MB has argued for 18 months that Albo and Chicken Chalmers committed two monumental macro blunders upon their election, which delivered Australia a much worse inflation shock than it ever needed to be.

Failing to contain the Ukraine War fallout in energy markets and dropping an immigration bomb on housing were the main drivers of persistent Australian inflation in non-discretionary items such as utility bills and rents.

Were it not for these policy errors, rates would never have reached today’s peak and would already be falling.

This point is made abundantly clear in a terrific new note by Gareth Aird at CBA.

Non‑discretionary inflation is the primary driver of elevated inflation

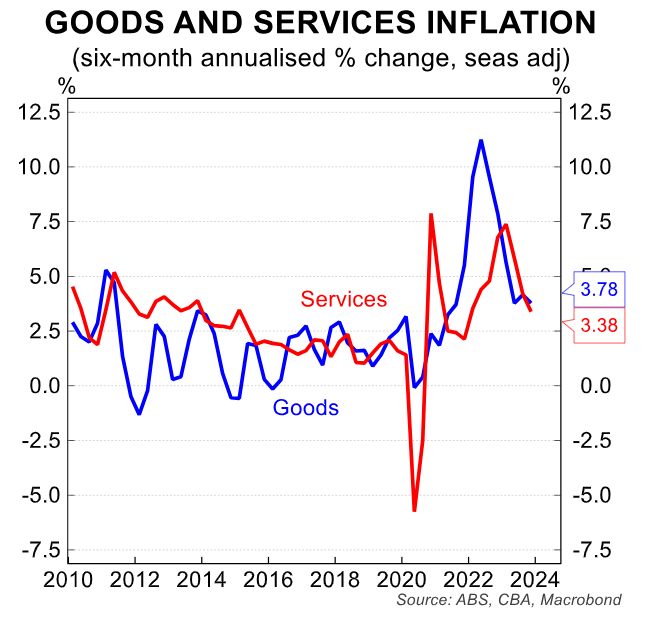

■ The recent inflation debate has generally centred on goods vs services inflation.

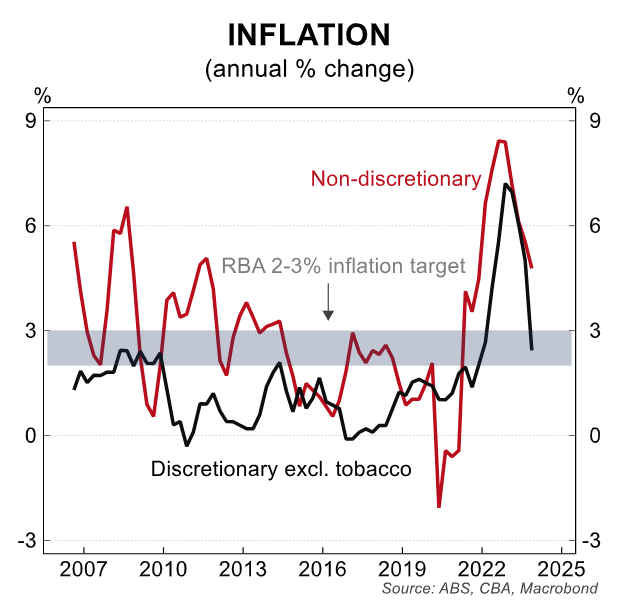

■ But the split between discretionary and non‑discretionary inflation more accurately captures the main inflation themes presently.

■ Inflation for discretionary goods and services (ex‑tobacco) has fallen to the mid‑point of the RBA’s target band.

■ In contrast, non‑discretionary inflation was a much higher 4.8%/yr in Q4 23.

■ Restrictive monetary policy has been successful in pulling down the rate of inflation for discretionary goods and services.

■ We believe the discussion on services inflation potentially becoming ‘sticky’ is overdone ‑ services inflation on a six‑month annualised seasonally adjusted basis is lower than goods inflation on the same measure.

Discretionary inflation has dropped as quickly as it went up

The inflation basket can be carved up a number of ways. The most conventional methods of slicing the CPI are by tradables vs non‑tradables inflation and goods vs services inflation.

Economists and policymakers like to focus on these splits as they help to better understand the drivers of inflation at any particular point in time. But they are not the only ways the CPI can be dissected.

A lot of the recent discussion on inflation has been on the goods vs services split. The RBA has been vocal on services inflation in particular.

The RBA Governor in a speech in November last year stated that, “inflation is being driven by domestic demand …. increasingly underpinned by services. Hairdressers and dentists, dining out, sporting and other recreational activities – the prices of all these services are rising strongly.”

In the February Statement on Monetary Policy it was noted that, “services price inflation in particular remains high, consistent with the assessment that there is excess demand in the economy and strong domestic cost pressures”.

We think that the focus on goods vs services inflation misses the more important elements of the current drivers of inflation. And we think that concerns over services inflation proving to be a little ‘sticky’ are misplaced.

Instead, we believe the more useful split of the CPI to better capture the inflationary story is by discretionary vs non‑discretionary inflation (ex‑tobacco[1]).

On that score, we observe that discretionary inflation (ex‑tobacco) has slowed to 2.4%/yr (1.8% on a six‑month annualised basis). In contrast non‑discretionary inflation was a much higher 4.8%/yr in Q4 23 (4.0% on a six‑month annualised).

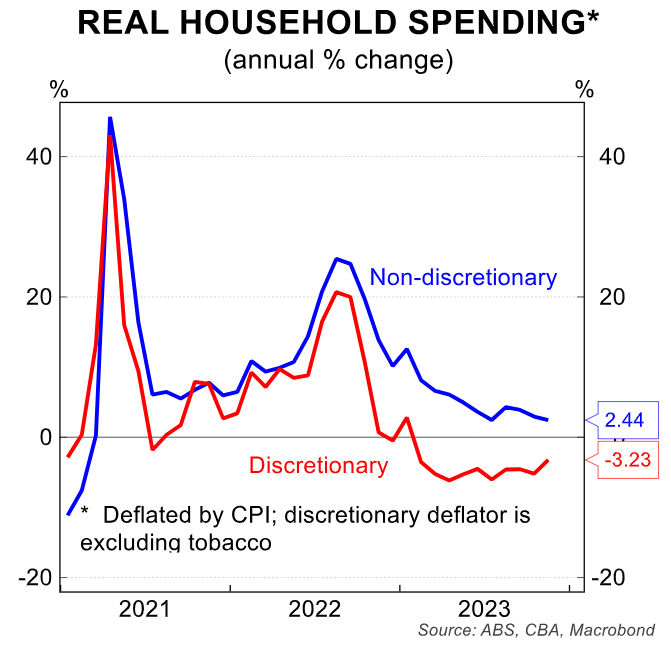

The upshot is that discretionary inflation should not currently be a concern for policymakers. The impact of monetary policy tightening as well as a lift in tax payable has weighed on household disposable income and by extension reduced demand for discretionary goods and services. As a result, inflation in the non‑essential space has fallen significantly.

To be clear, discretionary inflation lifted sharply in 2022/23. But it has retraced just as swiftly. Prices for non‑essential items made a sharp levels adjustment upwards when demand in the economy was strongest. But the lift in prices has not continued as demand has softened.

In contrast, non‑discretionary inflation remains quite elevated. It has primarily been a tale of four expenditure items; the cost of building a home (good), rent (service), electricity (good) and insurance (service) – see facing chart. These are all housing related.

Monetary policy has not been able to put downward pressure on these expenditure items. More specifically:

(i) The cost of building a home has risen sharply because of a lift in labour costs and energy‑intensive materials. Ongoing capacity constraints in the construction space, in part because of big public works programs to keep up with strong population growth, have pushed up the cost of home construction.

(ii) Rental inflation has been driven higher by the large mismatch between the underlying demand for housing (i.e. very strong population growth) and constrained growth in home supply. Rental markets are extremely tight across the capital cities and vacancy rates are at record lows. Commonwealth rent assistance has lowered rental price inflation a little, but it is still running well ahead of the overall level of consumer price inflation.

(iii) Electricity prices have risen significantly because of higher average wholesale costs. There has been a partial offset from energy rebates offered to households under the Australian Government’s Energy Price Relief Plan and various state government measures.

(iv) Insurance prices have been driven sharply higher by a large increase in premiums for house insurance. The big lift in the cost of building a home over the past two years as well as natural disaster costs have generated a commensurate lift in insurance premiums. As the RBA Governor said on Tuesday, “the insurance sector has its own issues going on and there’s not a lot that monetary policy can do about that …that’s much more a matter for the government”. We completely agree.

Recent services inflation data is encouraging

A look at services inflation on a seasonally adjusted six‑month annualised basis is particularly encouraging (see facing chart). The pace of services inflation on that measure is lower than goods inflation (3.4% for services vs 3.8% for goods).

We are comfortable with our call that services inflation won’t prove sticky, particularly as demand continues to cool and the labour market further loosens. Indeed we expect both goods and services inflation to dissipate a little more quickly than the RBA anticipates.

There will be pockets of both goods and services inflation that prove a little sticky because monetary policy is unable to directly influence price changes for some non‑discretionary components of the basket – particularly those influenced by strong population growth. But overall we expect ongoing disinflation to be the key theme in 2024.

We continue to expect the RBA to commence and easing cycle in September (we have 75bp of rate cuts in our profile in late 2024 and a further 75bp of easing in H1 25, which would take the cash rate to 2.85%).

I still expect sooner as Albo panics about Alboflation and delivers subsidies.