This is an interesting take by Capital Economics. I don’t disagree. The next batch of SLOOS data is presented to the Fed this week and then released. It should show much tighter US lending standards.

The strongest headwind for the global economy has shifted from an energy crisis and the related squeeze on real incomes to a potential banking crisis and associated drag on credit. Since banks are relatively well-capitalised we do not anticipate a full-blown banking crisis, but we do expect a tightening of credit conditions to weigh on economic activity across the board. We still expect recessions in all major advanced economies later this year, but the shifting headwinds have meant that we no longer expect the US to be more resilient than Europe. With central banks still mindful of inflation risks, interest rates will stay at their peaks for several months. But when they come, cuts will be more aggressive than is typically assumed. Meanwhile, China’s reopening boost is now largely over and weak balance sheets and limited policy support will mean that the recovery is more likely to disappoint than surprise from now on.

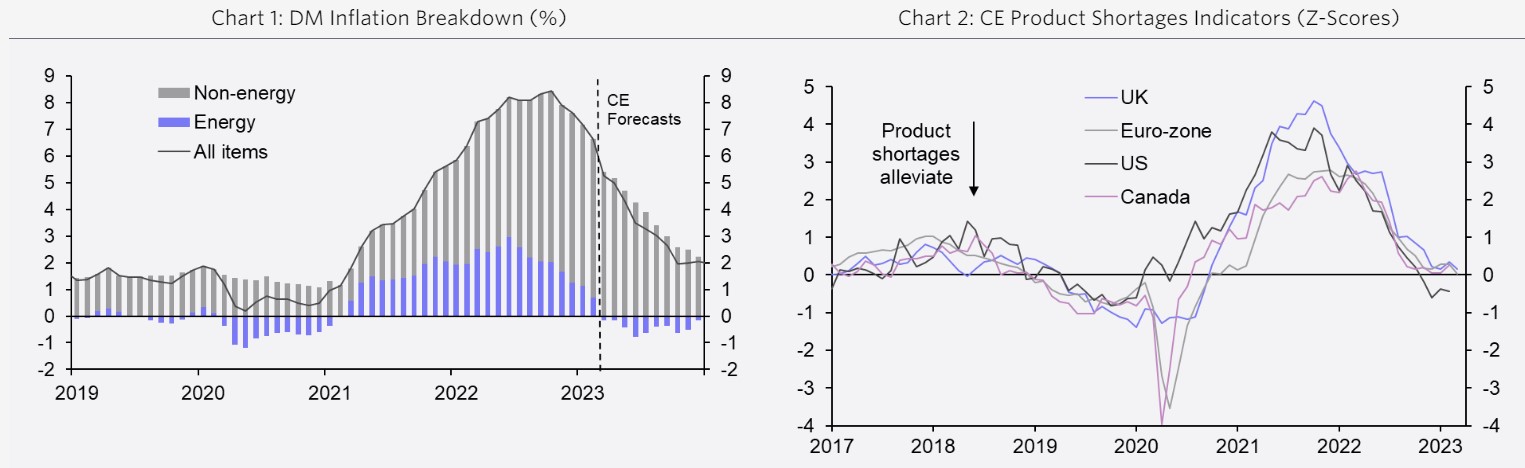

- The best news over recent months has been the fall in energy prices. We now expect gas and oil prices to end the year around 20% and 10% lower than we had previously anticipated. This means that energy will switch from a boost to a drag on inflation by the end of the year (see Chart 1), helping to ease the cost of living squeeze dramatically. The ramifications are particularly positive for Europe where the hit to real incomes has been greatest.

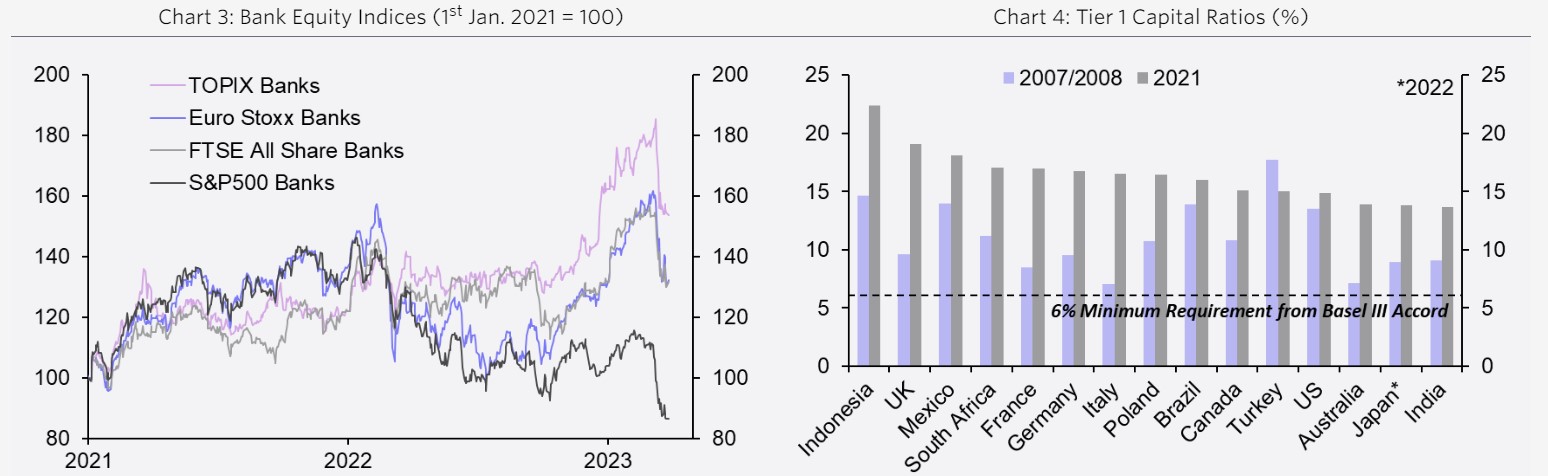

- The other upside surprise has been the resilience of activity in advanced economies, meaning that GDP started the year on a stronger footing than we had expected. This relates partly to the fact that supply shortages have become a non-issue. Our measure of product shortages suggests that they are back around ‘normal’ levels (see Chart 2), which will also contribute to lower inflation.

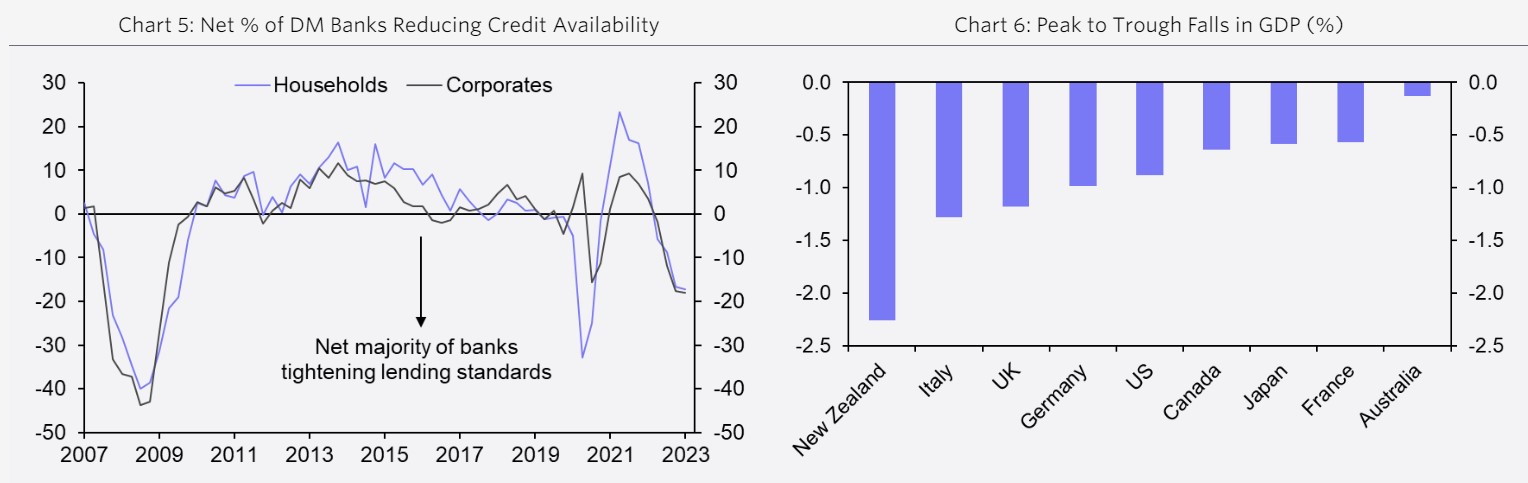

- But, at the same time, the lagged effects of previous policy tightening have begun to feed through as we had long warned that they would. The most prominent evidence of this has been in the banking sector, where the collapse of two US banks and forced takeover of Credit Suisse have raised fears about the health of banks more generally. (See Chart 3.)

- Points of reassurance are that banks are far better regulated than they were at the time of the financial crisis and they are generally much better capitalised as well, with Tier 1 Capital Ratios far above the regulatory minimum of 6% (See Chart 4.) So while there are downside risks around hidden exposures or a sudden loss of confidence and deposits, our sense is that a full-blown banking crisis will be avoided. Banks across EMs look relatively stable, and most EMs are now less exposed to foreign lending.

- Nonetheless, banks will tighten their credit criteria and rein in their lending, with adverse effects for firms and households. Indeed, they were doing this even before the collapse of SVB in March. (See Chart 5.) Interest rate-sensitive spending will weaken further and property prices could fall sharply.

- In the US, banking sector strains will precipitate a further significant tightening in credit conditions, making it more likely that the economy will fall into recession this year. But given the stickiness of inflation, we think that the Fed will wait until later this year before cutting interest rates.

- As in the US, the recent tremors in Europe’s banking sector will probably prompt a tightening of credit conditions, albeit not to the same extent as across the pond. Nonetheless, with the ECB likely to press on with rate hikes in the face of more stubborn inflation pressures, the euro-zone is also likely to contract this year.

- Like in the euro-zone, the plunge in natural gas prices will mean that UK energy prices are less of a drag on growth. But with two thirds of the effects of rate hikes yet to feed through, the UK will similarly enter recession.

- With the Japanese economy entering a mild recession and inflation likely to fall, the short-term policy rate will stay at -0.1%.

- China’s GDP growth is likely to exceed the government target this year following the country’s rapid re-opening. However, most of this rebound in activity is now behind us. And with weak balance sheets at home and weak demand overseas, combined with limited policy support, the recovery will shift down a gear later in 2023.

- For now, central banks are trying to separate financial stability risks from inflation risks, offering generous loans and swap lines to maintain liquidity while at the same time continuing to raise interest rates to stem inflation. This is understandable with labour markets still very tight and wage growth out of whack with their inflation targets.

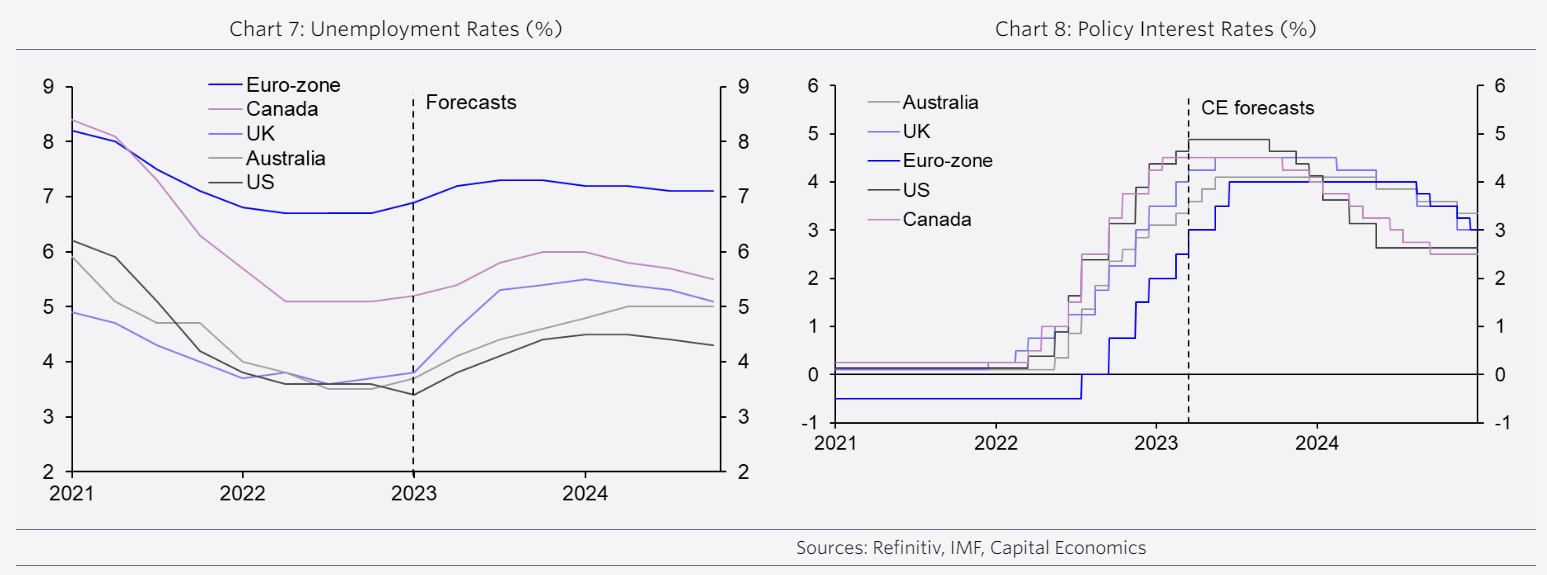

- But, in time, the ongoing impact of policy tightening is likely to drive major advanced economies into recession. (See Chart 6.) Once that happens, weak demand will help to pull underlying inflation down. Unemployment is likely to edge up too (see Chart 7), albeit by less than in previous recessions.

- So while interest rates will be held at their peaks for several months, cuts when they come will be sharper than most anticipate. EM central banks were ahead of the game in tightening and will be the first to loosen too. But interest rates in the US and UK will end next year far lower than markets expect, allowing an economic recovery to take hold. (See Chart 8.)