Capital Economics with the note.

China is not suffering a balance sheet recession: most private firms are not highly indebted and would borrow if they had more confidence in the economic outlook. But there are other parallels with Japan’s circumstances in the 1990s that point to difficulties ahead.

Comparisons are often drawn between China and Japan as it entered its “lost decade”. The latest focus on the huge expansion of corporate credit in China in the past 15 years, which has been even bigger than that in Japan in the 1980s, and the fact that credit growth has slowed recently – to a record low last month – despite easing from the PBOC.

For some, this is starting to look like the “balance sheet recession” that Japan entered in the 1990s following the bursting of credit-inflated bubbles in equity and property markets. In a balance sheet recession, indebted firms are unwilling to borrow even at low interest rates because they are concentrating on paying down debt. That makes monetary policy ineffective.

But China doesn’t resemble 1990s Japan in three important ways. Together these signal that most private firms won’t be needing to repair holes on their balance sheets over the next few years.

First, while Chinese equity prices have fallen substantially (onshore markets are down a third from their peak), land and property prices have not fallen anything like as far as they did in Japan.

And they are very unlikely to do so given that valuations aren’t as inflated and, crucially, that local governments operate administrative controls over prices – for example, by setting local price floors per square metre. Since prices can’t adjust, the property market is correcting through a sharp fall in land and property sales, which means the impact is mainly felt by developers and local governments.

Second, China’s corporate sector doesn’t have the cross-holdings that in Japan amplified both the run-up in asset values and the collapse. The cross-holdings meant that most large Japanese firms had significant indirect exposure to the equity and property markets on top of their direct exposure. In China, indirect exposure to troubled developers, for example, should be low.

Third, and most important, only a subset of China’s firms were able to participate in the credit boom. Much of the credit was extended to firms that are state-owned or controlled, such as local government financing vehicles. These firms will only de-leverage if the state instructs them to do.

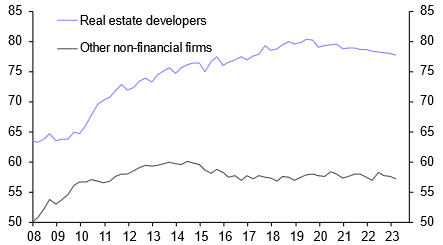

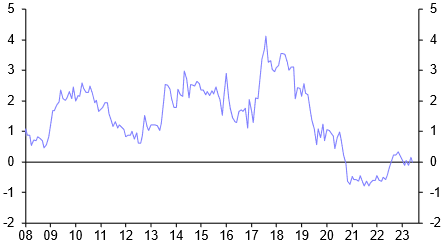

Within the private sector, borrowing has been dominated by property developers. Indeed, among listed firms, developers account for all of the run up in debt relative to assets since 2010. (See Chart 1.) Developers have been deleveraging since the Three Red Lines were imposed. (See Chart 2.) But other private firms aren’t overburdened with debt and so have no pressing need to focus on paying it back.

That’s only a partial relief though. Evidently private firms are currently unwilling to borrow (and invest) for other reasons: most likely, a lack of confidence in the immediate outlook for the economy.

And there are other parallels that can be drawn with Japan in the 1990s: the most obvious is around demographics: a falling working age population from 1994 contributed to the slower growth that has since made dealing with high debt harder. China’s working age population is also now falling.

But perhaps the most concerning parallel is in how Japan’s ill-fated credit boom had its roots in a failure to realise that trend growth had slowed. An investment and export-intensive growth model was running into diminishing returns and underlying productivity growth had slowed as the country approached the technological frontier. Rising asset prices and credit-fuelled activity allowed policymakers and companies in Japan to convince themselves through the late-1980s that the boom years were continuing. This made dealing with the inevitable slowdown harder when it arrived.

In China too, in our view, the fundamental drivers of growth have been deteriorating over recent years. Investment is no longer a reliable means to boost output. Trading partners are pushing back at China’s export sector even harder than Japan’s did in the 1980s. And productivity growth has weakened more than many expected – not in China’s case because it has reached high income but because of shifts in the leadership’s policy priorities.

Through this period, policymakers in China have resorted repeatedly to bursts of borrowing by state-linked firms and property developers to prop up activity. Even if a balance sheet recession is not the result, the resulting high levels of distressed debt will make the ultimate adjustment to slower growth harder to manage.

Talk about not taking “yes” for an answer.

China is Japan on steriods.