Westpac with a balanced take on the Budget.

The 2023 Budget is set against the backdrop of high inflation and sharply higher interest rates, with the RBA responding to the greatest inflation challenge in a generation. Currently, the unemployment rate at 3.5% is the lowest level in almost 50 years and commodity prices are around historic highs. Household incomes are under intense pressure from higher prices, rising debt servicing costs and additional taxation payments. The Federal budget has received an economic windfall from stronger incomes, some of which the Government is using to provide cost of living relief for the most vulnerable households. The outlook is challenging, with output growth set to slow as higher interest rates bite.

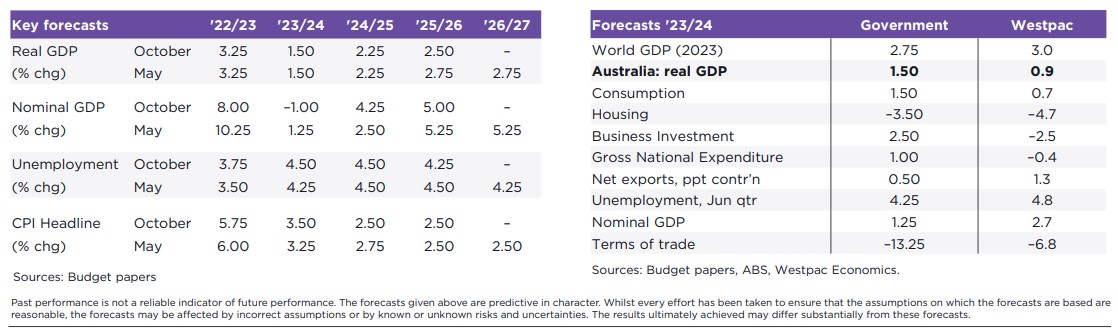

Budget deficit path revised lower

The budget deficit profile has been revised lower reflecting the windfall from stronger incomes (higher inflation and higher commodity prices) and from ongoing labour market strength, and after incorporating the cost of new spending initiatives. The cumulative deficit for the four years 2022/23 to 2025/26 is reduced to $81bn, down from $182bn in the October Budget, an improvement of $100bn.

For 2022/23, the budget position has improved by $41bn to be a wafer thin surplus of $4.2bn, representing 0.2% of GDP. The last time the budget was broadly in balance was immediately before the pandemic, in 2018/19. The surplus is a one–off, with the budget returning to deficit in 2023/24, a forecast $13.9bn (which respresnts a $30bn improvement on the October forecast). The deficit widens to $35.1bn in 2024/25 and to $36.6bn the year following, representing –1.3% of GDP in both years.

Budget windfall

The “stronger economy” delivers a budget windfall of $121.5bn across the four years to 2025/26, centred on a $112bn increase in revenue. Payments are somewhat lower, $10bn below the October forecast. Note, that there is a $13.9bn undershoot of payments in the 2022/23 year. Thereafter, payments are higher, with escalating costs of existing programs included in “parameter variations”.

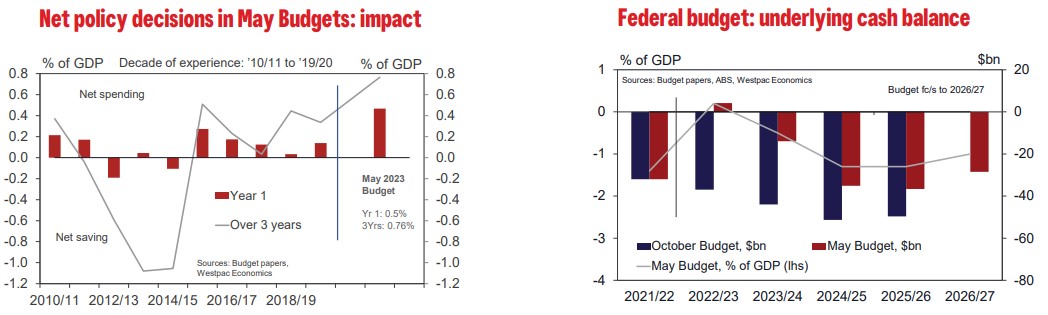

New policy

The government has increased spending, with a focus on cost of living relief. Net new policy costs $12bn in 2022/23, representing 0.5% of GDP, and over the three years to 2025/26 costs $20bn, representing 0.76% of GDP. By historical standards, this is a relatively expansionary budget. The experience over the decade prior to the pandemic was that the year 1 impact of new policy was around 0.25% of GDP (or less) and the impact over 3 years was 0.5% of GDP (or less).

Cost of living relief includes rental assistance and energy price relief – two measures which have an initial impact of lowering out of pocket expenses of households and thus lowering measured Consumer Price Inflation. New policy measures also span health and aged care. There are a number of tax increases to help pay for additional spending. See pages 2 and 3 for additional detail on initiatives and budget themes.

Payments remain above long–run average, after 2022/23 dip

Payments as a share of the economy, having been very elevated during the pandemic, dip to 24.8% of GDP in 2022/23 (benefitting from the stronger labour market) and then snap back to above 26% of GDP thereafter, which is well above the pre pandemic long run average of 24.9%. Revenue as a share of the economy remains elevated in 2022/23 at 25.0% of GDP, then is forecast to hold above 25% of GDP thereafter.

Debt profile lowered

Federal debt profiles have been lowered materially reflecting the improved budget position and lower long term bond rates (see chart on page 6). Net debt is now forecast to lift from an estimated 21.6% of GDP at June 2023 to a still modest 24.0% of GDP in 2025/26 (downgraded from 28.5% of GDP in the October Budget). Gross debt rises from an estimated 34.9% of GDP at June 2023 to a peak of 36.5% of GDP for 2025/26 (downgraded from 43.1% of GDP for 2025/26 and a peak of 46.9% in 2030/31).

Risks

The are a number of risks to the fiscal projections – both upside and downside. The risks to the view on national income are potentially tilted to the high side given that commodity price assumptions are still cautious, notwithstanding the adoption of a somewhat longer glide path down from current levels to “target prices”.

Downside risks relate to the potential for a more significant labour market downturn and to the output growth outlook, with the possibility of a “hard landing” domestically and globally triggered by aggressive tightening of monetary policy, with the risk that inflation proves more persistent. The other key downside risk to the fiscal outlook relates to the ongoing upward pressure on expenditures, particularly in the caring economy (health, aged care, the NDIS).

I will only add that the Budget has confirmed the outlook for a per capita recession in the forthcoming financial year with population growth running far in excess of 1.5% GDP.

It will be touch and go the year after as well if Albo persists with his lunatic Huge Australia drive.

Welcome to your new lost decade.