other developers does not seem as severe: for instance, while Country Garden is also in trouble, the ageing analysis of trade payables in its 2023 interim report shows that only 1.5% are more than a year old. Yet even if most developers are still paying their suppliers in less than a year, there is evidence that the pace of payment has slowed significantly.

According to the industrial survey, aggregate receivables for the steel product sector and non-metal minerals sector (which includes cement and glass) have sharply risen, in terms of months of sales, since 2020. While firms in these construction-materials sectors have customers outside real estate, the most likely explanation is a delay in payments from cash-strapped developers.

For these industrial sectors alone, that stretching of receivables payment has tied up roughly RMB1trn in working capital, money they could be using to pay employees, invest in new equipment or retire debt. Comparable data on receivables is not available for the construction sector, but plausible estimates suggest delayed payments could be tying up another RMB2-3trn in their working capital. In short, the travails of China’s real estate developers have already sucked trillions of renminbi of liquidity out of the economy—and if things get worse for developers, so will the financial drag on related industries.