Blind Freddy can see that Australia’s governments have failed dismally to provide enough public housing for the nation’s ballooning population.

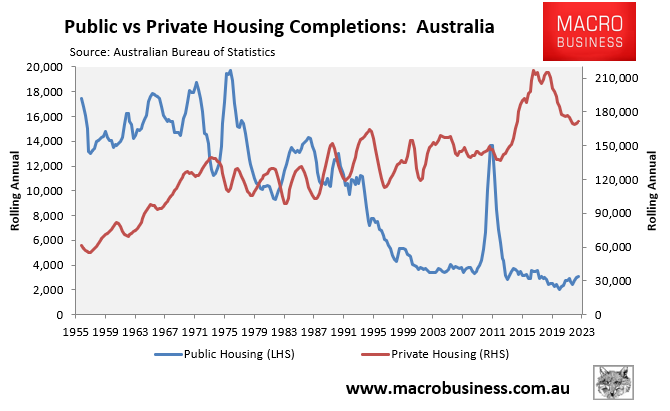

The following chart shows the disparity between the number of public and private sector housing completions in Australia over the course of a year:

Between the years 1955 and 1978, Australia constructed an annual average of 15,400 public housing units.

On average, 11,700 new public housing units were constructed each year between 1979 and 1990.

The average yearly production of new public housing fell to 8,000 from 1991 to 1999.

The number of public housing units created annually has decreased to around 4,000 so far this century.

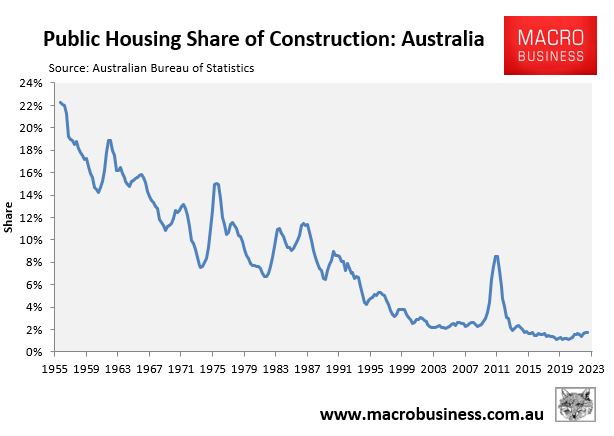

The situation is even worse when public housing construction rates are compared to the total number of newly built homes:

At the beginning of the series in 1955, public housing constituted 22% of total housing construction. This, however, had reduced to around 2% by the year 2022.

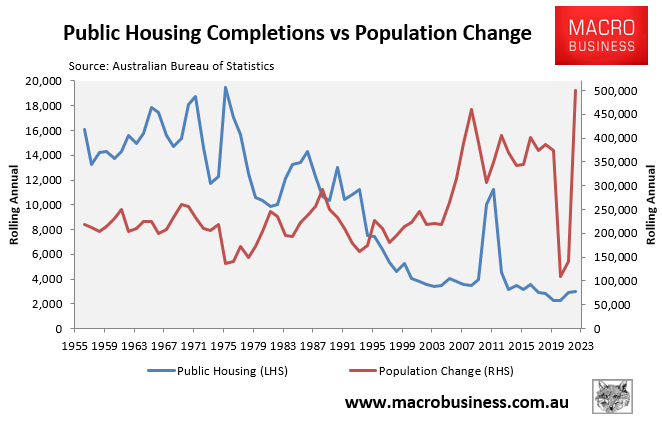

The federal government’s policy of mass immigration has increased Australia’s population by 7.3 million this century, but public housing development has fallen:

The following chart shows the relationship between the expanding population of Australia and the construction of public housing:

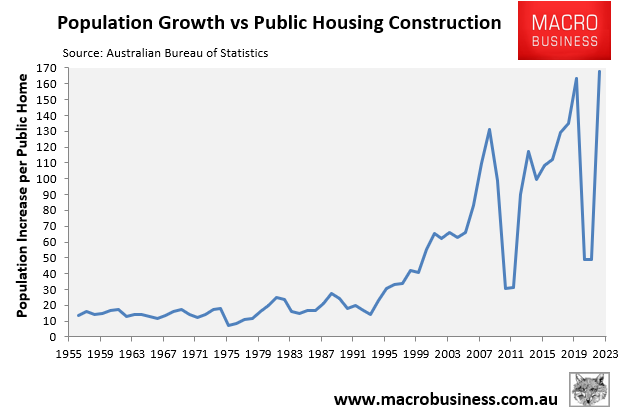

Approximately one public dwelling was constructed for every twelve to thirty new Australians between 1955 and 1993.

In 2022, there was only one publicly built dwelling for every 168 people who became residents of Australia.

The collapse of public housing construction and the influx of record numbers of overseas migrants are directly responsible for this decline.

Spokesperson for Everybody’s Home, Maiy Azize, said the nation’s record low rental vacancy rate proved “only the federal government can create affordable rentals for the people who need them, when and where they need them”.

“For years governments have been walking away from social housing, relying on the private sector to deliver affordable homes”, Azize said. “These numbers show that’s a dangerous approach”.

Azize has called on governments to create 25,000 social homes each year to solve the housing crisis.

“Australia’s social housing shortfall is massive. We need to create 25,000 new social homes across the country every year. We’re calling on the government to act now and end the shortfall for good”, she said.

Increasing social housing is obviously worthwhile and needed. However, expecting the construction of 25,000 social homes a year is delusional and would never occur. The financing costs alone would be enormous.

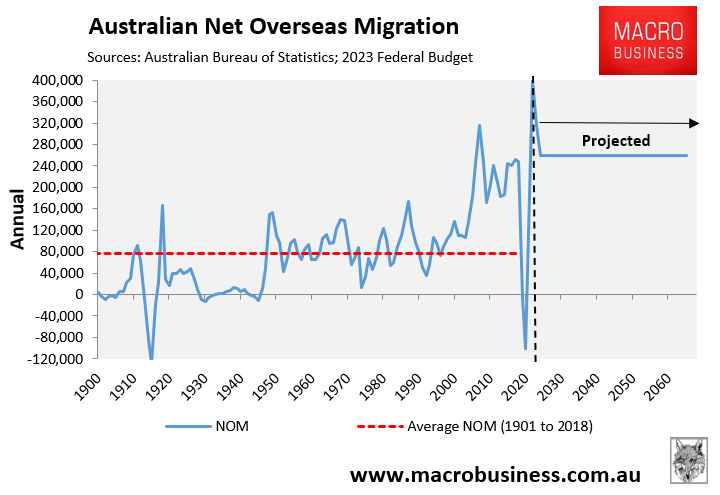

If it was serious about solving the housing crisis, Everybody’s Home would also call on the government to reduce housing demand by lowering immigration to sensible historical levels of around 100,000 a year:

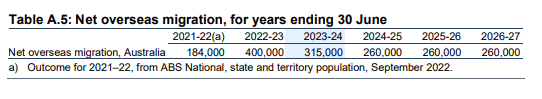

The federal budget projected 400,000 NOM in 2022-23, 315,000 NOM in 2023-24, and then 260,000 NOM between 2024-25 and 2026-27:

Source: 2023 federal budget

The latest Intergenerational Report also projected long-term NOM of 235,000 a year, which will grow the nation’s population by 14.2 million people over the next 40 years – equivalent to adding the combined populations of Sydney, Melbourne, Brisbane and Adelaide.

Australia will never build enough housing (including social homes) under such extreme immigration settings.

The Albanese Government also announced that it would lift Australia’s humanitarian migrant intake to a record high 20,000, en route to a planned 27,000 humanitarian intake a year.

Many of these humanitarian migrants will obviously require public housing, thereby making the shortage even worse.

Increasing immigration to record levels amid reduced investment in public housing is a recipe for disaster.

Australia, therefore, needs drastic cuts to immigration alongside more investment in public and social housing.