Independent economist Tony Alexander believes that the Reserve Bank of New Zealand has gone too far with its monetary tightening and has driven a sharp rise in unemployment.

I argued similarly on Wednesday.

Below is Tony Alexander’s report on the latest labour market figures.

Labour market weakens

The main data focus this week for those of us examining the state of and prospects for the New Zealand economy was the set of labour market data released by Statistics NZ Wednesday.

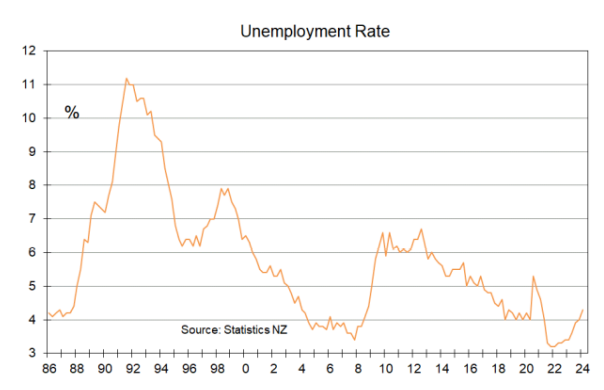

There had been universal expectations of a rise in the unemployment rate from 4.0% in the December quarter and this was the case with a rate of 4.3% recorded for the March quarter.

This takes the rate back to where it was early in 2021 but is still below the 5.3% recorded mid-2020. Just before the pandemic the unemployment rate was 4.0% and over the past three decades the rate has averaged 5.3%.

So in an historical sense 4.3% is not bad. But the trend is up.

The rise in the unemployment rate to 4.3% came about as the labour force grew 0.1% but the number of people in work fell 0.2%. This 0.2% decline followed 0.4% growth in the December quarter and no growth in the September quarter.

It seems okay to say that job growth in the New Zealand economy stopped in the middle of 2023.

Why has the labour market weakened? Because monetary policy was belatedly and aggressively tightened over 2021-23 as the Reserve Bank fought 7.3% inflation created by the excessively loose financial conditions they created during the pandemic.

Their management during that time in hindsight can be considered a failure but unfortunately the price of their poor decisions is borne not by anyone at the RBNZ but by householders with debt and especially those who bought a property late in 2021.

At least exporters this time around have been spared the horror which tended to be inflicted on them in past policy tightening periods. But that is only because interest rates have also been raised sharply in other economies in response to their own pandemic policy failures.

This however unfortunately means that more of the burden of fighting inflation this cycle has to fall on the household sector.

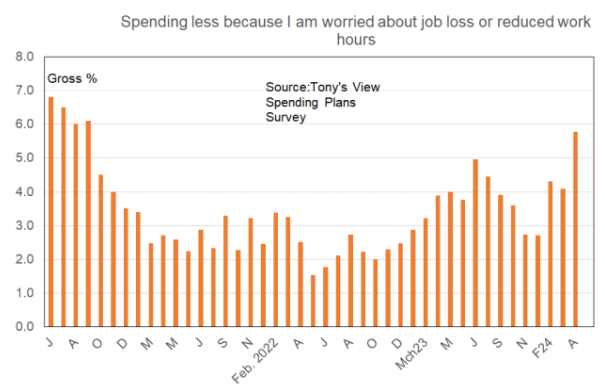

I can tell from my monthly surveys that people are highly and increasingly aware of the weak state of the labour market.

For instance, my monthly survey of real estate agents sponsored by NZHL shows that whereas in January only 14% of agents said buyers were worried about their employment, now a record 50% say that.

And from my monthly Spending Plans Survey the proportion of people saying they are cutting back spending because of job worries has risen to 5.8% from 2.7% at the start of the year.

We can see that there is labour market weakness underway, and we know this is an important conduit for tight monetary policy to reduce inflation.

It does so by making people scared of spending or unable to spend because they have lost their income, and by suppressing wages growth.

So, is wages growth slowing down at a pace which will please the Reserve Bank? Let’s see.

Average hourly ordinary time earnings grew by 0.3% in the March quarter after rising 1.1% in the December quarter, 2.2% in the September quarter, and 1.9% in the March quarter of 2023.

In fact, in March quarter 2022 the rise was 1.6%, 2021 0.6%, 2020 0.9%, 2019 0.5%, and 2018 0.7%. The latest quarterly rise is the lowest for this quarter since 2015. This is a positive development with implications for inflation and monetary policy.

The annual rate of wages growth has fallen to 5.2% from 6.9% last quarter and 7.6% a year ago. This is still well above the average rate of growth consistent with inflation averaging just above 2% of about 3.3%. But the direction of travel is clear.

There is now no jobs growth in the New Zealand economy and wages growth is slowing.

Monetary policy is definitely working and there is just one element needing to fall into place to allow the Reserve Bank to start cutting interest rates. Businesses need to cut back on their price rise plans.

Unfortunately that has yet to happen and that means no cut in the official cash rate until late this year at the earliest.