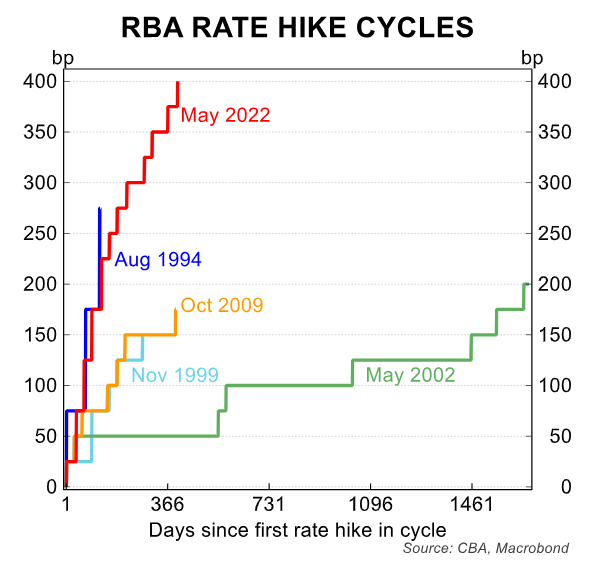

The Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) has raised the official cash rate by 4% in just 13 months, the steepest and largest monetary tightening in the country’s history.

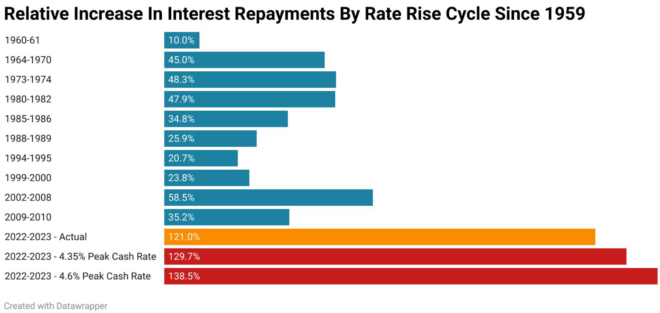

According to Tarric Brooker, an independent economist, the RBA’s rate hikes have increased mortgage interest repayments by an unprecedented 121%, which would rise to 138.5% if the RBA hiked rates two more times:

The suffering imposed on Australian mortgage borrowers is unparalleled in the world.

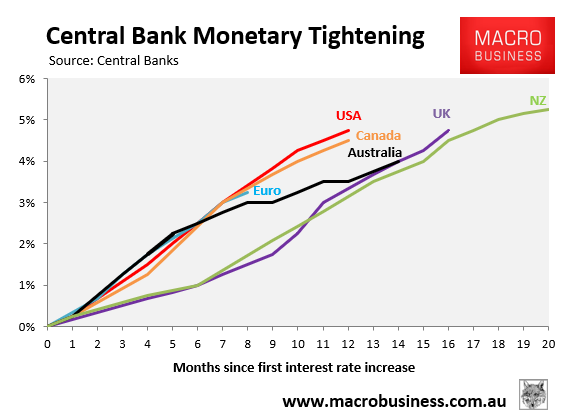

While the RBA has raised official interest rates less than other English-speaking central banks:

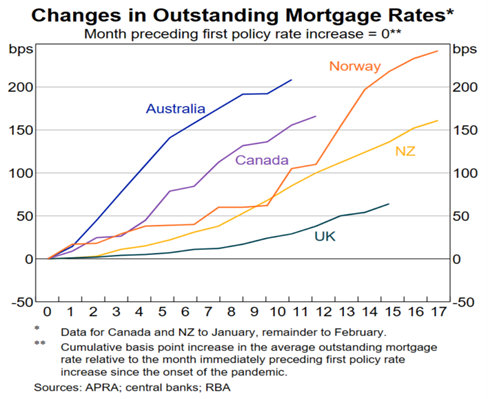

Because the majority of Australians have variable rate mortgages, the increase in average mortgage rates in Australia has been much higher:

According to the RBA chart above, as of February Australian mortgage borrowers had seen more than 200 basis points of mortgage tightening, which was much more than in other English-speaking countries.

The 4% increase in Australia’s official cash rate is well below the 5.25% increase in New Zealand’s official cash rate over this cycle.

Nonetheless, the RBA graphic above shows that average mortgage rates in Australia had risen by roughly 210 basis points, compared to around 160 basis points in New Zealand.

This is because the majority of home loans in New Zealand have fixed interest rates.

Mortgage rates in the United States are normally set for the entire loan term of 30 years, which is why the country isn’t even included on the RBA chart above.

In short, when official interest rates rise (or fall), mortgage holders in most other countries are not affected nearly as much as Australians.

Australian mortgage holders are being crushed by RBA:

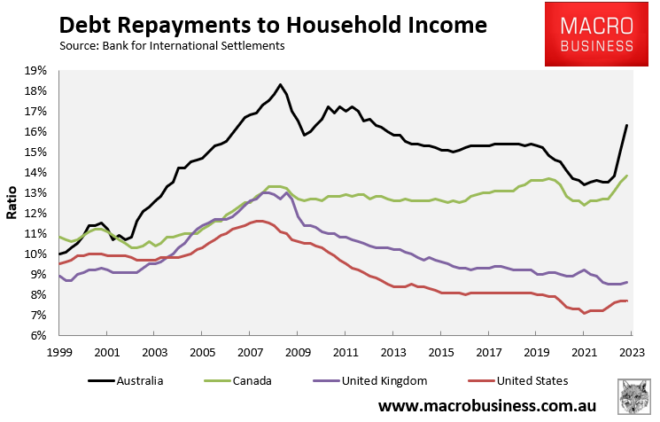

The Bank for International Settlements (BIS) publishes a series that compares aggregate debt repayments (principal and interest) to aggregate household disposable income in various nations.

According to the graph below, Australian consumers spent 16.3% of their disposable income on debt repayments at the end of 2022, up from 13.5% in the March quarter before to the RBA’s first rate hike:

The rise in debt payment expenses in Australia has likewise outstripped that of the other English-speaking countries studied by the BIS.

At the end of 2022, the official Australian cash rate was 3.10%.

As a result, the above chart excludes an additional 100 basis points of tightening, as well as the expiration of fixed-rate mortgages, which has boosted debt repayments further but is not represented above.

It is also worth noting that little more than one-third of Australian households have mortgages, which explains why just 13.5% of aggregate household income was committed to debt repayments at the end of 2022.

The impact on mortgage-holding households is, therefore, substantially worse.

Indeed, the impact of the RBA’s record monetary tightening has almost exclusively fallen on these mortgaged households, rather than the general population.

Brace for more mortgage pain:

The situation for Australian mortgage holders is only going to get worse from here.

First, the RBA is projected to raise interest rates more in the coming months, raising repayments.

The CBA’s economics team now anticipates another 25 basis point hike by the RBA in August to a top rate of 4.35%, with a possible further increase in July if data permits.

Westpac, ANZ, and NAB each expect the RBA to raise interest rates by 25 basis points in both July and August to a peak of 4.60%.

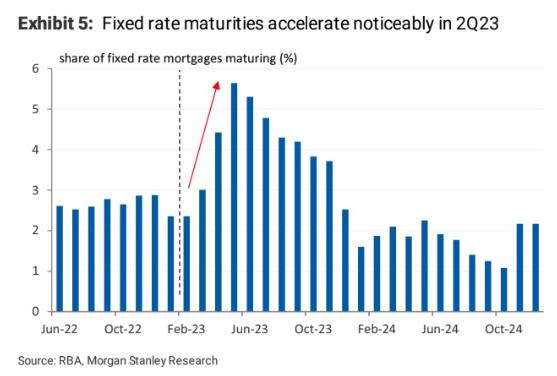

Second, over 500,000 fixed-rate mortgages will expire over the remainder of the year, meaning borrowers will reset from mortgage rates of around 2% to variable rates of around 7% (higher if the RBA continues to rise).

As such, average mortgage rates in Australia will continue to rise even if the RBA does not raise the official cash rate any further.

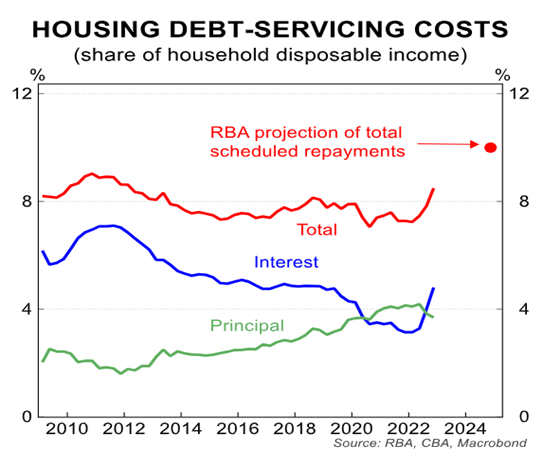

In this regard, the following chart from CBA’s economics team is useful. According to RBA projections, average mortgage repayments will reach an all-time high share of household income in 2024:

These repayments will easily eclipse what mortgage holders in other countries pay, making Australia the worst country in the world to have a mortgage.