So says Gareth Aird at CBA. I agree.

- We forecast GDP growth to be 1.4%/yr at Q4 23 and to continue to run below‑trend through 2024 to be 1.6%/yr in Q4 24.

- Recession is not our base case, but a quarterly contraction in economic activity in 2024 is a distinct possibility. Indeed we forecast the 2023 per capita recession will continue until H2 24.

- We expect the annual rate of inflation to be 4.2% in Q4 23 and to decline to 3.0% by end 2024 (our forecast is for underlying inflation to be 2.9%/yr in Q4 24).

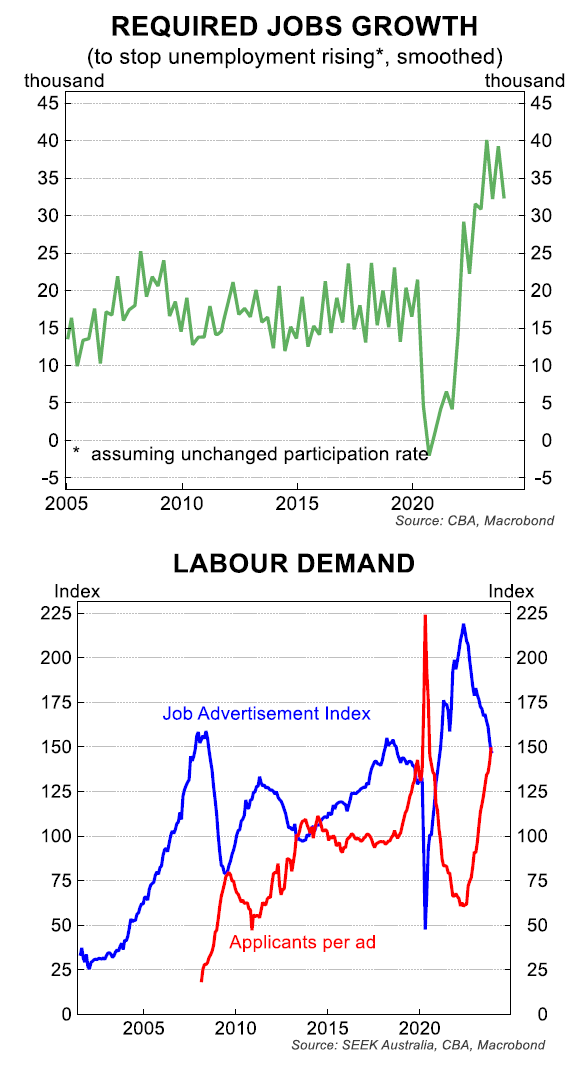

- The unemployment rate will grind higher over 2024 and we anticipate it will end the year at 4.5%.

- We retain our call that national home prices will lift by 5% over 2024.

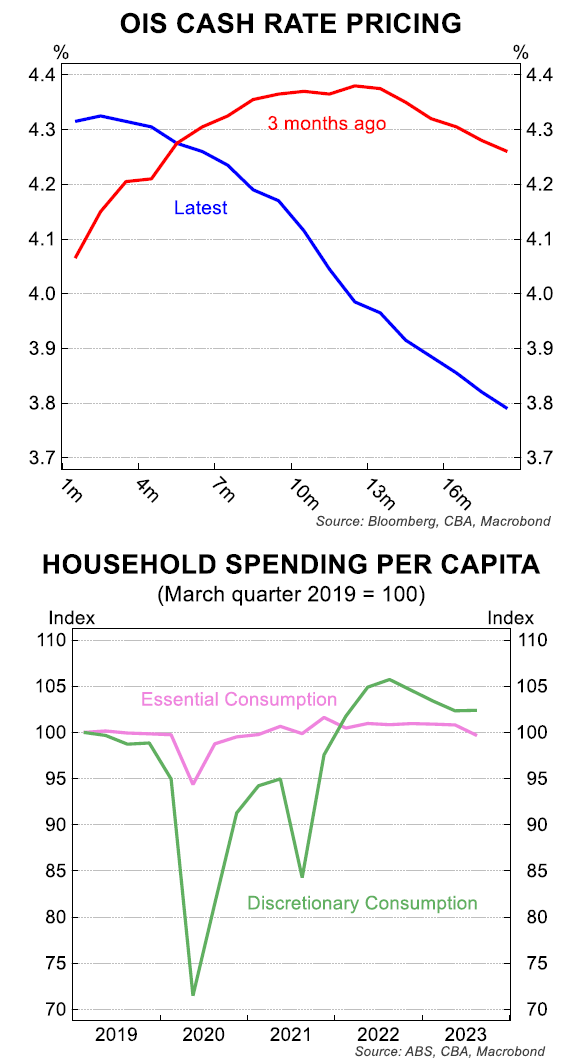

- We expect no further increases in the cash rate. We continue to expect an easing cycle to commence in September 2024.

- We have 75bp of rate cuts in our profile in late 2024 and a further 75bp of easing in H1 25, which would take the cash rate to 2.85%. We have monetary policy on hold in H2 25.

- Monetary and fiscal policy are the key uncertainties – the path of the cash rate from here will play a key role in determining economic outcomes in 2024. Fiscal policy also has the capacity to shape the trajectory of the economy.

- Momentum in the Australian economy slowed materially over 2023. GDP growth was below trend. And the economy was in a per capita recession over the year (latest data available is to Q3 23).

The quarterly changes in real GDP over 2023 read 0.5%, 0.4% and 0.2% (latest). The December quarter outcome will be published on 6 March ‑ we expect another soft outcome (see page 3).

Regular readers will know that we anticipated a marked slowdown in economic activity in 2023. But it took some time for that picture to emerge in the data.

We made the case through last year that the RBA’s highly aggressive policy tightening would be successful in slowing demand growth in the economy. And that economic growth would soften more materially than the RBA expected.

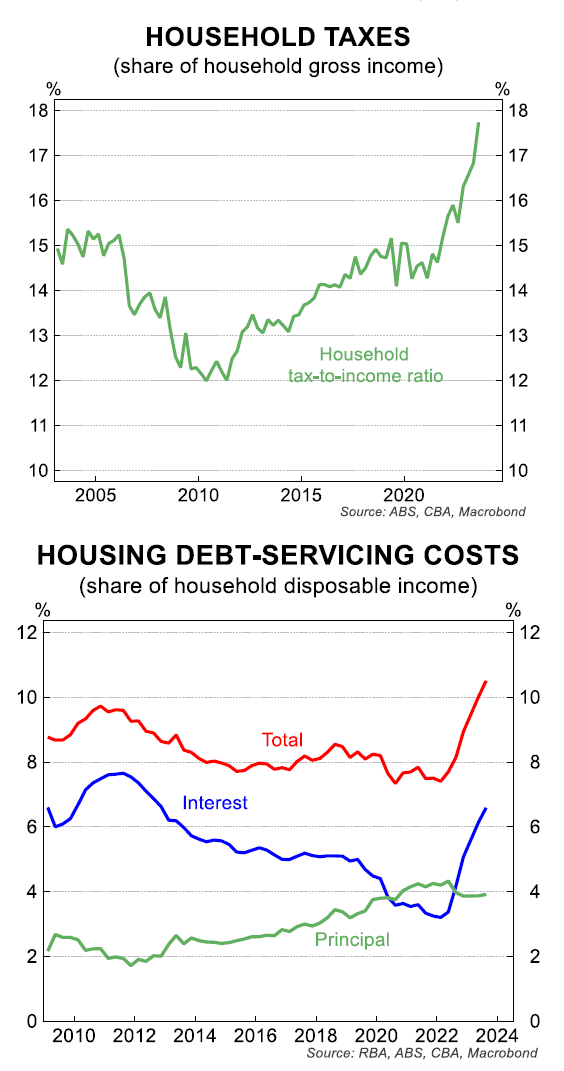

We maintained that the RBA did not need to raise the policy rate as high as many of the other major central banks because the transmission channel to mortgage holders is much more direct (see facing chart). In addition, Australian households are more highly leveraged.

The Q3 23 national accounts were arguably the first major piece of evidence that indicated our call for a pronounced slowdown in growth was the right one. The latest official inflation data revealed the slowdown in economic growth is having the desired impact on inflation (see here). And while the labour market has taken time to loosen, a clear upward trend in the unemployment rate has been established.

In summary, we believe the domestic economic data released over the last few months is consistent with our view that rate cuts are more likely than not in 2024. And since the Q3 23 national accounts printed in early December markets have moved in a direction that supports this view.

The impact of the RBA’s highly aggressive hiking cycle is best evidenced in the softness in household consumption. Real household consumption was just 0.4%/yr in Q3 23. Against the backdrop of ~2.5%/yr population growth there has been a big contraction in the volume of spend per person.

The change in consumption at the individual level is what a household feels. The movements in spending at the aggregate level is generally what the commentariat focuses on.

The weakness in the recent data on consumer spending in the national accounts would have surprised the RBA. For context, the RBA forecast real household consumption to be 1.1%/yr in Q4 23. For that outcome to materialise the volume of consumer spending would need to increase by a large 0.9%/qtr in the December quarter. A flat or small increase in spend in Q4 23 looks most likely.

The story on the consumer from a policy tightening perspective has been a simple one: rising mortgage repayments due to rate hikes take money out of the economy that would have otherwise been available for consumption. Higher rates also reduce the demand for credit (both housing and personal).

That said, the slowdown in consumer spending is not just an RBA‑induced one. The impact of monetary policy tightening on consumer spending has been amplified by a lift in tax payable along with the effects of elevated inflation.

Distribution also matters. The economic pain of a slowing economy has not been evenly felt. CBA data indicates that younger Australians have, on average, felt the economic pain a lot more than the older cohort of society (see facing chart).

While last year was a tough year for many Australian households, the news was not all bad. The annual rate of inflation declined to be 4.3% in November. And despite a per capita recession, the labour market was tight and wages growth lifted to ~4.0%/yr; a level broadly consistent with the inflation target.

The upshot is that the RBA’s objective of achieving a ‘soft landing’ remains alive. This essentially means returning inflation to target, while keeping the jobless rate from rising much above the non‑accelerating inflation rate of unemployment (NAIRU). We put the NAIRU at ~4¼%.

We believe the RBA can achieve the desired ‘soft landing’. But it will require policy decisions to be forward looking as we move through 2024. More specifically, we think the RBA will need to cut the cash rate even with inflation still above the target band to avoid the unemployment rate from lifting materially above 4½%.

Such a move can be justified because inflation is a lagging indicator. And the annual rate of inflation is a function of four quarterly changes (or twelve monthly changes). Base effects mean that the annual rate of inflation will sit above the target range through 2024. But our working assumption is that a six month annualised pace of inflation that is close to target would be sufficient for the Board to ease policy in an environment of rising unemployment and disinflation.

While the near term risk sits with another 25bp rate hike at the February Board meeting, we see the RBA on hold. We continue to expect an easing cycle to commence in September 2024. We have 75bp of rate cuts in our profile in late 2024 and a further 75bp of easing in H1 25, which would take the cash rate to 2.85%.

We believe the risks to our RBA call for an easing cycle to commence in September are broadly balanced (i.e. we assess the probabilities of policy easing before or after our September base case to be similar). For context, the market has ascribed a ~50% chance of a 25bp rate cut by July, which looks fair to us.

The RBA is likely to stick with a tightening bias until the Board is absolutely convinced that further rate increases are not required to return inflation to target. This means we expect the RBA to retain a tightening bias until at least the May Board meeting (recall that the RBA meeting schedule moves to every six weeks from February as compared with the previous eleven meetings per year).

Maintaining a tightening bias also allows the RBA to ‘jawbone’ the household sector to elicit a greater behavioural response to the already delivered rate increases.

In any event, the Board can shift from a tightening bias to an easing one followed by rate cuts over a short period of time if the data makes the case. Indeed we do not expect the RBA to communicate the prospect of rate cuts until shortly before the commencement of an easing cycle.